After I posted photos from Saturday’s Chiefs vs. Dolphins sub-zero NFL playoff game, I received a lot of messages. Some were from people asking how I was able to stay warm, and the rest were from photographers who all asked the same question: “How did you keep your hands warm?” Short answer? I wasn’t able to keep my fingers warm, but I was able to maintain feeling in them.

The longer answer is all about managing the cold. How did I survive photographing the coldest game at Arrowhead Stadium, and the fourth coldest ever for the NFL? First I’ll explain my clothing choices, then get into the photography.

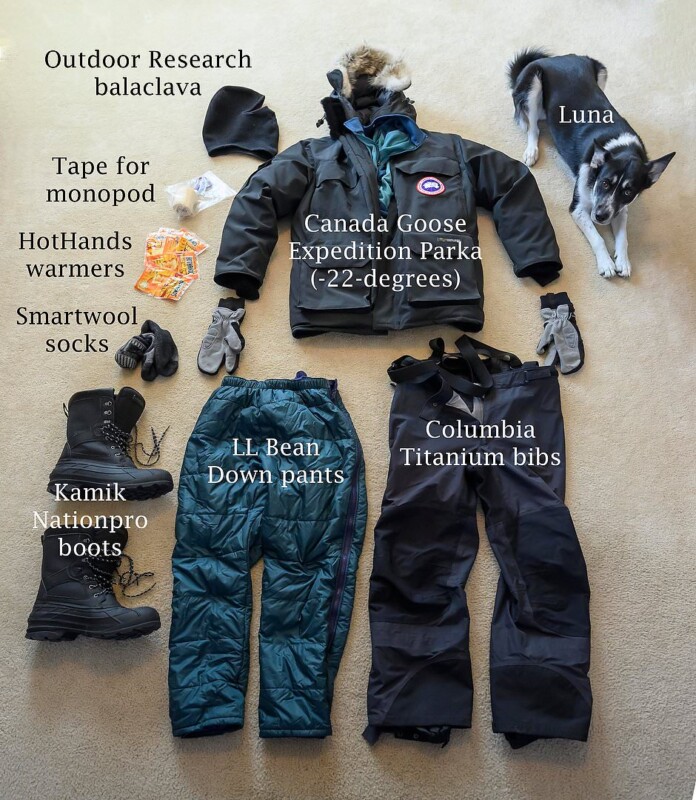

Clothing

When it comes to dressing for low temperatures, there’s one cold, undeniable fact – insulation equals warmth. And that means bulk. There’s no magic material that’s thin and will keep you warmer than something with thickness to it. That’s a lesson I learned as a newspaper photographer in upstate New York, where I had to spend a lot of time outside in cold, snowy weather.

Most days from mid-December to March, I’d go to work in boots, heavy pants over long underwear, a turtleneck under a sweater topped by a heavy coat, plus a hat and something on my hands. The problem is, if you want to keep your fingers warm, you can’t beat a thick mitten. As a photographer, though, you can’t do that: you need your fingers to use the controls on the camera. So, for the twenty years I worked there, I tried every glove or mitten combination known to man.

For a while, the best solution I found was thin liners under “half-finger” mittens, where I could pull back part of the mitten to expose my fingertips. That worked okay, but if my fingers were out of the mitten for more than a few seconds at a time, they’d quickly start losing feeling. And, of course, constantly covering and uncovering the finger was a hassle. Then I discovered a special type of cross-country ski glove while covering a competition in Colorado,

One of the variations in that sport is Biathlon. You’ll see it at the Winter Olympics, where athletes race a course that doesn’t involve just skiing, but also stopping at regular intervals to shoot at a target. A glove was developed for that use which was a cross between a mitten and a glove. There’s a thumb, a mitten area for three fingers, and a separate part for the index finger between them. That allowed the athletes to handle and shoot a gun but prevented freezing the rest of their fingers. As soon as I saw them I bought a pair, and have been happily using them for over ten years. However, while they’re good, they’re not perfect.

Remember that part about “insulation equals warmth?” And “there’s no magic material?” All of that still applies. Those cross-country ski gloves are the best solution I’ve found, but I know that my fingers will still get cold if the temperature drops below a certain point. That’s a fact I’ve learned to accept if I want to be able to shoot pictures. The key is that they don’t get so cold that I lose feeling. If temps drop below 30 Fahrenheit, I add small chemical hand-warmers to the gloves. One of those can fit easily into the mitten part, so when I’m not shooting I can pull my thumb and index finger into that space to warm them up a bit. For the below-zero conditions Saturday night at the Chiefs game, I also taped a larger heat pack to the top of my hand. Of course, if the rest of me is freezing, keeping my hands functional won’t matter as much.

For cold weather, layers are the key. With layers, if you get hot, you can shed some clothing. Why is getting hot bad? Sweat. If you start perspiring, that moisture will cool you down, and force your body to expend more energy trying to keep you warm. That’s also why your base layer (closest to your skin) has to be synthetic, not cotton. Cotton, once wet, takes much longer to dry. In the outdoors world, they say, “cotton kills,” because of that (it can lead to hypothermia). Synthetic materials not only dry much faster but can wick perspiration away from your skin.

On top of that base layer comes the insulation. It can be one or multiple pieces, depending on how cold it is and your personal preference. Down-filled clothing is the lightest, as it creates that needed bulk without being heavy. But you have to be careful to keep it dry. Once wet, down clumps and no longer insulates, plus takes a long time to dry (there are synthetic down alternatives that can still function after getting wet, though nothing beats down for pure insulating value). Then over that middle layer(s), add a “shell,” a top layer to repel wind, water, or snow. In this case, my expedition parka is both the thick down layer as well as the tough outer layer.

Keeping your feet warm is also important, and follows the same rules as above – it’s all about insulation. You need enough under your feet that the cold surface you’re standing on doesn’t radiate up into the bottom of your feet, and enough surrounding those feet as well. For socks, what I said about cotton and sweat applies to your feet too. Synthetic, wool, or a combination of the two are what you should be wearing. While I haven’t had much success with chemical heat-pack insoles, I put a pair in just before kickoff on Saturday, and they added some warmth for about 30 minutes. Also important is that you don’t pack your feet into the boots too tightly. Compress all that insulation and you’ll defeat (de-feet – hah!) its purpose.

For the head, a simple stocking cap or hood probably won’t be enough. The more of your face you can have covered, as well as your neck, the warmer you’ll be. Saturday night, many photographers, as well as players, were wearing balaclavas, which are great for that (and no, they’re not the same as the Greek baklava dessert!). Be mindful that if you cover your mouth and nose, your breath will probably fog your viewfinder and/or glasses. And my balaclava, warm as it is, was no match for Saturday night’s cold and wind. I needed the fur-lined hood of my parka, or the cold became painful.

What else can you do? As far as hands go, the gloves and heat packs I mentioned above are a good start, but anything you can do to keep them out of the wind will help too. I’ll stuff them in my pockets at times, or even wear a “muff” around my waist like quarterbacks use that I can slip my hands into during breaks in play (and there are heat packs in there as well).

Photography

Extreme cold weather brings challenges for camera gear too, and part of that is how it might change what you carry. In my job covering Chiefs home games for Associated Press Images, the priorities are isolated player action photos, tight action shots, and a variety of special requests from the NFL. Normally I’ll bring up to three camera bodies and five lenses.

Knowing I wouldn’t be able to easily change lenses, and carrying about ten added pounds in clothing and boots, I took less to Saturday night’s game. Two Nikon Z 9 bodies, the Nikkor Z 400mm f/2.8 TC lens (I can flip a switch to drop in the 1.4X teleconverter, making it a 560mm f/4 lens), the Nikkor Z 70-200mm f/2.8 lens with 1.4x teleconverter (resulting in 105-300mm at f/4) and the Nikkor Z 24-200mm f/4-6.3 lens. For pre-game, I’d use the 400mm and 24-200mm, then during the game the 70-200mm with converter instead of the 24-200mm. In the closing minutes, I’d replace the 70-200mm with the 24-200mm for after-game photos. I’d carry the camera with the 400mm on a monopod and the second camera on a cross-body strap.

There’s a heated photo room for photographers to work out of, where we can download, edit, and transmit our photos. However, to help avoid condensation that can happen when going from very cold to warm spaces (outside/inside), for this game, most of us left our cameras in the unheated tunnel outside that room when going inside to edit.

The extreme cold also had an impact on the photos we could make and where we could shoot from. Steam coming out of players’ mouths could look cool unless it obscured their faces. Worse, with all the heaters for the teams on the sidelines, the resulting heat waves made it nearly impossible to shoot into the bench area. Those heat waves were even radiating out onto the field at times, creating additional issues. Normally I’ll work up and down both sidelines as well as shooting from the end zones, but this game I spent more time in the end zones. That was because of those heat waves, and also because running around with all the heavy clothing and boots was more exhausting. During most games, I’ll walk 5-6 miles, but this game I did just under 4, and at the end was more worn out than usual.

As for batteries, an old friend of mine answered that question once by saying, “I find photographers get exhausted by the cold faster than today’s batteries.” That’s pretty close to the truth. Not surprisingly, the larger the battery, the longer it will last. Those Nikon Z 9’s have big (3300mAh/36Wh) lithium-ion batteries, and my primary camera was down to 29% at the end of the night, the other body to just 50%. That performance is similar to what I’ve had in warmer weather. Between the two, I shot just over 2100 frames (RAW files) over the course of the evening. While I had two spare batteries with me, I didn’t need either. On the other hand, friends shooting cameras with smaller bodies that use smaller batteries (mostly Sony) were regularly changing batteries (lower mAh and less than half the Wh), and recharging when they had time. Of course, many of them were transmitting from their cameras on the field, which would also use more power. As always, there are advantages/disadvantages to both larger and smaller camera bodies.

When your fingers get cold and start to lose feeling, finding that shutter button through gloves can be difficult at times. This is a problem I ran into while shooting skiing in Colorado years ago. The solution was an accessory called the ProDot Shutter Button Upgrade. They come two to a pack, and they’re just small red rubber buttons, textured on top, that you stick to your shutter button. With one attached, I have no problem finding that shutter button, even when my fingers start to go numb. They won’t stay on forever, but I’ve had them last through multiple days of ski photography and used them again Saturday night.

Finally, I cut back on the amount of time I spent outside during pre-game activities. Normally I’ll walk out there about 2.5 hours before the game, as some players come out to warm up (not in uniform). After shooting that, I’ll head back inside, download, and send some photos. Then an hour before kickoff, both teams return to the field in full uniform for drills for about 30 minutes. After a quick trip inside again to download and send more photos, I’ll go right back outside to get in position and wait for introductions. This time, to avoid getting too cold before the game ever started, I did about half of all that (although still sent 14 photos before the start).

Thankfully, when the game ended most of the Dolphins ran straight to the locker room. A few stayed out to visit old friends among the Chiefs, and there were the obligatory on-field interviews. By the time I left the field, the temperature was now at minus-9, with a wind chill around 30-below. I downloaded, edited, captioned, and sent about 40 more photos before packing up and heading home, transmitting more photos the following morning. A long, cold day, but I’ll call it a success. Any time you finish something like that, make the photos you need to, and have all your fingers and toes intact, it’s a win.

The Chiefs won too, and have now advanced to next Sunday’s playoff game. But this one will be in Buffalo against the Bills. And the forecast in Buffalo that day is downright balmy, with a high of 25 degrees. Ah, to be working in warmer weather!

About the author: Reed Hoffmann is a photographer and photography instructor who has been in the photo industry for decades and who has used every Nikon DSLR (and taught most of them). The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Follow along with Hoffmann’s latest workshops here. You can also find more of Hoffmann’s work and writing on his website, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. This article was also published here.