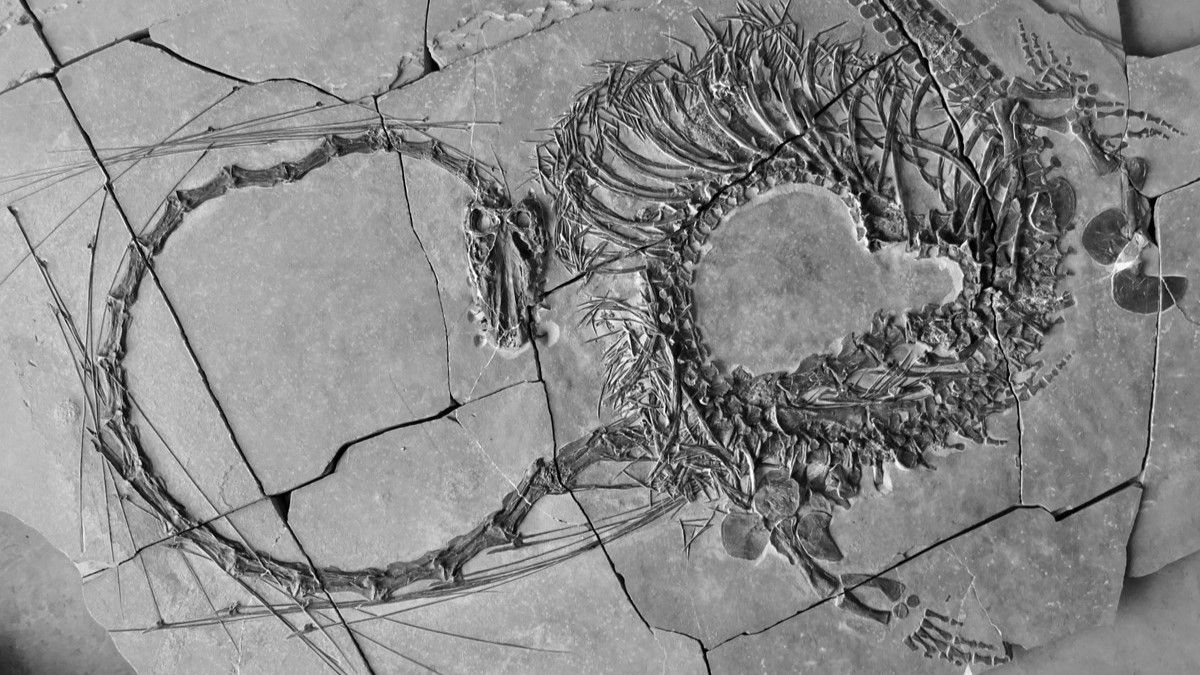

Scientists have unveiled stunning fossils of an ancient seaborne “dragon” discovered in China.

The 240 million-year-old animal — nicknamed the “Chinese dragon” — belongs to the species Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, a reptile that used its remarkably long neck to ambush unsuspecting prey in shallow waters during the Triassic period (252 million to 201 million years ago).

The species was first found in limestone deposits in southern China in 2003, but scientists have now pieced together remains to reconstruct the full 16.8-foot (5 meters) span of the spectacular ancient carnivore for the first time.

The researchers revealed the new findings in a study published Feb. 23 in the journal Earth and Environmental Science: Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

“It is yet one more example of the weird and wonderful world of the Triassic that continues to baffle paleontologists,” Nick Fraser, keeper of natural sciences at National Museums Scotland said in a statement. “We are certain that it will capture imaginations across the globe due to its striking appearance, reminiscent of the long and snake-like, mythical Chinese Dragon.”

The fossil reveals some of the ancient sea dragon’s striking features.

Related: 10 jaw-dropping dinosaur fossils unearthed in 2023

First and foremost is its neck, which stretches nearly 7.7 feet (2.3 meters) and contains 32 separate vertebrae — in comparison, giraffes (as well as humans) have only seven neck vertebrae.

The snake-like shape of the dragon’s articulable neck likely gave it a remarkable ability to sneak up on its prey, which it did after maneuvering into position with its flippered limbs. Some of the fish snared in the dragon’s serrated teeth are still preserved inside the sea monster’s belly.

The researchers note that though the strange creature may be reminiscent of the Loch Ness Monster, it is not closely related to the long-necked plesiosaurs that inspired the famous mythical creature.

“We hope that our future research will help us understand more about the evolution of this group of animals, and particularly how the elongate neck functioned,” first-author Stephan Spiekman, a postdoctoral researcher based at the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History, said in the statement.