Introduced at the beginning of the 20th century, autochromes were the very first form of color photography until it was comprehensively replaced by film in the mid-1900s. In 2024, just one man perseveres with the autochrome process.

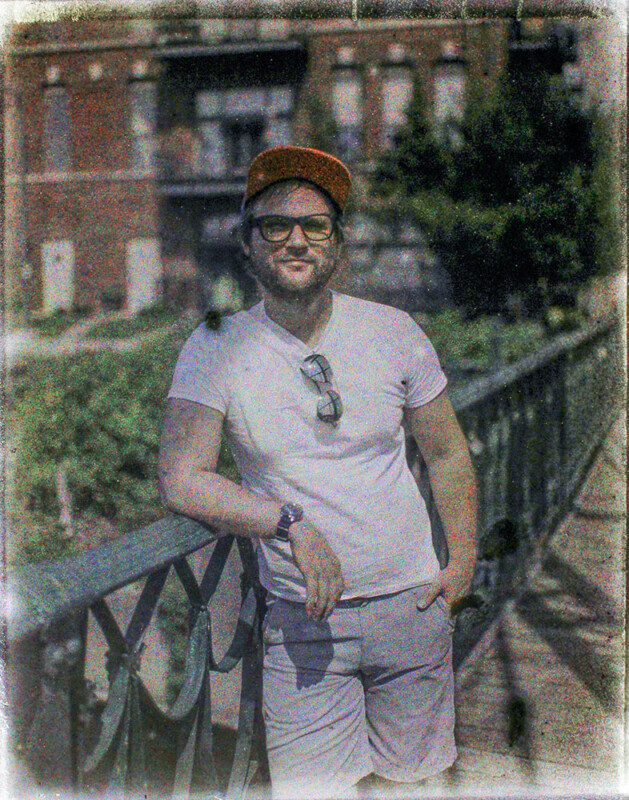

At least that’s what analog photographer Jon Hilty believes — and it’s understandable given the intricate and time-consuming nature of carefully painting colored starch grains onto an autochrome plate, but he tells PetaPixel that it’s all worth it when a photo comes out nicely.

“It’s extremely satisfying,” Hilty says. “Especially the ones that turn out really well. I love going back and just looking at them.”

![]()

By trade, Hilty is a control engineer so it is perhaps no surprise that he enjoys a technical challenge such as making photographs from scratch; he previously experimented with daguerreotypes, wet plate collodions, and cameras made out of potatoes.

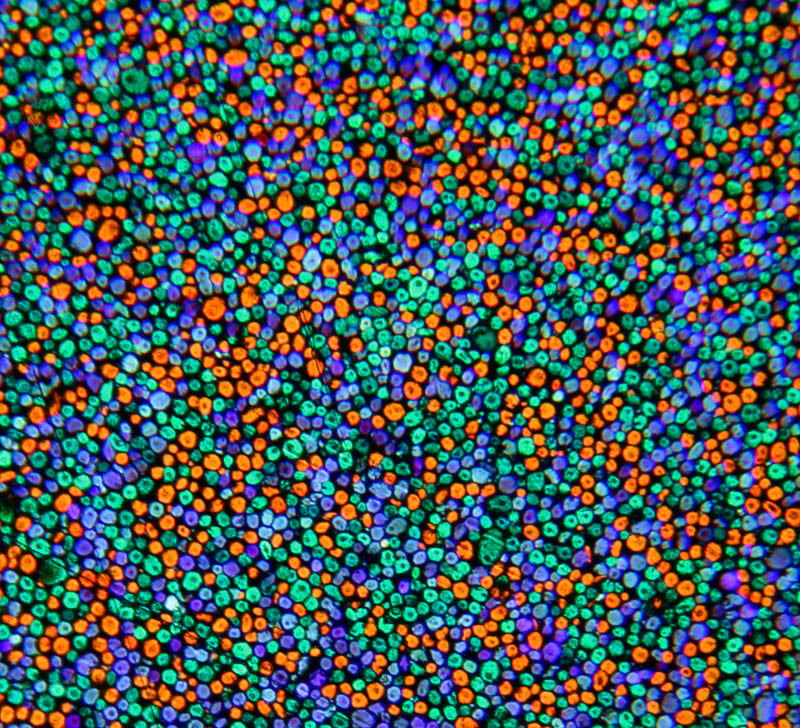

It takes Hilty a week to make a batch of autochrome plates which are made via a series of layers on a glass plate.

“The first varnish is almost like a rubber cement, like a sticky rubber layer that you can apply to the glass which remains sticky after it dies,” the Michigan native explains.

“Then you can put the starch on it which is all mixed together and you sort of brush it around and it will stick to the plate.”

The aim is to get a thin layer of red, blue, and green-colored starch particles flat on the plate, but this is one of the most challenging parts of the process because if you don’t flatten it there is “interstitial” space between the particles which produces a darker image.

Hilty has purchased computer numerical control (CNC) machines to aid with the flattening and has a custom-made coding head which by itself cost over $2,000.

“A lot of the stuff was an upfront cost. But now that I’ve gotten that equipment the cost isn’t too bad. It can be pretty sustainable now,” he adds.

![]()

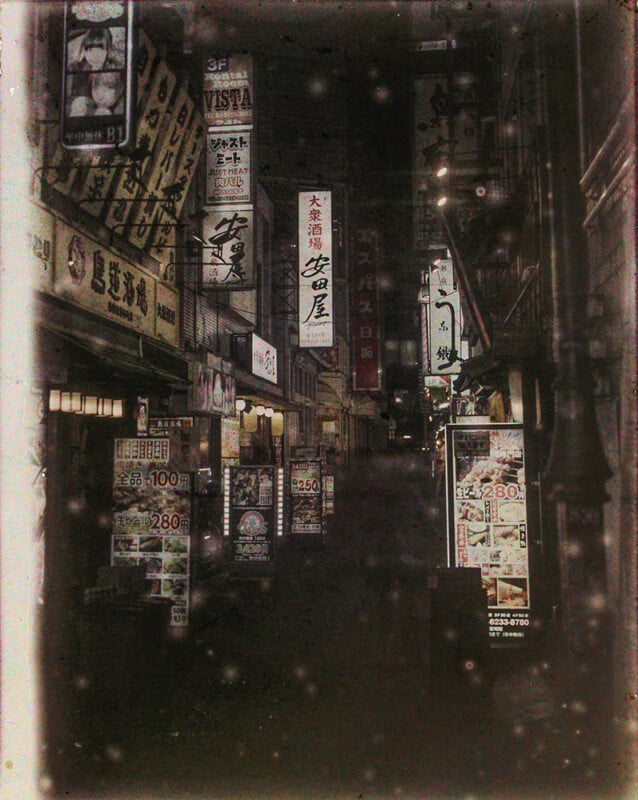

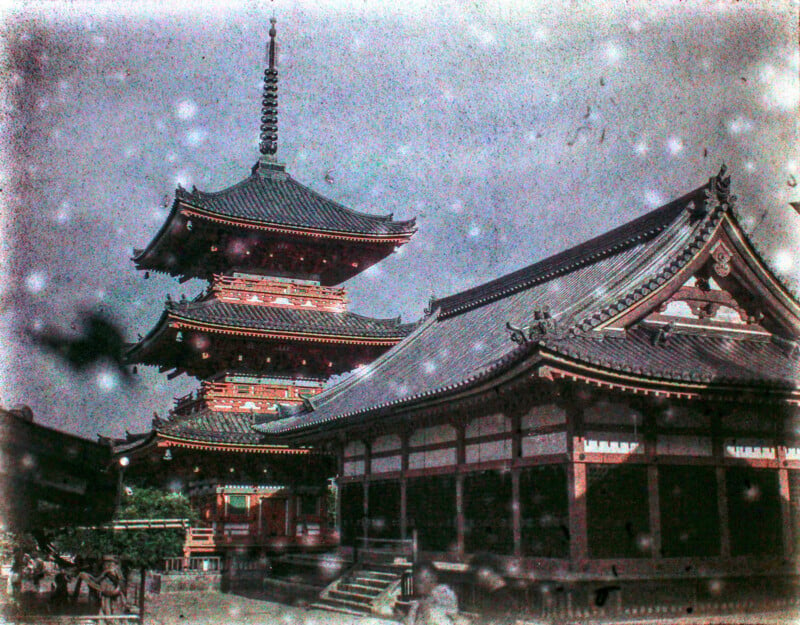

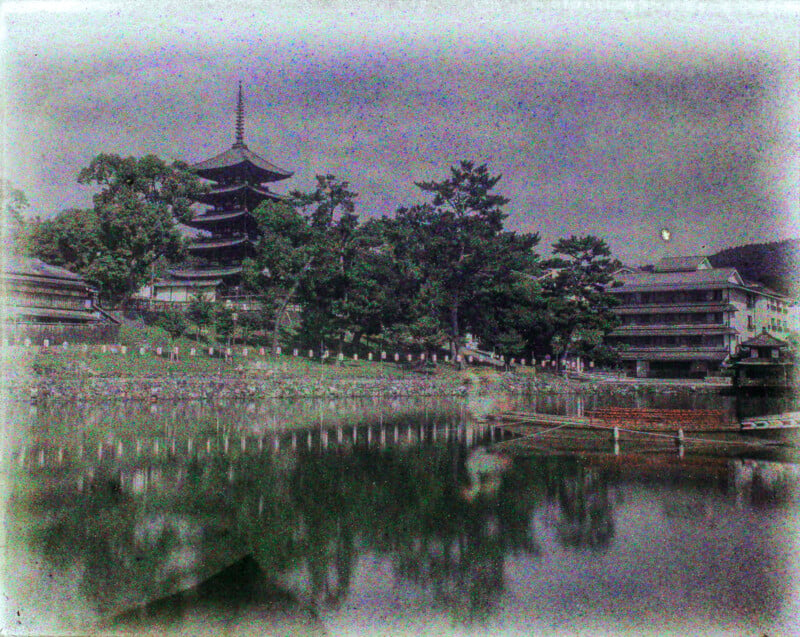

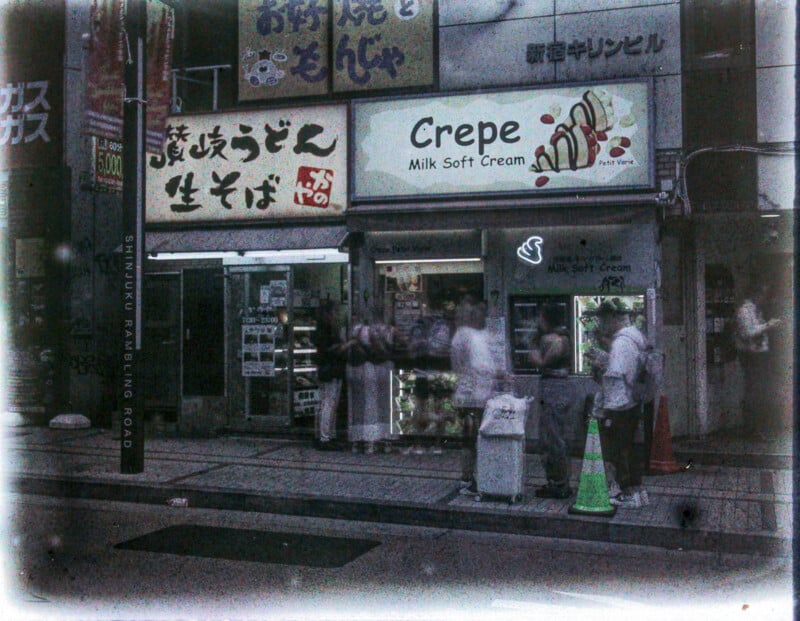

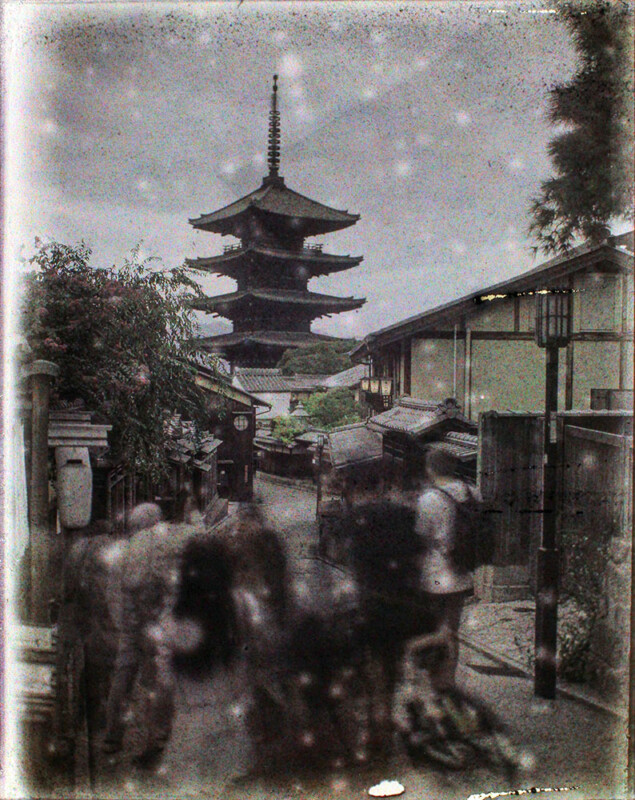

Shooting Autochromes in Japan

Hilty says he “went crazy” over a period of two months preparing 48 plates for his trip to Japan. He used finer grains by borrowing a method from the Lumière brothers — who patented the autochrome in 1903 — that involved separating the finer starch particles from the larger ones before dyeing them. He was able to get his exposure times down to “about one second” when shooting in bright sunlight

But Hilty, who works with computers and robots, admits to taking a “technical approach” when shooting the autochrome plates on his Shen Hao 4×5 camera.

“A lot of times I’ve joked about trying to shake the engineer’s brain. Sometimes a plate might come out and it might look really cool, but it’s not the way that the scene looked and that’ll bother me. And it’s hard getting past that sometimes.”

It’s hard to know exactly what ISO speed the plates are, Hilty thinks the best he could possibly achieve is ISO 80 but there are all manner of technical problems preventing him from making a faster emulsion.

Beacon of the Autochrome World

Hilty says he is aware of “quite a few people” who are also working toward making their own autochromes and hopes that other people join him in the novel photography space. When PetaPixel suggests he is a beacon of the autochrome community he humbly agrees.

“With a lot of the [photographic] processes that I’ve done in the past, I’ve had an idea, a mental image of the things that I wanted to do with the process and once I’ve accomplished that, I wasn’t very interested in doing it anymore,” he says.

“The autochrome process is so difficult to do that. My plates still have flaws, I can do them better, and I can make them faster. They still have issues with delaminating a bit after a year. So it’s stuff like that that’s still fun for me to experiment and learn about.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

More of Hilty’s work can be found on his Instagram and website.

Image credits: Photographs by Jon Hilty.