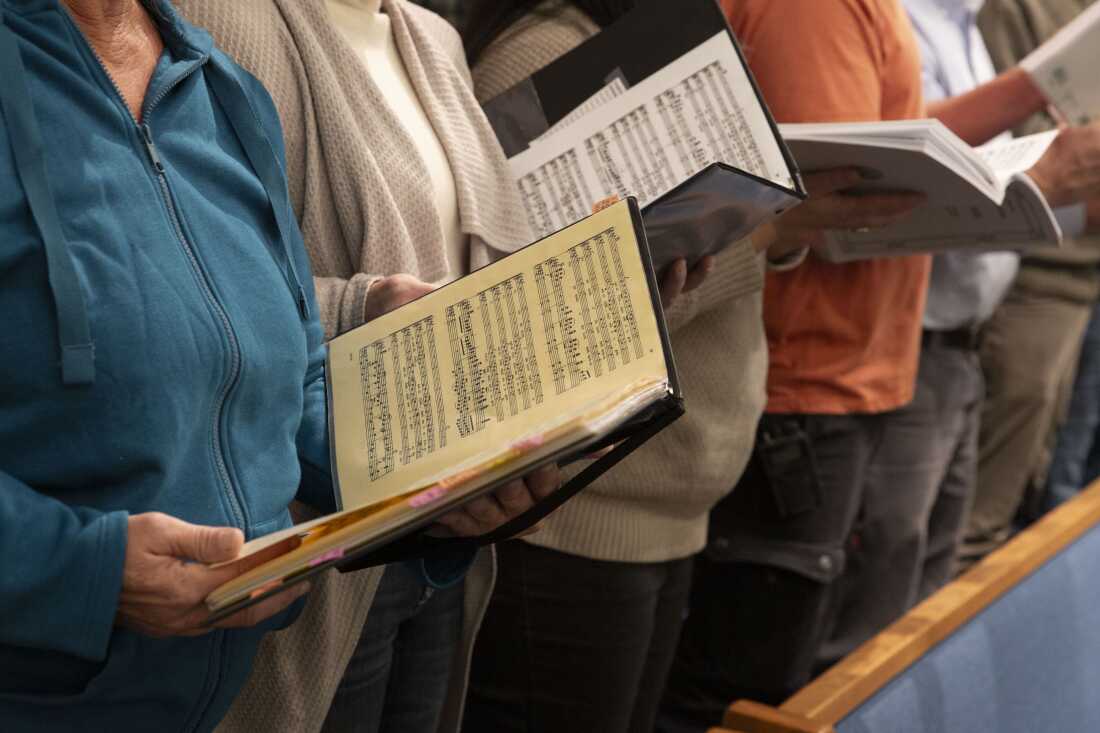

The North Fork Community Choir practices at the North Fork Baptist Church in Paonia, Colo., on Nov. 6 — the day after Election Day.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

Over the last few years and through this year’s contentious campaign season, which was rooted in America’s deep divisions, there has been a coarsening in the way people talk to each other. We wanted to explore how some are trying to bridge divides. We asked our reporters across the NPR Network to look for examples of people working through their differences. We’re sharing those stories in our series Seeking Common Ground.

PAONIA, Colo. — On a Wednesday night at a spacious, contemporary-looking church on the edge of Paonia, a small town in western Colorado, the 40 or so members of the North Fork Community Choir ran through their regular warmups.

“Really pay attention to that ‘E’ vowel,” said music director Stephanie Helleckson, as she guided the singers through various scales and arpeggios from behind a music stand. “See if you can make that a little bit rounder as a group.”

Helleckson listened carefully to how the singers’ voices blend; the details matter in an art form that’s all about achieving harmony.

Helleckson, who comes from a musical family and has spent most of her life in Paonia, said harmony is important — not just musically, but also socially.

“Because we’re all coming from different backgrounds and different perspectives, and we’re coming together to do something together, we have to learn how to not agree with somebody, but still work with them,” said the vivacious and businesslike music director.

A view of Paonia, Colo., and the surrounding West Elk Mountains.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

The North Fork Community Choir is based in a part of the country where the politics are all over the map.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

Paonia has farming and ranching families, artists, winemakers, remote workers — and a mix of political views, one choir member says.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

The North Fork is an ideologically diverse community

Cooperation is not a given, since the North Fork Community Choir is based in a part of the country where the politics are all over the map. The singers have had to come up with creative ways to continue to sing in harmony.

“We’ve got people from pretty far right to pretty far left in the chorus,” said choir member Jan Tuin.

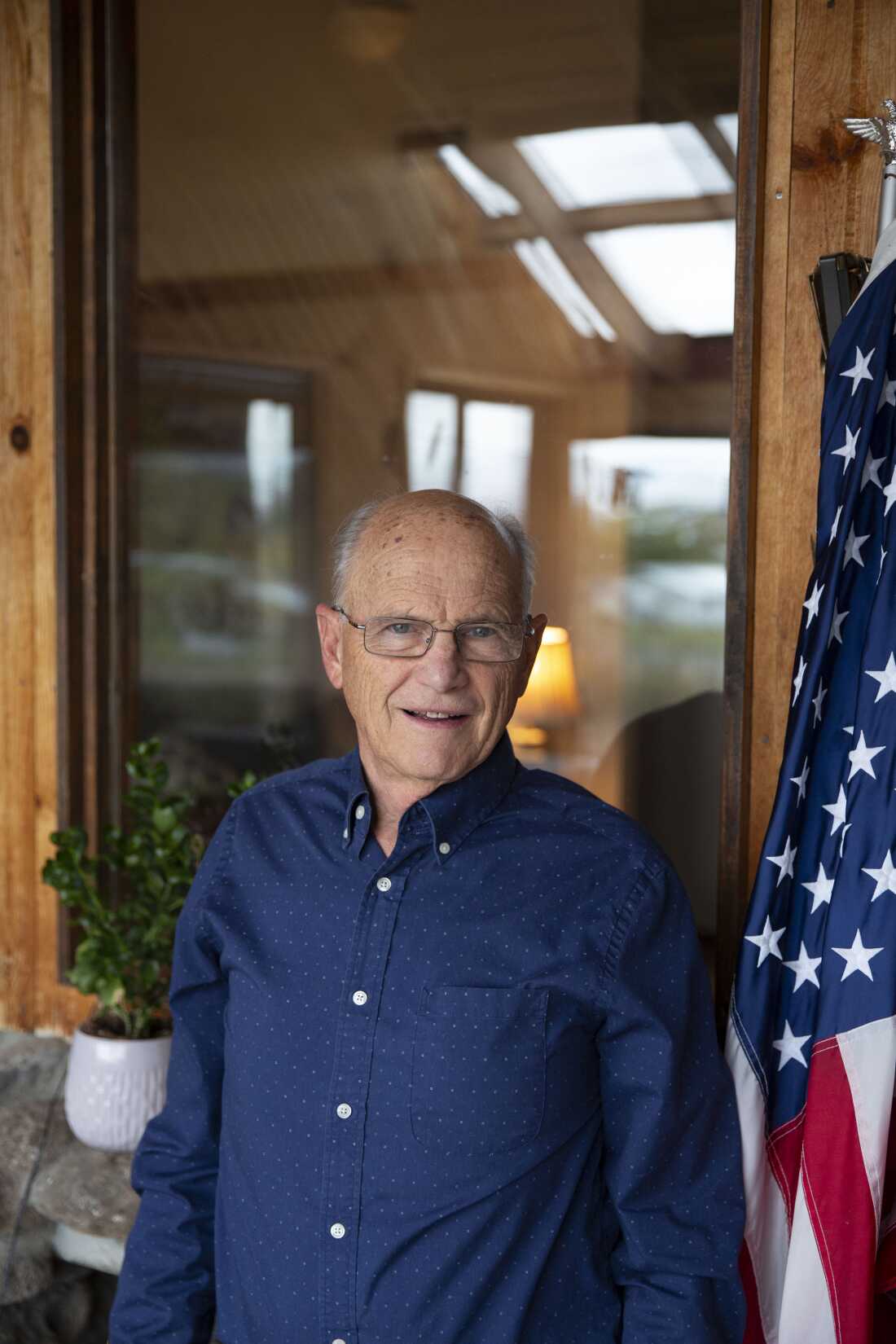

Tuin has been living in the area since 1964. He said his dad, an auto body repairman, moved the family from near Denver in search of a slower pace of life. Over coffee at Paonia Books, a hip, newish bookstore and cafe in downtown Paonia, Tuin said the mining, farming and ranching families who’ve been around for generations have in recent decades been joined by an influx of artists, winemakers and remote workers in fields like tech.

Choir member Jan Tuin, who helped found the first community singing group in the area, at his home in Hotchkiss, Colo.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

“And so the people here now are much more diverse, I would say,” Tuin said.

Nearly everyone in the choir is white, reflecting the area’s racial demographics. But the members range in age from 11 to 87. Some of the singers believe in God; others do not. Some own guns; others do not. When the choir required masks and/or vaccines for rehearsals at various points during the COVID-19 pandemic in accordance with federal recommendations, some were happy to comply. But at least one member quit.

Tuin said people avoid bringing up potentially controversial topics during rehearsal. “We talk about our gardens a lot,” he said, laughing.

No matter their politics and values, all of the 20 or so singers NPR spoke with for this story said they focus on music-making as a uniting force and as a way to at least temporarily forget differences. This includes choir members Mary Bachran, the recently retired mayor of blue-leaning Paonia (“We make harmonies together. It’s just so wonderful.”) and Chris Johnson, the recently appointed mayor of red-leaning Crawford, a nearby ranching community. (“We’re just all there to sing.”)

Mary Bachran, community choir member and former mayor, in downtown Paonia, Colo.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

Everything’s not good in “America”

Yet the music itself sometimes draws the differences out.

The choir’s Broadway program back in the spring is a case in point. It involved medleys from well-known musicals such as My Fair Lady, Rent, Pippin, Dear Evan Hansen — and West Side Story.

The song “America” from the latter, which premiered in 1957, might be one of the most famous in the American musical canon. But some of the lyrics describing Puerto Rico as an “ugly island” rife with disease and poverty did not sit well with singers like Ellie Roberts.

“I really struggled with that because it sort of implies that Puerto Rico stinks and why wouldn’t they leave?” Roberts said. “And it just sort of encouraged some of those stereotypes.”

Roberts, a local schoolteacher, said the chorus discussed the issue at rehearsal. “What are we celebrating and what do we not want to celebrate?” she said.

They thought about changing the lyrics, but ended up doing the song with a disclaimer that music director Helleckson made from the stage.

“You have to think about context for this piece,” Helleckson said in a video of the performance captured in May. “This piece has some things that are maybe not as acceptable in today’s day and age as they were when it first came out.”

The North Fork Community Choir practices at the North Fork Baptist Church in Paonia, Colo.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

Music director Stephanie Helleckson, who has spent most of her life in Paonia, leads community choir practice at the church.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

During community choir practice at the North Fork Baptist Church in Paonia.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

“Master of the House” an issue too

Meanwhile, other members of the ensemble brought up a different concern to do with the raucous showstopper from Les Misérables, “Master of the House.”

In the song, a seedy innkeeper and his entourage of petty criminals invoke Jesus as they fleece their customers.

“It bothered me, because I did not want to use the Lord’s name that way,” said singer Kim Johnson, a Christian counselor. Johnson said she and some others from the group discussed the matter with Helleckson and came up with alternatives to singing “Jesus.”

“I sang ‘cheeses’ instead of ‘Jesus,'” said Johnson. “It worked.”

Pushing boundaries to launch conversations

Helleckson said she knew the Broadway program would be a little bit provocative.

“It’s pushing boundaries that some people are not comfortable with in our little rural pocket of America,” Helleckson said. “And so part of programming some of this music is to actually have those conversations. So we don’t just assume that everybody’s the same as us and everybody believes the same things and acts the same way.”

According to a Chorus America report assessing the impact of group singing, choir members are more adaptable and tolerant of others than the general population. “Almost two-thirds of singers (63%) believe participating in a chorus has made them more open to and accepting of people who are different from them or hold different views,” the study noted.

New York University sociology professor Eric Klinenberg said the mere act of coming together to undertake a regular, shared activity with others, such as choral singing, can promote bridge-building. But it’s possible for such groups to go further.

“If your objective is to just get a group of people together to sing well, forget about everything else in the world, maybe you don’t need to encourage those other conversations about politics,” said Klinenberg, who studies how people gather and connect both within and across ideological lines.

But, he said, if the objective is also to create a more decent society and bridge differences by using the relationships that you build while making music together as a foundation of trust to advance a conversation about something like politics, “that could be an amazing thing.”

Choir member Chris Johnson, the recently appointed mayor of Crawford, Colo., says: “We’re just all there to sing.”

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

Choir members hug at practice the day after Election Day.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

Small steps toward greater understanding

In a small way, the issues that arose with the Broadway concert point toward this aspiration. Choir member Chris Johnson, for example, said he didn’t have a problem with West Side Story. But he doesn’t fault those who pushed for the disclaimer.

“I don’t think that explanation was necessary, but it’s OK,” he said.

And singer Linda Talbott said her mind has been expanded as a result of the faith-based objections other singers in the group had to Les Mis.

“I think I’m much more aware now of what could be objectionable to certain people,” she said. “I don’t think I thought about it. There it was in front of me, I wanted to sing it, and I did.”

Helleckson said she would like to continue to program more material that inspires these types of conversations.

The North Fork Community Choir has been prepping for upcoming holiday performances.

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Luna Anna Archey for NPR

In the meantime, the ensemble is prepping for a pair of holiday performances of Handel’s Messiah. The singers said the music is challenging. But so far it’s not been too controversial.