New Delhi: Attitudinal obstacles remain a significant challenge for the disabled individuals even as there have been efforts from the government and society, says Dr. Satendra Singh, a relentless disability-rights advocate.

Dr Singh emphasises that the issue of accessibility extends far beyond medical students or doctors. “It’s surprising—and disheartening—that hospitals, of all places, are not disabled-friendly,” he tells ThePrint on the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, which is observed on 3rd December every year.

“It’s not just about physical spaces. Hospital websites, for instance, must be inclusive.”

According to the 2011 Census, 2.12 percent (26.8 million) of India’s population are disabled of which 56 percent are males and the remaining 44 percent females.

The physiology professor at the University College of Medical Sciences (UCMS) and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital in Delhi highlights the importance of universal design in healthcare facilities, noting that accessibility benefits more than just persons with disabilities.

“Accessible premises in medical colleges and hospitals also support people with chronic illnesses, pregnant individuals, the elderly, children, and even those of shorter stature. It’s about creating spaces where no one has to face unnecessary barriers,” he explains, underscoring his vision for universal inclusivity in healthcare settings.

For this purpose, he advocates for a collective effort, urging private players, the government, and society to unite in fostering inclusivity.

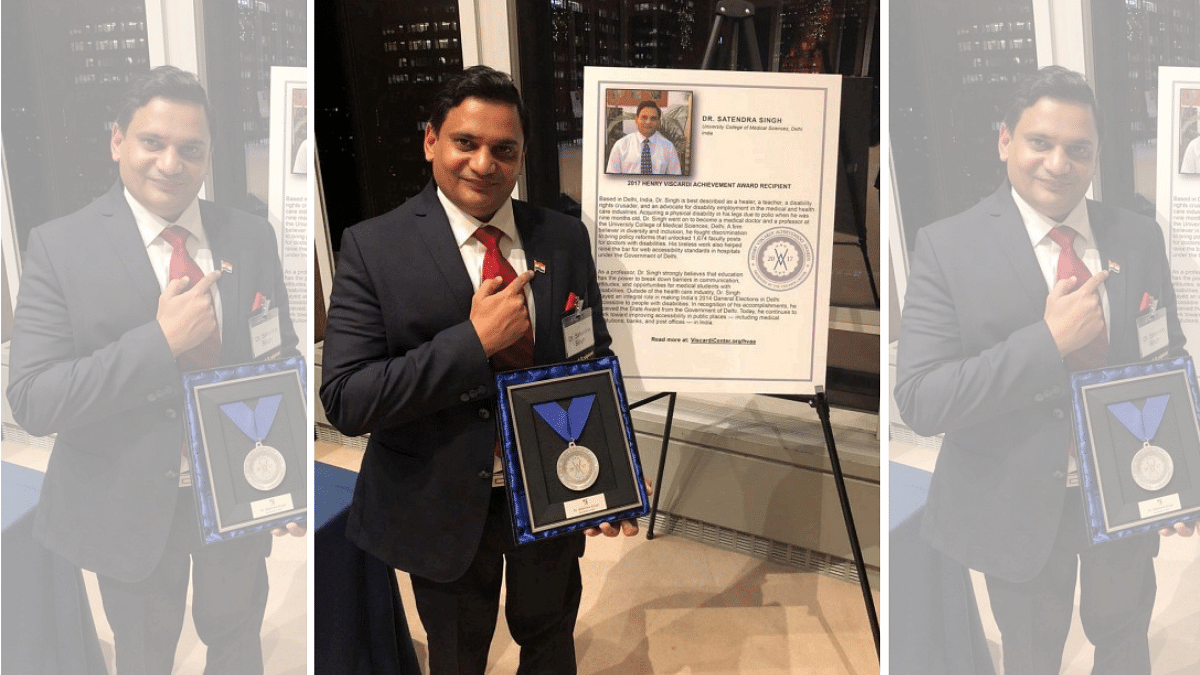

A polio survivor since infancy, Singh has been on a mission in the fight for inclusivity in India’s medical field. He is the first Indian recipient of the Henry Viscardi Achievement Award in 2017, and was also honoured with the National Award by the President on the National Voters’ Day in 2021.

It was Singh’s petition to the court of the Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment that prompted the central government to instruct the erstwhile Medical Council of India to mandate inclusivity for disabled doctors across all medical institutions.

Further, his Right to Information (RTI) application revealed that doctors with disabilities were deemed ineligible for specialist CHS (Central Health Services) posts in teaching, non-teaching, and public health specialties.

Persisting through a four-year battle, he lodged complaints and appealed to the health ministry to rectify the discriminatory policies. His relentless efforts ultimately led to the opening of 1,674 specialist central posts for eligible disabled doctors in 2015.

With today’s blind and visually impaired individuals relying on apps and assistive technologies rather than Braille, he says, it’s vital for hospital services—such as OPD registrations and diagnostic requests—to be accessible to those with low vision, epilepsy, or other conditions.

Dr Singh also dwelled on the lack of inclusivity in diagnostic equipment. “Most hospitals don’t provide height-adjustable examination tables, which are essential not just for people with disabilities but also for the elderly, those with chronic illnesses, individuals with obesity, or people of shorter stature,” he says.

Similarly, equipment like mammography systems and MRIs are rigidly designed, excluding individuals with diverse needs.

Even the design of life-saving medicine bottles poses significant challenges, he says while presenting the example of how people with rheumatoid arthritis struggle to open these bottles. Similarly, for the blind, all medicine bottles look the same, making them dependent on others to identify them.

The absence of QR codes on bottles makes it tougher for individuals with visual impairments to use such technology for identification, he adds.

Singh argues that including health professionals with disabilities in policy-making teams is essential to address these gaps and create truly inclusive healthcare environments. “Policymakers often overlook these small yet impactful changes,” he asserts.

Also Read: Over a year since RML’s transgender OPD opened, a sex reassignment surgery is yet to take place

AI challenge

While acknowledging the growing awareness of disability issues due to social media, he highlights a new challenge: artificial intelligence (AI). “AI systems rely on data, but we lack disaggregated data on disability in India.”

Able-bodied individuals often collect and design this data, unintentionally embedding ableist biases due to a lack of lived experiences, he says. “AI systems need to account for the specific needs of people with disabilities. This requires researchers with disabilities to be involved in data collection and design to ensure sensitivity and inclusivity,” he explains.

To address this area, he calls for “data justice” to ensure that the disability community is accurately represented and that the AI systems serve their needs effectively.

In this aspect, Dr Singh is critical of the policymakers for the removal of critical disability-related questions from the NHS data survey, despite legal mandates under the Disability Act to collect such data. “We made multiple representations to the government, but key questions were excluded. This undermines accountability,” he says.

Changes in medical education system

In their research paper, ‘One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: Urgent Priorities to Embed Disability and Queer Health in Medical Education Systems,’ co-authors Singh, Rohin Bhatt, and Mohammed Ahmed Rashid emphasise the need for medical education systems to integrate disability and queer health awareness.

They argue that medical curricula should include a comprehensive understanding of disability, as defined by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and recognise the difference between medical and social models of disability.

On his personal level, Dr Singh established an Enabling Unit for persons with disabilities and founded Infinite Ability, a special interest group focused on disability within the Medical Humanities Group at UCMS, University of Delhi. The group aims to promote and coordinate efforts among medical professionals with disabilities, fostering a collaborative approach to integrating medical humanitarian practices.

“Our focus should not be on eliminating disability. Disability will always exist,” he says. “What we need to focus on is strengthening our support systems, making them robust and streamlined, so that individuals, whether they have sickle cell disease, leprosy, or any other condition, are gently integrated into society.”

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: In Delhi hospitals, thalassemia patients suffer as life-saving Desferal scarce, set to become 50% costlier