GLOFs occur when lakes formed by melting glaciers suddenly burst open. They have been a threat to Himalayan regions for a long time, especially since global heating causes glaciers to retreat increasingly, melting ice. This has worsened in recent times.

What happened in Sikkim is a multi-faceted disaster, brought about by rains and the release of extreme quantities of water from the South Lhonak glacial lake, coupled with the release of water from the Chungthang dam.

The death toll stands at 14, and is expected to go up. Over a hundred people are still missing, including 22 army personnel.

ThePrint explains what happened in Sikkim, how GLOF events occur, and mitigation efforts that are underway globally to prevent such disasters.

Also Read: Himachal to ‘consider controlled riverbed mining’ to curb floods but environmentalists sound caution

What are GLOF events?

The Himalayas are often called the third pole of the world because of the quantity of ice they hold. As the Earth heats up, ice melts and forms giant lakes in depressions created by the weight of glaciers.

This leads to the formation of a glacial lake, which acts as a dam and holds water. As more and more ice melts, the risk of such lakes overflowing increases. But more importantly, there is a risk of the structure of the lake collapsing, thus releasing extremely large quantities of water down valleys, in what is described as an “outburst flood”.

These natural dams, just like human-made dams, can also fill up with debris — soil and rock — because of the glacier pushing and inching forward. This debris is called moraine and adds weight to glacial lakes. It is also typically what holds the water in.

A higher resolution look at the South Lhonak Lake GLOF. Water level has lowered but the lake still stretches >2km shown by the smooth surface of the floating ice/sediment @icicle_diaries @BhambriRakesh @vimalkhawas @WaterSHEDLab @Upadhyay_Cavita @realglacier @GlacierHazards pic.twitter.com/pXj4l4QvBk

— Scott Watson (@CScottWatson) October 4, 2023

GLOF events have occurred throughout history, and scientists have ample evidence of this having happened in the past, unleashing megafloods. They can be caused by earthquakes or volcanic eruptions, but also by increased melting of ice.

The riskiest region in the world for GLOF events is the Indian subcontinent through the Himalayas, followed by the Peruvian Andes system, threatening nearly 10 percent of the world’s population, located in India, Pakistan, and China, as well as Peru.

A total of 90 million people are at risk around the world, in 1,089 basins that contain glacial lakes, according to a study conducted by UK and New Zealand researchers, published in February. GLOFs occur regularly in India, Pakistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and Tibet in Asia. Several flooding disasters in the Himalayan regions have been caused by such GLOF events, including the 2013 Kedarnath floods that killed thousands of people.

What happened in Sikkim

The main source of water in Sikkim’s deadly flash flood was the South Lhonak glacial lake, in the Upper Teesta Basin. Studies of this lake have shown that due to increased ice melt, the lake was growing rapidly in size.

In the early hours of Wednesday, an intense cloudburst occurred over the South Lhonak lake, filling it up with water, causing it to collapse. This released the deluge, which washed away buildings, bridges, and people in their beds.

The water also destroyed the Teesta Stage III Hydro Electric Project’s Chungthang dam. Built in 2017, Teesta Stage III is the largest hydropower project in Sikkim.

Houses, buildings, and other establishments along the Teesta river and Lachen Valley were swept away in the floods before daybreak. Communication towers were also affected, resulting in loss of mobile network. The collapse of highways and bridges have left major regions inaccessible, including Gangtok.

Seismic signals caused by the floods were detected as far away as Kathmandu.

We may even see the seismic signal of this flood as far as Kathmandu, over 300 km away! Data from both Everest and Kakani stations show an increase in seismic noise at the same time. Timing seems consistent with the gauge information… https://t.co/hvp47ZKMd2 pic.twitter.com/ic65Pdz4Ld

— Kristen L Cook (@Kristen_Cook_) October 4, 2023

Although there were concerns that the 5.7 magnitude earthquake in Nepal the previous day might have triggered the flooding, satellite data seems to indicate that extreme cloudburst over the South Lhonak lake led to a GLOF event, which caused the disaster.

A before and after of the South Lhonak Lake GLOF. Clear moraine incision and lake level lowering. Lake area decrease at the calving front could be due to floating ice rather than infill @icicle_diaries @BhambriRakesh @vimalkhawas @WaterSHEDLab @Upadhyay_Cavita @realglacier pic.twitter.com/wl7FTRNYal

— Scott Watson (@CScottWatson) October 4, 2023

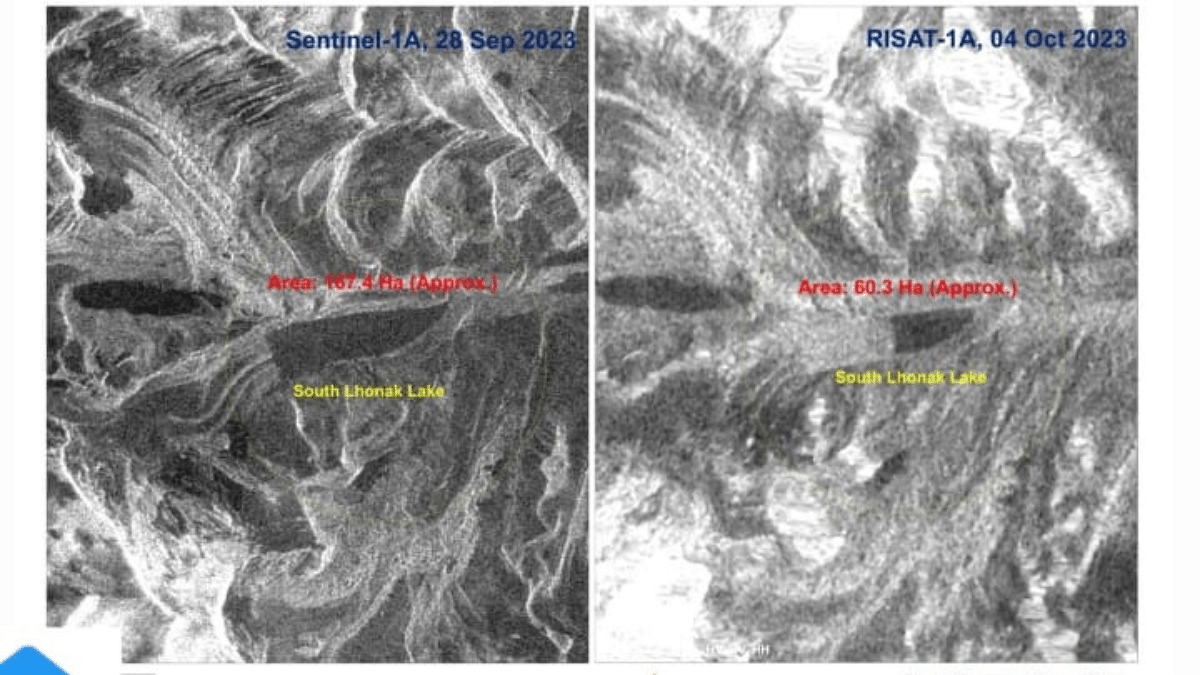

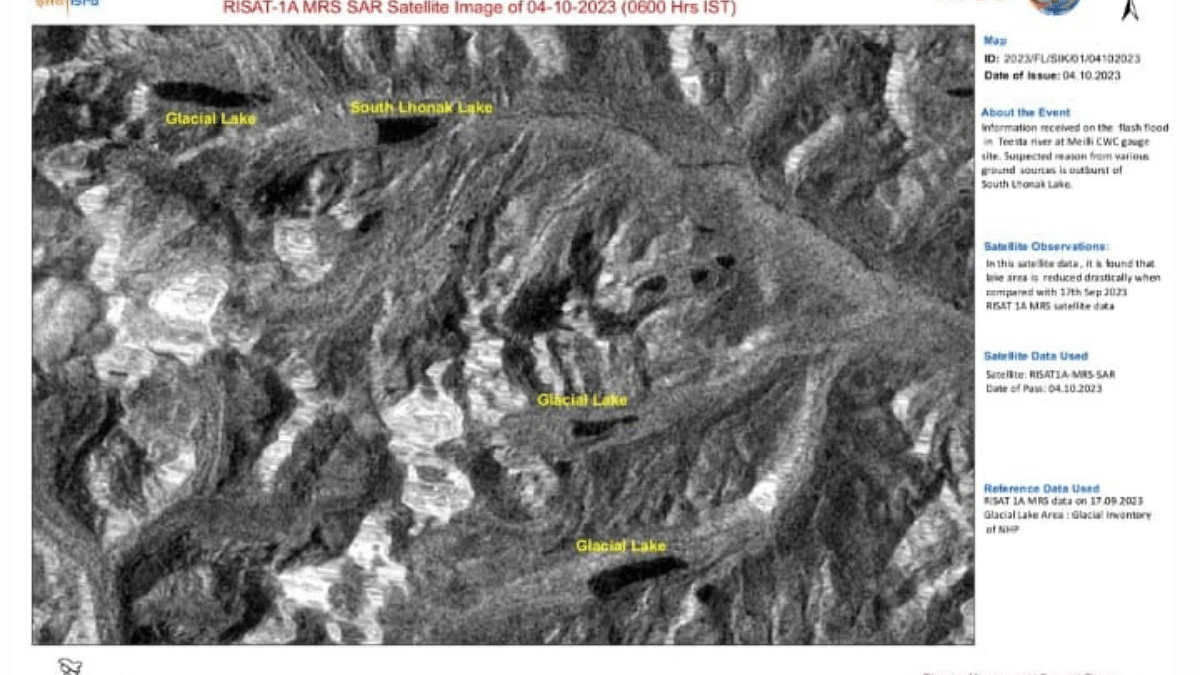

Images released from ISRO seem to confirm the same.

Images released by @isro confirming that South Lhonak lake burst. So this is confirmed to be a GLOF event now.

Teesta III hydroelectric project in Chungthang, Sikkim was overwhelmed by a GLOF event. Sobering, all those years of paper warnings come true in real life.… pic.twitter.com/55sLGs6VQv

— Anand Sankar (@kalapian_) October 4, 2023

Protection measures against GLOFs

After two major flooding disasters in 1980s, Nepal has taken active measures to reduce casualties related to GLOF. For instance, a growing lake near Mt. Everest was drained in 1999 to lower water levels — the first such activity performed in the Himalayas.

Nepal has investigated glacial lakes enough to be able to identify risk levels enough for GLOFs.

A 2020 study identified nearly 50 potentially dangerous glacial lakes, of which less than half were within Nepal’s borders.

Peru is held up as an example for GLOF mitigation. It has been working on monitoring glacial lakes and implementing early warning systems after its deadly 1941 GLOF event which resulted in a large number of casualties.

In the Andes, mitigating measures include draining lakes and constructing spillways for glacial lakes to drain without breaching.

India has approached GLOF events as a part of earthquake mitigation measures, through satellite observations, which can warn when a glacial lake needs draining. Ironically, earlier this year, scientists had told ThePrint that they were attempting to explore glacial lake draining in Sikkim.

Also earlier this year, the Department of Water Resources and Geological Survey of India warned a parliamentary standing committee of increased risk of GLOF events due to rapid retreating of Himalayan glaciers. Specifically, the state of Sikkim has been the subject of GLOF assessment studies frequently in the past owing to its well-known risk, as it contains both a large number of glacial lakes, and is also located in a seismic zone prone to quakes and landslides.

A 2021 study showed that human settlements in Sikkim in the Teesta valley were at high risk for GLOFs. A 2020 study named the South Lhonak lake as one of 10 lakes at highest risk in Sikkim, which is home to 35 other glacial lakes. Studies modelling GLOF events for South Lhonak lake showed extreme risk of intense floods.

Glaciologists and disasterologists are also concerned about building dams in the Himalayan region which is prone to regular and extreme earthquakes.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: Hanging glacier, pond, rock mass — scientists studying Uttarakhand floods explain likely cause