The skeletal exterior of one of the newest coal power plants in Cambodia sat silent among farmland in Oddar Meanchey province on a still afternoon in June. Weeds entangling brick stacks, cement mixers and truck tires showed construction had long been paused.

Locals toasting to happy hour down the road from the front gate complained of months of delayed pay for the site’s security guards, adding there was no set date for operations to resume. There was little more information at the Ou Svay commune hall.

“Maybe the plan changed to complete construction by 2025?” questioned Roeun Phearin, who was a commune consultant for the Han Seng power plant. “The construction is now paused and we don’t know the reason because it is the internal information of the company.”

The confusion surrounding Oddar Meanchey’s Han Seng plant is mirrored in other projects that were part of Cambodia’s big bet on coal in 2020. The kingdom doubled down on fossil fuels with plans to develop three coal power plants to meet rising electricity demand that could not be filled by renewables. This would flip Cambodia’s power production, nearly half produced by renewable energy at the time, toward fossil fuels.

The move bucked the global push for clean energy and dismayed sustainability advocates, but the announced plants are now facing years of delay — raising questions about when, or if, the kingdom’s “last” coal projects will go online.

When announced, all three plants were attached to China’s infrastructure-focused Belt and Road initiative. While China’s 2021 pledge to cut support for coal power abroad killed projects elsewhere in Southeast Asia, including in neighboring nations, Cambodia’s plans appeared to survive the chopping block.

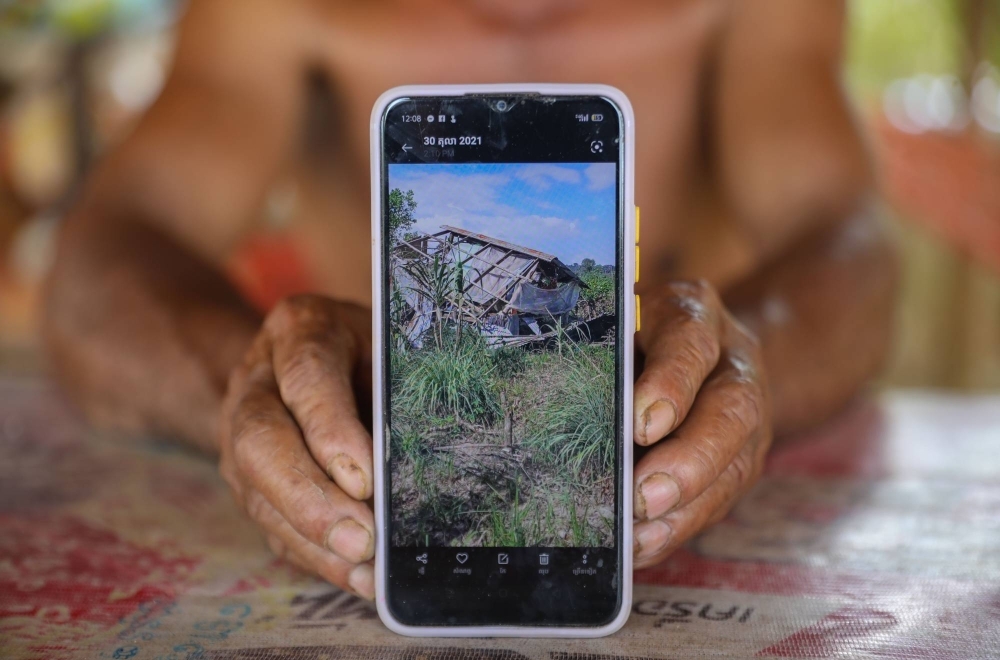

Roeun Phearin, who was a commune consultant for the Han Seng power plant in Oddar Meanchey province, said he had received no new information about the long-delayed coal project.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

While the Cambodian government pledged that these projects would be its last coal plants, two of the three sites are in varying stages of inertia. Meanwhile, the third is finished and operational.

In deeply rural Oddar Meanchey province, the 265-megawatt, half-built Han Seng project missed its deadline to go online last year. Falling revenue for the Chinese companies in charge shifted the project to new contractors, who are sticking with coal — but are also now investing in solar energy at the same plant.

Meanwhile, near the coast in Koh Kong province, the politically connected Royal Group conglomerate has yet to even break ground on a planned 700-MW power plant initially scheduled to go online this year. Former residents of the area say they were evicted to make way for the project and not properly compensated.

Finally, just across the Bay of Kampong Som in Sihanoukville province, Cambodia International Investment Development Group’s (CIIDG) new 700-MW coal project appears to be the only one of the three to have hit its expected completion target.

Just down the same road from CIIDG in Steung Hav district is another plant, the 250-MW Cambodian Energy Limited (CEL) coal complex, which was the first of its kind in the kingdom. The complex’s plants and generators came online in stages between 2014 and 2020. Local residents fear for the effects these power plants could have on their health and the environment.

“This is not good for us,” said fisherman Hang Dara, who left his job as an electrician at CEL because of health concerns. “But it will be much worse for the next generation in this province, since they now have even more coal projects.”

The construction of the Han Seng power plant in Cambodia’s Oddar Meanchey province has been dormant for more than a year with no clear plan for when, or if, construction will resume.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

Future of fossil fuels

While addressing the U.N. in 2021, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged his country would stop building and supporting coal-fired power projects abroad and step up support for renewables and low-carbon energy in order to stay “committed to harmony between man and nature.”

As a major financier and equipper of coal-fired power plants, China’s announcement was hailed as a major step toward achieving the Paris Agreement’s goal to limit global temperature rise by cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

The fate of 77 Chinese-backed coal projects around the world that were in varying stages of development before Xi’s pledge were still uncertain as of October, according to the Helsinki-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

Almost half of those power plants were planned for Southeast Asia.

If the 37 projects in Indonesia, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and the Philippines are operated for their standard 25-to-30-year lifespans, CREA calculated they’d emit a total of nearly 4.23 billion tons of carbon. That’s a little less than the emissions of the U.S., the world’s No. 2 polluter, for an entire year, the center said.

An Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin swims past coal loading docks in Steung Hav, a district in Cambodia’s Sihanoukville province.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

The three coal projects in Cambodia continued to move forward after China’s pledge, but 14 power plants were officially canceled in Indonesia and Vietnam, according to CREA, equating to 15.6 gigawatts of coal-fired energy capacity.

“With the very dramatic drop of costs for clean energy and the increase of costs for coal, the Cambodian government has the chance to re-evaluate if those coal plants are the best way to meet Cambodia’s power needs,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at CREA.

Cambodia is choosing to put itself in an especially precarious position, Myllyvirta said, as the country mostly depends on foreign imports of coal.

“The wild swings in coal prices and global coal markets in the past three years have vividly demonstrated the economic risks of depending on fossil fuels,” he said, adding that price fluctuations would only “become more volatile.”

In 2021, Cambodia imported approximately $222 million worth of coal, according to records from the U.N. Comtrade Database processed by Harvard Growth Lab’s Atlas of Economic Complexity.

The trade data underlines the role of Indonesia as Cambodia’s largest source of coal for more than a decade. Nearly 85% of coal imported by Cambodia from 2012 to 2021 came from Indonesia.

Zulfikar Yurnaidi, a senior officer at the ASEAN Centre for Energy in Jakarta, agreed with Myllyvirta that the future of coal is increasingly uncertain. Yurnaidi said the international “allergy toward coal” continues to be an unaddressed issue for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

“We cannot wish coal and fossil fuels gone right away,” Yurnaidi said. “Support from foreign financial institutions is still required. Maybe not to install a dirty power plant, but to help us reach the end goal of reducing emissions by upgrading fossil fuels and investing in renewable energy.”

Construction on one of Cambodia’s newest proposed coal-fired power plants in Oddar Meanchey province has been dormant for more than a year.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

As coal funding runs dry, international climate finance has risen in Southeast Asia, with billions of dollars going into “just energy transitions” in Vietnam and Indonesia. Following the third Belt and Road Forum in mid-October, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet announced Chinese state-owned power companies had offered the kingdom more than $600 million for renewable energy projects.

Despite foreign funding, Yurnaidi said ASEAN’s emphasis on economic growth will continue to require coal as bloc member-states shift to renewable energy sources.

“ASEAN is a very huge ship with hundreds of millions of people and trillions in (gross domestic product),” Yurnaidi said. “With the energy transition, we know this ship needs to take a turn. But we cannot just make a sudden roundabout because then everyone will fall into the sea.”

Counting on coal

Cambodia’s bet on coal seemed to embody that idea.

In the aftermath of COVID-19, Cambodia’s Power Development Master Plan charted the way for the country’s energy expansion from 2022 to 2040 and predicted a steady rise in energy demand.

The first five years of every “energy scenario” within the plan prioritizes the development of Cambodia’s proposed roster of three new coal sites.

Energy production continues to be a focus for Cambodia’s new government, but the kingdom has made its ambitions for other sources of climate finance clear in upcoming international climate discussions.

The slag heaps of the Yun Khean coal mine contrast with the surrounding pockets of farms and forest two kilometres from the Han Seng power plant in Cambodia’s Oddar Meanchey province.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

The Cambodia Climate Change Summit was held earlier this month in the lead up to COP28, which begins in Dubai on Thursday.

While multiple members of Cambodia’s Environment Ministry spoke of their need and desire for clean energy, Sum Thy, a ministry official who is co-leading the delegation, made it clear that “the key issue we have to discuss is loss and damage.” This refers to the negotiations that will be had at the international climate conference that may determine if low-emitting countries, like Cambodia, should be compensated for climate change impacts.

During a question and answer session at the summit in Siem Reap, Environment Minister Sophalleth Eang, who is joining the delegation to Dubai, said his goals for COP28 are for Cambodia’s priorities to be “taken into account” and hopes these policies will be financed and lead to a positive result.

Ironically, Cambodia’s decision to double down on coal in 2020 stemmed from recent climate change impacts and the country’s past pursuit of renewable energy.

The kingdom had previously met nearly half of its power demands with renewable energy, mostly from hydropower dams on the Mekong River and its tributaries. But severe droughts in 2019 — which some researchers blamed on China’s dams further upstream and others attributed to the impacts of the El Nino climate pattern — led to widespread energy shortages within the country.

Energy experts, such as Chea Sophorn, a consultant who’s worked on projects in Cambodia and across Asia, say these events likely sparked the Cambodian government’s search for alternative energy sources.

But the years of construction delays facing two of the coal-fired power plants have made Sophorn, an energy project manager who specializes in renewable developments, wary of potential energy shortages. He said shortages would depend on how quickly the kingdom’s post-pandemic economy, and thus energy demand, recovers.

The Yun Khean coal mine operates down the road from the construction site of the Han Seng power plant in Oddar Meanchey province.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

But with international investors turning away from fossil fuels, Sophorn emphasized that securing support to jump-start the two stalled projects could be difficult.

“What type of investor will still be able to finance stranded assets like this?” questioned Sophorn, referring to assets no longer able to generate a return due to the transition away from fossil fuels. Without China, he explained, there are few places — or possibly nowhere — for these projects to turn.

Cheap Sour, an official with the Ministry of Mines and Energy, declined to comment and referred to Heng Kunleang, a ministry spokesman, who requested the questions in the form of a voice message and then left them on read without responding. Eung Dipola, the director-general of the ministry’s Department of Minerals, was unavailable for comment.

Construction in Cambodia

In Oddar Meanchey, financial difficulties have already pushed the companies backing the $370 million Han Seng power plant to pivot.

State-owned Guodian Kangneng Technology Stock suffered a massive decrease in its net profit in the first half of last year and brought in a new contractor, Huazi International, in September.

The plan to install 265 MW of coal-fired power hasn’t changed, but Huazi has since announced intentions to add 200 MW of solar capacity to the site. This is the first time any other type of energy production has been associated with the struggling Han Seng power plant.

Just 2 kilometers from the semiconstructed project site, the Yun Khean coal mine, which would supposedly one day supply the plant, is operating as usual.

Boy Troch, who lives a stone’s throw away from the mine’s slag heaps, believes mining operations contaminated the groundwater beneath his farm, damaging crops and sickening wildlife.

The Yun Khean coal mine, which hopes to one day supply a nearby power plant where construction has stalled.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

“There are a lot of lands affected by the mine, but village and commune chiefs do not care,” Troch said, pointing at shifting slag heaps across the road from his land.

With his grandchildren by his side, Troch said he feared coal mining would proliferate in his district if the power plant went online.

“We are afraid to protest because our voice isn’t heard,” Troch said. “We are ordinary people. We are more afraid that they will evict us from this land.”

In Koh Kong, stories from evicted residents appear to validate these fears.

Royal Group, one of the largest investment conglomerates in Cambodia with direct ties to former Prime Minister Hun Sen, received a nearly 170-hectare land concession in 2020 within Botum Sakor National Park for the coal power plant.

People living on the site without land titles complained of rough, uncompensated evictions. Former resident Keo Khorn’s home was torn down in 2021 by a government task force. With 37 evictees, he petitioned for reparations.

“We all came together to complain about the company,” Khorn said. “Everyone heard us, the provincial ministries and the national ministries. But no one did anything.”

Boy Troch lives next to the Yun Khean coal mine in Cambodia’s Oddar Meanchey province. As with many residents of Anlong Veng, Troch served under the Khmer Rouge’s last holdout commander Ta Mok. Today, he’s a farmer and grandfather who sports a gold watch bearing the image of former Prime Minister Hun Sen.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

The project site is currently vacant, but workers are clearing forests around the location. These areas, also within the national park, were given to Royal Group in a second, nearly 10,000-hectare land concession this year.

Thomas Pianka, with Royal Group’s energy division, refused to answer questions.

In Sihanoukville province, where coal plants are actually operating, residents have different worries.

A plant security guard for the older CEL site said other workers have told him about health concerns, but said the company has never mentioned any risks.

The guard’s deputy village chief, Ly Socheat, said she regularly fields complaints about the smell from the power plant. Socheat said many of the families in her village have stopped collecting rainwater in fear of contamination from the coal.

While Socheat attended several meetings about potential employment opportunities at the power plant, she said she has never been informed of any potential health impacts.

Residents complained of respiratory issues and headaches. Living near coal-fired power plants has also been linked to cancer — a 2019 study estimated 1.37 million cases of lung cancer around the world will be linked to coal plants in 2025.

In the waters just off the coast, fisherman Hang Dara recounted why he left his job as an electrician at CEL to instead cast for crabs by the power plant. He believed the plant’s discharged water was heating the bay and harming the environment.

Keo Khorn shows the home he was evicted from after the land he resided on was sold to Royal Group, which plans to use the land for a coal power plant.

| ANTON L. DELGADO

“I was very worried about my health,” said Dara, who explained he had severe headaches and chronic coughs while working at the power station. “But now I am very worried about the health of the fish.”

As Dara stood by the bow of his boat, his fishing partner Loy Chaeum drove from the stern. As they passed coal loading docks supplying the two power plants, Chaeum excitedly pointed out a vulnerable Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin surfacing for air.

“I don’t see many dolphins now, they don’t like the coal. Like us, they must go farther and farther away to survive,” said Chaeum, who explained he motored across the bay every morning in search of a better catch.

That brings him closer to Koh Kong, where one day there may be another coal-fired power plant.

“If they build it, there will be nowhere for them or us to go,” he said, turning back to land, having lost sight of the dolphin.

This article was supported by the News Reporting Pitch initiative from the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Foundation in Cambodia. It was first published by Southeast Asia Globe.