Along coastlines from Australia to Kenya to Mexico, many of the world’s colorful coral reefs have turned a ghostly white in what scientists said on Monday amounted to the fourth global bleaching event in the last three decades. At least 54 countries and territories have experienced mass bleaching among their reefs since February 2023 as climate change warms the ocean’s surface waters, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Coral Reef Watch, the world’s top coral reef monitoring body.

Bleaching is triggered by water temperature anomalies that cause corals to expel the colorful algae living in their tissues. Without the algae’s help in delivering nutrients to the corals, the corals cannot survive.

“More than 54% of the reef areas in the global ocean are experiencing bleaching-level heat stress,” Coral Reef Watch coordinator Derek Manzello said.

Announcement of the latest global bleaching event was made jointly by NOAA and the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI), a global intergovernmental conservation partnership. For an event to be deemed global, significant bleaching must occur in all three ocean basins — the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian — within a 365-day period. Like this year’s bleaching event, the last three — in 1998, 2010 and 2014-2017 — also coincided with an El Nino climate pattern, which typically ushers in warmer sea temperatures.

Sea surface temperatures over the past year have smashed records that have been kept since 1979, as the effects of El Nino are compounded by climate change. Corals are invertebrates that live in colonies. Their calcium carbonate secretions form hard and protective scaffolding that serves as a home to the single-celled algae.

Coral reefs bleach in the Great Barrier Reef as scientists conduct in-water monitoring during marine heat in Mackay Reef, Australia, on Feb 24.

| Australian Institute of Marine Science /Grace Frank / Handout via REUTERS

Scientists have expressed concern that many of the world’s reefs will not recover from the intense, prolonged heat stress.

“What is happening is new for us, and to science,” said marine ecologist Lorenzo Alvarez-Filip at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

“We cannot yet predict how severely stressed corals will do,” even if they survive immediate heat stress, Alvarez-Filip added.

Recurring bleaching events are upending earlier scientific models that forecast that between 70% and 90% of the world’s coral reefs could be lost when global warming reached 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial temperatures. To date, the world has warmed by some 1.2 C (2.2 F).

In a 2022 report by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, experts determined that just 1.2 C of warming would be enough to severely impact coral reefs, “with most available evidence suggesting that coral-dominated ecosystems will be non-existent at this temperature.”

This year’s global bleaching event adds further weight to concerns among scientists that corals are in grave danger.

“A realistic interpretation is that we have crossed the tipping point for coral reefs,” said ecologist David Obura, who heads Coastal Oceans Research and Development Indian Ocean East Africa from Mombasa, Kenya.

“They’re going into a decline that we cannot stop, unless we really stop carbon dioxide emissions” that are driving climate change, Obura added.

Coral reefs are estimated to provide some $2.7 trillion in goods and services every year — with benefits such as attracting tourists, protecting coastal communities from storm surges, and supporting coastal fisheries, according to a 2020 valuation by ICRI’s scientific network.

Global bleaching could be worst yet

With bleaching surveys ongoing in the Indian Ocean and Pacific, NOAA experts expect that this global bleaching event could turn out to be the most extensive yet.

Caribbean reefs experienced widespread bleaching last August as coastal sea surface temperatures hovered between 1 C (1.8 F) and 3 C (5.4 F) above normal. Scientists working in the region then began documenting mass die-offs across the region.

From the staghorns to brain corals, “everything that you can see while diving was white in some reefs,” Alvarez-Filip said. “I have never witnessed this level of bleaching.”

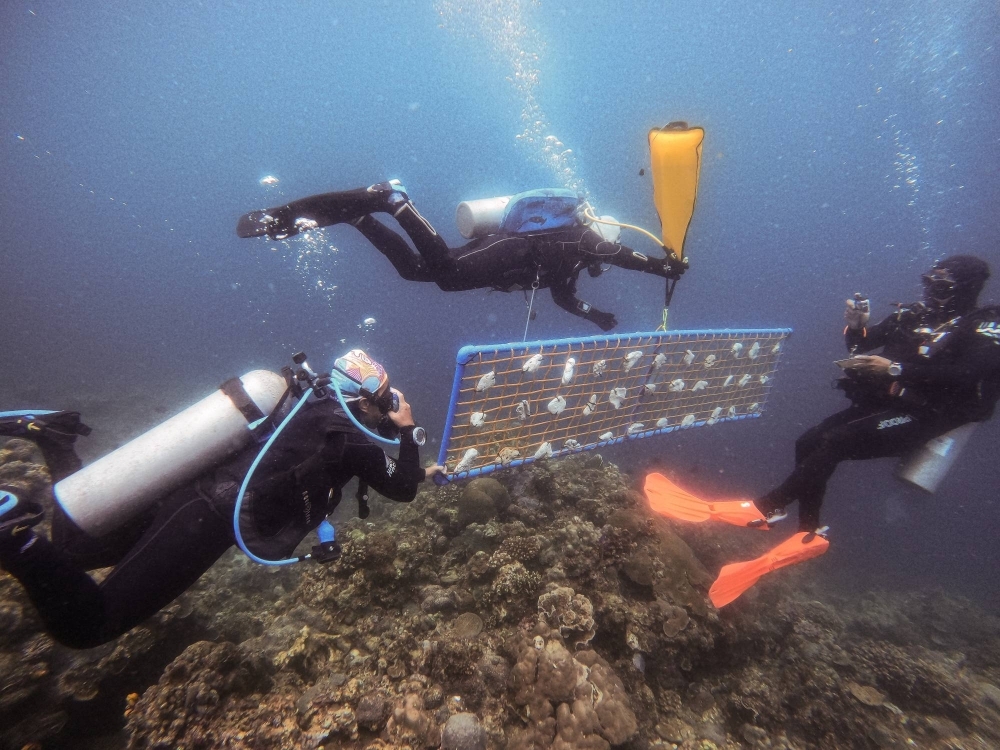

Divers hold a frame for an underwater coral nursery in Bauan, Batangas Province, Philippines, on March 10.

| REUTERS

Bleached corals can recover if waters cool, but some Caribbean corals were so stressed that they continued to die even as temperatures dropped over winter, Alvarez-Filip added.

Florida corals subjected to extreme heat shocks did not even have time to bleach, Manzello said.

“They got so stressed, they just died and sloughed off their tissue,” Manzello said.

At the end of the Southern Hemisphere summer in March, tropical reefs in the Pacific and Indian oceans also began to suffer.

A record-breaking number of individual reefs within the Great Barrier have suffered from heat stress in recent months, and many are now draining of color, said coral biologist Neal Cantin at the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences. Cantin noted that marine heatwaves were registering some 2.5 C (4.5 F) above the normal summertime maximum.

Recent aerial surveys have shown “very high” or “extreme” levels of bleaching in nearly half of surveyed reefs in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park area.

That makes this the fifth bleaching event in the Great Barrier Reef in just nine years — far more frequent than the twice per decade that scientists expected by the 2030s.

Indian Ocean reefs off Madagascar, Tanzania, Kenya and the Seychelles have also suffered bleaching, though not as severely as in 2016 thanks to an early change in this year’s monsoon leading to cooler conditions, Obura said.

“The stress experienced by corals in the region is likely less than it could have been, which is very lucky,” Obura said.