This is Part 2 of ThePrint’s series on education inflation in India. Read Part 1 here.

New Delhi: A 53-year-old business consultant and mother of two in Chennai began setting aside some money each month years ago when her boys were still in primary school. Today, one of her sons is studying law at O.P. Jindal Global University in Haryana, and the other has signed up for a bachelor’s degree in mathematics at Krea University in Andhra Pradesh.

She and her husband shelled out an approximate Rs 40 lakh for their second son’s education at Krea over 4 years. This was in addition to the nearly Rs 30 lakh they spent on their other son’s three-year law degree.

With private universities jacking up their tuition fees and other charges every year, parents across India are reeling from the high cost of university education for their children.

They are saving early, taking loans and even selling property to send their children to expensive private universities in the hope that the investment will pay off eventually with their children’s careers.

Parents often don’t have a choice. They are forced to turn to private universities and fork out lakhs of rupees because the number of seats in government-funded universities, with nominal fee structures, is limited.

“People today are looking for quality education. If their children can’t get into the best public institutions, they often look abroad or to reputable private institutions,” Furqan Qamar, a professor at Centre for Management Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia, told The Print.

The numbers tell the story. Whether it’s a medical or engineering degree, data shows a huge difference in costs between government and private higher education institutions.

According to the 2019 National Sample Survey (NSS), the average expenditure on studying medicine was Rs 31,309 in government institutions compared with a much heftier Rs 94,658 in private aided and Rs 1,01,154 in private unaided institutions in an academic year.

The data covered the July 2017 to June 2018 period. It is the most recent NSS survey on education consumption available.

Engineering students, too, shelled out a relatively reasonable Rs 39,165 for an academic year at a government institute but a much higher Rs 66,272 and Rs 69,155 for private aided and private unaided institutions respectively, revealed the Household Total Consumption on Education in India survey.

But not all government-run educational institutes are within the financial reach of students. Institutes such as the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) and the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) are now charging prohibitively high tuition fees.

For instance, a four-year undergraduate B.Tech degree at an IIT may cost between Rs 8 lakh and Rs 10 lakh for general category students and a two-year MBA programme at an IIM can set students back by Rs 20 to Rs 25 lakh.

Tuition fees have been steadily rising at both government and private educational institutions, leaving parents financially stretched.

In 2016, the IITs more than doubled the fees for unreserved category students from Rs 90,000 to Rs 2 lakh a year, marking the first hike in seven years. Since then, they have been pushing for further increases, but haven’t got government approval yet.

Similarly, annual undergraduate costs at the liberal arts Ashoka University have leapt from around Rs 8 lakh in 2018 to an approximate Rs 12.28 lakh today.

Meanwhile, competition is fierce as demand outstrips the number of seats.

The IITs, for instance, offer only 17,700 B.Tech seats but over 2 lakh students compete for them each year. Similarly, in medical education, more than 20 lakh students take the NEET-UG exam for roughly 1 lakh seats. Only half of these seats are in government-run institutions while the rest are in private medical colleges.

Seats aren’t just limited in engineering and medicine but also the humanities. Delhi University (DU) has just around 70,000 undergraduate seats across 91 colleges, but a staggering 26 lakh students apply each year.

With thousands of students failing to make it to a government university, private universities are the only alternative.

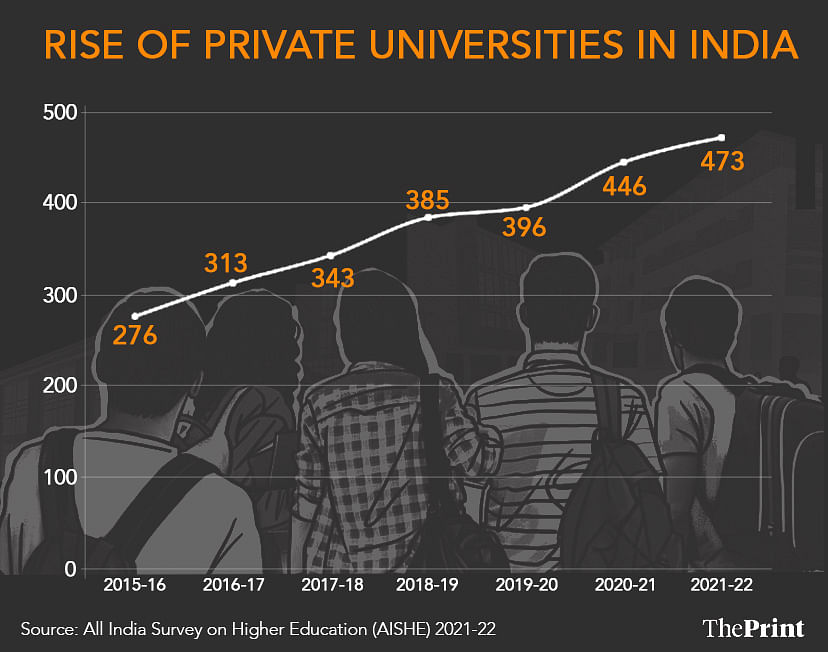

According to the government’s All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2021-22, with demand for private education increasing, the number of private universities in the country rose from 276 in 2015-16 to 473 in 2021-22.

Also Read: Did humanities focus slow India’s progress? New study says vocational education helped China grow

Saddled with loans

Private universities aren’t cheap. It is hardly surprising that their exorbitant costs push many parents to rely on loans from banks or relatives to fund their children’s higher education.

Gone are the days when parents could fund their children’s education with their savings alone.

According to Arjun Chowdhry, group executive (Affluent Banking, NRI, Cards/Payments and Retail Lending), Axis Bank, the increasing cost of higher education as well as an increase in the number of students studying abroad has led to a significant jump in education loan applicants.

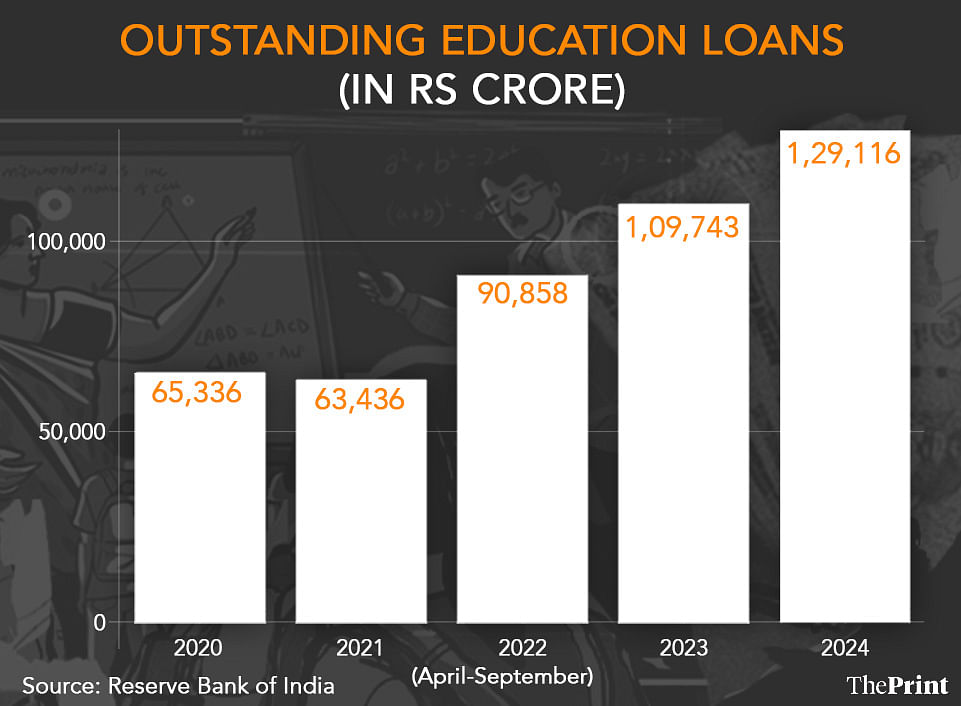

Chowdhry said, according to the RBI, education loans grew by 17 percent year-on-year in March 2023. “There is enhanced interest in this sector with many new players foraying into this space. At Axis Bank, we have witnessed significant growth in our education loans portfolio in the recent years,” he said in an email response to ThePrint.

Axis Bank has borrowers seeking education loans across all income levels and regions.

Apart from the metros, we have seen a higher proportion of students from the four major southern states, Maharashtra and Gujarat seeking admissions to STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) courses both in India and abroad.

— Arjun Chowdhry, Group Executive (Affluent Banking, NRI, Cards/Payments and Retail Lending), Axis Bank

According to a September 2024 report by Credit Rating Information Services of India Ltd, Non-Banking Finance Company (NBFC) education loan assets under management are projected to increase by about 40 percent this financial year to over Rs 60,000 crore from Rs 43,000 crore last year.

RBI data shows that the outstanding education loan balance shot up to Rs 1,29,116 crore in April-September 2024 from Rs 65,336 crore in the same period in 2020. The number had been ticking up since 2020: it increased to Rs 90,858.3 crore in April-September 2022 before it rose further to Rs 1,09,743 crore in the same period last year.

With parents and students desperately scrambling for funds, the government has stepped in to help. On 6 November, the central government approved the PM-Vidyalakshmi scheme aimed at providing loans of up to Rs 10 lakh to meritorious students for higher education at 860 top institutions. The scheme will benefit over 22 lakh students annually.

When private education is the only option

But education loans can be back-breaking for many parents.

A 21-year-old engineering student’s parents working in the private sector in Noida took a loan for Rs 22 lakh for their son’s education at the Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani (BITS Pilani) in 2023. The course fee is around Rs 22 to Rs 24 lakh a year, which is almost the same as the couple’s combined annual income of Rs 24 lakh.

“Both my husband and I lost our jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020,” said the mother, Ankisha Verma.

“We had to rely on our savings just to cover basic expenses—education for both our children, rent and daily needs. It took us nearly two years to get back on our feet. But by then, there was no way we could afford my elder son’s education without borrowing. Although the university offered some financial help, we did need to take a loan to cover the remaining cost,” she added.

The Vermas are confident their son’s B.Tech degree will help him land a good job and repay his education loan.

But for many parents, repaying their children’s education loans can turn into an almost never-ending nightmare.

Anuj Kumar, a middle-class father in Patna, is one such parent who has been struggling to pay off a massive Rs 25 lakh loan he took for his daughter’s business administration degree at a private university in Pune. His daughter’s undergraduate education, including living expenses, cost a staggering Rs 30 lakh, while the family’s annual income is just Rs 20 lakh.

I had hoped that her job would allow us to breathe a little easier, but with the cost of living increasing and her salary just enough to cover her own expenses, the EMI payments are a constant strain on our family. Taking a loan larger than my entire annual salary was a heavy burden on us since I am the sole breadwinner for the family … We have given everything for her education while putting our own dreams on hold.

— Anuj Kumar, a parent

Better quality and infrastructure

Not all parents choose private colleges because of limited seats at government institutions.

Several parents ThePrint spoke to said they chose a private education even though they had the option to send their children to government colleges because of the quality of education and better infrastructure.

According to a 2022 research paper titled Private Financing and Access to Higher Education in India during 2010 to 2020 by Vishakha Gandhi and Kinjal Ahir, scholars from Sardar Patel University in Gujarat, and available on ResearchGate, the proportionate share of private institutes and enrollments has increased consistently and rapidly while the share of public institutions has either stagnated or declined.

The paper showed that enrollments at private unaided colleges consistently increased while government and private aided colleges saw a decline.

And according to the AISHE report 2021-22, out of 1,168 registered universities, 685 are government-managed, 10 are aided private deemed and 473 are unaided private universities. It found that private unaided colleges accounted for 59 percent of the total number of institutions but only 37 percent of enrollments in 2010-11.

By 2019-20, the share of enrollments at private unaided colleges rose to 45 percent, while the share of government colleges fell to 34 percent. Meanwhile, the share of enrollments at private aided colleges also dropped from 24 percent to 21 percent.

The paper also found that households spent an estimated 15.3 percent of their total expenditure on higher education in rural areas and 18.4 percent in urban areas.

Ankit Kumar, a resident of Delhi, said although his daughter could have attended a public medical college, they chose a private institution because of better hostel facilities and infrastructure. “Which government college can offer the same level of infrastructure as private universities? I feel if the parents can afford they will always choose good private colleges over mid-level government colleges,” he asked.

Jamia Millia Islamia’s Qamar, who published a study in the Journal of Higher Education Policy and Leadership Studies in 2021, acknowledged that private institutions have improved their quality, particularly in the last two decades.

Private institutions, especially enlightened ones, are becoming more quality-conscious. They are hiring better faculty and, as a result, their research and publication records are improving…However, research in private institutions is still limited due to financial constraints—most rely solely on fees for funding, unlike public institutions which have broader access to resources.

— Furqan Qamar, Professor, Centre for Management Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia

He noted that more parents who can afford it are sending their children to leading private universities like Manipal University and Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, both ranked among the top 10 universities for medical education in the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) rankings.

“Private universities are doing better every year in both national and international rankings,” Qamar said.

This year, several private universities—such as the Manipal Academy of Higher Education in Karnataka, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham in Faridabad, Vellore Institute of Technology, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences in Chennai and Chandigarh University—made it to the list of top 20 universities in India.

Anju Sharma, whose daughter is studying political science at Ashoka University in Sonepat, said that having attended a public university herself, she noticed a stark difference in the quality of faculty at private institutions.

“The faculty at these private universities bring a wealth of international experience, and the curriculum is designed to offer global exposure. I believe the fee is justified given the quality of faculty and the opportunities they provide,” the Delhi resident told ThePrint.

An undergraduate degree in political science at Ashoka University costs around Rs 36 lakh for three years, which is much steeper than any college under central universities. For instance, Lady Shri Ram College in Delhi University charges approximately Rs 60,000 over three years for a political science degree.

Ashoka University defended the high fee, saying it offered a world-class interdisciplinary education across the natural sciences, social sciences and humanities.

“Our curriculum emphasizes critical thinking and cross-disciplinary learning, setting Ashoka apart as an institution,” the university said in an email response to ThePrint.

Officials at several other private universities also believe the fees are justified considering the exposure and infrastructure they provide.

Professor Dishan Kamdar, Vice Chancellor of FLAME University in Pune, said private universities provide specialised programmes and modern facilities, and focus on quality education with smaller class sizes. “At FLAME University, we measure return on investment (ROI) through a multi-dimensional approach, focusing on both measurable outcomes and transformative experiences. Our goal is to develop professionals and global leaders who can positively impact society,” he said in an email response to ThePrint.

A two-year MBA from FLAME costs up to Rs 19.7 lakh.

Kamdar further said FLAME graduates have gone on to prestigious universities like Harvard, Oxford, University of California, Berkeley, Yale and Johns Hopkins. And their MBA graduates from the class of 2024 had landed jobs across industries such as banking, consulting, retail, marketing and product management.

According to a senior O.P. Jindal Global University official, the university brings together diverse perspectives from around the world, forming partnerships with leading global institutions to create a dynamic learning environment.

All three universities—Ashoka, FLAME and O.P. Jindal—offer a range of financial aid and scholarship opportunities to ensure access to quality education for students from diverse backgrounds.

A former IIT director said a major challenge for public universities today is the decline in faculty quality, deteriorating infrastructure and poor hostel facilities. On the other hand, the quality of faculty at many private universities has improved significantly, even surpassing that of the IITs, he said.

“The education budget has remained stagnant for years. For instance, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) has had to rent out properties just to stay afloat. Bureaucratic hurdles in securing funds for new equipment or academic programmes only worsen the situation,” he told ThePrint on condition of anonymity.

“Private universities benefit from strong financial models and the flexibility to plan their growth. Many IIT professors, for example, have moved to institutions like Ashoka University or others, attracted by competitive salaries and better working conditions. Increasingly, faculty from central universities are seeking opportunities in private universities, lured by better compensation and facilities,” the former IIT director said.

According to the official quoted above, an associate professor’s annual salary at IIT ranges between Rs 16 lakh and Rs 24 lakh, but several private universities pay much more. Salaries at Ashoka University, for instance, range between Rs 16.5 lakh and Rs 28.2 lakh a year. ThePrint could not independently verify these figures with Ashoka University.

Students going abroad also on the rise

Some parents prefer to send their children abroad for a higher education instead of private universities in India. According to data shared in Parliament in August, a total of 13,35,878 Indian students are currently pursuing higher studies abroad. This marks an increase from 13,18,955 students in 2023 and 9,07,404 in 2022. Canada and the US are the most popular destinations for students

The data shows that of the total number of Indian students studying abroad, 4,27,000 are in Canada while 3,37,630 are in the US and 185,000 in the UK followed by 1,22,202 in Australia and 42,997 in Germany.

Parents often take loans to give their children an education abroad.

Delhi-based Arjun Khanna, who works in an IT firm in Gurugram, took a Rs 40 lakh loan last year to send his son to study at a reputed college in the UK.

As a parent, I’ve always believed in giving my child the best opportunities to succeed, which is why I took a loan of Rs 40 lakh to send him to the UK for a Master’s in public policy.

— Arjun Khanna, a parent

“The rising costs of higher education are a heavy burden, but I see this investment as a chance for him to build a future that will ultimately benefit not just him, but our entire family. It’s a gamble, but one I’m willing to make for his dreams,” he added.

Sakshi Mittal, founder of career counseling agency University Leap, said the cost of studying abroad has risen significantly in recent years, especially in popular destinations like the UK and the US. She said a Master’s degree in the UK, which used to cost £16,000 to £18,000 annually just eight or nine years ago, now averages nearly £28,000.

Living expenses in cities like London have also surged, with minimum annual costs now around Rs 20 lakh, excluding tuition, she added.

Mittal pegged total expenses at top US universities such as Boston University and the University of Southern California at about $100,000 a year. “Even with scholarships covering 25-30 percent, students are still left with a heavy financial burden.”

Fees vs return on investment

Parents are divided over whether the huge expense on a private education delivers a significant return on investment.

Some like Aftab Alam, whose daughter enrolled at a private university in Mumbai to study psychology, feel the high fees are justified by the quality of education and opportunities available. The total cost, including accommodation, is nearly Rs 25 lakh.

“The university has strong partnerships with top international institutions, and their placement record speaks for itself. I’m not sure a government college could offer the same level of exposure or networking opportunities,” Alam said.

“It’s not just about getting a degree—it’s about giving her a future full of possibilities, a chance at a life I could only dream of,” he added.

On the other hand, Abhishek Bhandari, whose son graduated from a private college in Bangalore last year, is uncertain about the benefits of a private education.

Despite his son’s degree, he has yet to secure a job. “We paid a steep price for his education, but I’m still left wondering if it was worth it. Will the education truly translate into the career opportunities we hoped for? The financial strain has been enormous, and some days we feel betrayed,” he told ThePrint.

Jamia’s professor Furqan Qamar expressed concern over the financial burden on students in private institutions who took loans but failed to get good jobs later.

“This creates a real risk of disillusionment, especially if they have invested heavily in education without seeing the returns,” he said.

Why are higher education costs constantly rising

Domain experts believe the reason for the fee hikes lies in the business model of Indian universities.

A private university vice-chancellor, who wished to remain anonymous, said private universities in India primarily rely on tuition as their main source of revenue, with fees accounting for around 90 percent of their total funding.

This heavy reliance on student fees, he noted, drives up costs for families.

“In contrast, elite private institutions like Stanford and MIT have a more balanced financial model. Only 20-24 percent of their revenue comes from tuition fees, with the rest funded through endowments, research grants and donations,” he said.

The vice-chancellor added that research is not a significant revenue generator for most private Indian universities.

“In many countries, universities take a 50 percent cut from research grants, which helps support their overall operations. However, in India, research funding is limited, and the universities do not benefit as much from grants, which puts them in a financially challenging position,” he said.

Qamar questioned the sustainability of privatisation in higher education. “India’s higher education sector is vast, with over 40 million students enrolled. The growing number of private institutions caters to an increasingly affluent population, but this trend may make education more elitist and less inclusive,” he said.

“The private sector may continue to expand, but whether it can remain sustainable and inclusive in the long term remains uncertain.”

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Among JEE Advanced toppers, IIT Bombay remains No.1 choice & computer science most popular course