![]()

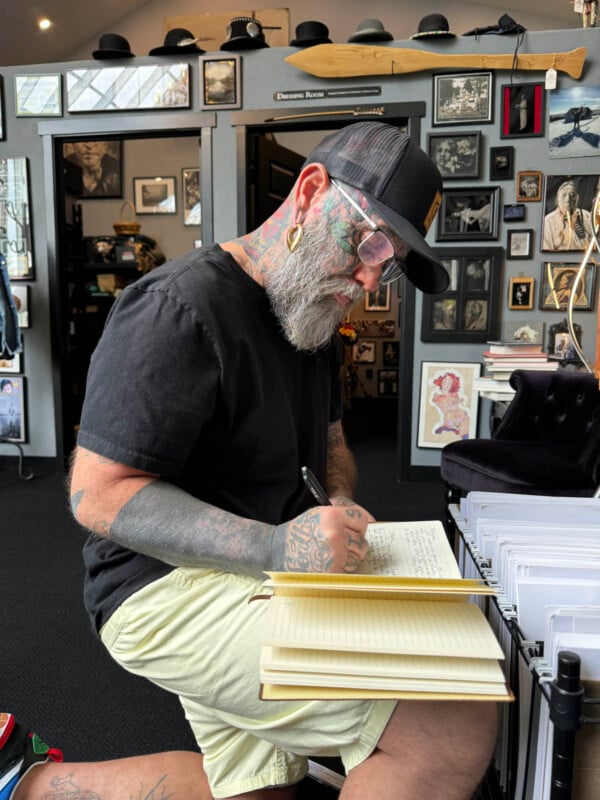

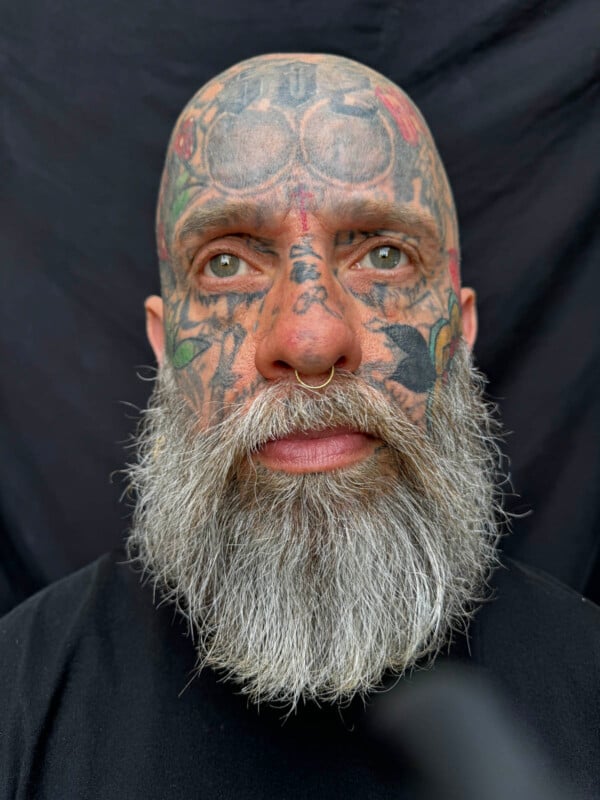

BISMARCK, N.D. – The tattooed man arrived at the photographer’s right on time, a walking gallery of living art in vibrant blues, greens, and reds imprinted all over his face and neck. He sat for a portrait in the studio as scheduled.

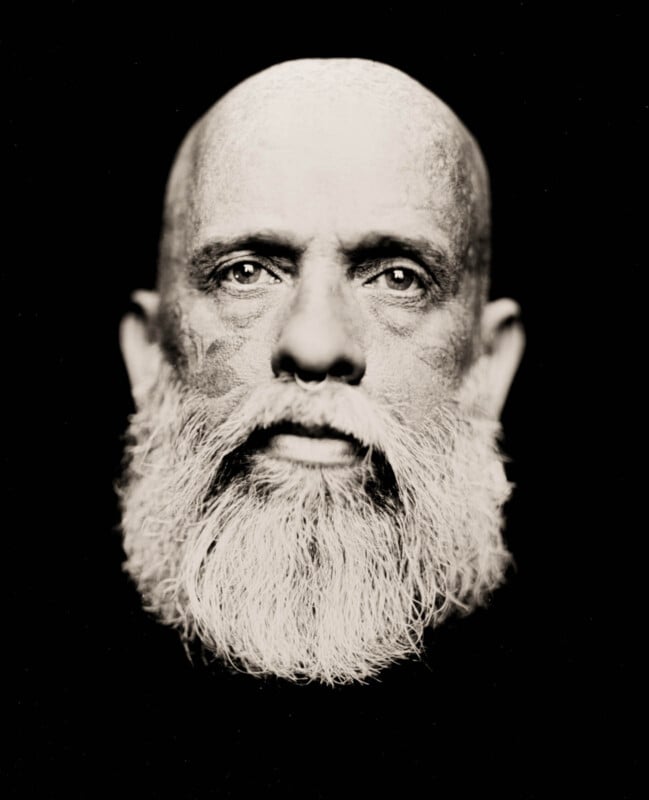

Minutes later, in the darkroom, the tattooed man proceeded to disappear – not as scheduled, but not unexpectedly, either. More accurately, the ink disappeared; and an ordinary, white face emerged, etched in pure silver on a glass plate that captured every line of his face in incredible detail, down to the freckles the tattoos had covered – just not the tattoos themselves.

It’s what photographer Shane Balkowitsch’s study of his craft and its niche in history told him should happen; he just hadn’t seen such a convincing example.

Balkowitsch is one of probably about a thousand photographers worldwide who still practice the cutting-edge technology of 1851, wet plate photography. And although the wet plate method greatly expanded photography and enabled people such as Mathew Brady to document the Civil War, for example, documentary photographers noticed a shortcoming when it came to photographing portraits of Native Americans in tribes that practiced the art of tattooing – the tattoos disappeared.

It’s a topic Balkowitsch knows something about because he is three-fourths of the way done with his own project to photograph 1,000 Native Americans of the 21st century with his 19th-century method. From every set of 250 portraits, he selects 50 of his favorites to go in a book. The third book, Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective, Volume Three, will be published in July 2024.

For Balkowitsch, it’s not so much an act of homage to a 19th-century technique as an acknowledgment that the wet plate method of photography that Frederick Scott Archer invented and described in an article in 1851 has never been equaled in some ways. Pure silver on glass will last a thousand years without fading in sunlight. And the large format of recording the image directly on an 8-by-10 glass plate, in the case of Balkowitsch’s Nostalgic Glass Wet Plate Studio, means the glass plate captures a portrait in remarkable detail – just not the ink of tattoos.

![]()

“I had a Native American woman come in who does traditional tattoos with the tapping,” Balkowitsch recalls. “She said, ‘Shane, I don’t understand why I don’t see photographs of tattoos on Native Americans.’ I said, ‘Because they don’t show up.’”

Balkowitsch knew that from experience.

“I had a bodybuilder come in with a big black eagle on his back—huge black eagle tattoo. I took a wet plate and it didn’t show up,” Balkowitsch said.

But Garold Benjamin Hyatt was even more extraordinary. The Kentucky native figures he’s been getting tattoos since he was about the early 1990s, when he was in his teens – sometimes done by friends who had more enthusiasm than art.

“It was just guys having fun, people that probably shouldn’t have been tattooing,” he said.

His entire face and neck, even the sides and back of his head are now covered in various shades of green, blue, some red – but maybe mostly the first two colors. And that’s significant.

“Things translate in the process – realities change,” Balkowitsch said before his photo shoot with Hyatt. “If he’s got any blue in his tattoos, which he does, that becomes a white, so that disappears.”

And that’s what happened.

![]()

The irony is that the digital photo Balkowitsch shot in 1/60th of a second captured the tattoos in all their shades and hues. But when he had Hyatt sit perfectly still for about 600 times as long – 10 seconds – the camera couldn’t see them.

Balkowitsch explained that what’s going on has to do with the spectrum of the light that the wet collodion method can process.

“We know the wet plate processes uses predominately ultraviolet light to make the images. This is on the opposite end of the spectrum from infrared,” he explained. “The wet plate process is unable to see below the skin’s surface. It cannot see the contrast. The light bounces off the skin and activates the photosensitive silver on the plate with no trace of the tattoos.

In Balkowitsch’s experience, it’s possible for a wet plate image to capture some tattoos, for reasons that may have more to do with the subject and the tattoo than with the photography method.

“Depending on skin color, colors of tattoo, age of tattoos, and type of inks used, there can be some results that will show up,” he said. “If the sitter has very white skin and has very black tattoos there is a better chance that they will show up slightly.”

Even telling the camera what to look at can make a difference, as Balkowitsch saw with a photo of the tattoo of a subject named Amy Hendrickson.

“The wet plate process usually relies on a lens that is wide open which creates a shallow depth of field as well because of the long exposure times. But if the photographer focuses specifically on the tattoo and not the subject, the tattoo can be rendered in the process. It should also be noted that in this example the sitter was very fair skinned and the tattoo was black. It is very uncommon to see tattoos in photographs from the Victorian age because of this limitation. We know that people did have tattoos 170 years ago but the photographic processes used really struggled capturing them.”

Sometimes, Balkowitsch said, it is just that usual problem of the disappearing ink.