Milan’s marble facades and narrow, stone-paved streets look elegant and timeless. But all of that stone emits heat and does nothing to absorb rain, and temperatures and flooding in the posh Italian city are only predicted to increase in the coming decades.

In Jakarta, black floodwaters already rush into homes every winter along the Indonesian city’s many rivers. That water is filled with sewage and harbors disease, but many people can’t afford to move. Soon, climate change will put more of Jakarta — and many other low-lying cities — below sea level.

And in arid San Diego, water is already treated like a precious commodity. As drought increases in the coming years, protecting this resource will become even more important.

Human-caused climate change is transforming weather patterns and shifting ecosystems around the globe. In some places, climate change means too much water; in others, it causes drought. Global action is needed to curb fossil fuel use, slow the rise in temperatures and prevent the worst impacts of human-driven climate change. But significant warming is already baked in.

Cities will have to respond, and some are already taking bold steps. Milan is planting millions of trees. Indonesia is moving its capital city. And San Diego is recycling wastewater back into city taps — one of the first major cities to do so.

Each of these three cities offers a different roadmap for climate adaptation that has lessons for other places around the world. And while no single approach will be a silver bullet, each offers a hopeful vision of how we can learn to live and thrive on a warming planet.

In Milan, for example, the city is working to plant trees throughout the city, rather than just focusing on the wealthiest areas.

“I think it stands out as a successful role model that other cities can learn from,” Matilda van den Bosch, a researcher with the European Forest Institute, told Live Science.

Milan: A forest in the city

Like many cities, Milan is a “heat island”: Temperatures there are 7 to 14 degrees Fahrenheit (4 to 8 degrees Celsius) hotter than in surrounding rural areas. This is because buildings, roads and other infrastructure absorb and reemit heat from the sun better than forests and bodies of water do. And climate modeling predicts things will only get worse, with temperatures in the city rising by up to 4.1 F ( 2.3 C) by 2050.

To address this threat, the city has launched a public-private partnership called ForestaMi — or Forest for Milan — that aims to plant 3 million trees and bushes by 2030. As of 2024, it had planted more than 610,000 trees and bushes. The tree-planting initiative is part of a larger climate plan that Milan hopes will help it keep local warming below 3.6 F (2 C) by 2050.

In the urban planning world, planting trees is a popular climate mitigation strategy. Trees and other vegetation bring down temperatures by offering shade, absorbing and diffusing heat better than cobblestones and pavement, and releasing moisture into the air. Increasing tree canopies over European cities could save thousands of lives by blunting the impact of urban heat waves, according to a 2023 study in the journal The Lancet.

But planting trees may have other benefits, too. Replacing pavement with soil can help cities absorb more rainwater and reduce flooding. That will prove essential in Milan, which climate modeling predicts will face more torrential rain in the coming decades.

But tree planting has limitations. In July 2023, a sudden hailstorm hit Milan, downing 5,000 trees in just 15 minutes, city council member Elena Grandi told Live Science in an email. While storms like this are rare in Milan, Grandi noted, the city will face more river flooding and drought in the future, meaning it will need a mix of trees that can withstand such conditions.

“We have learned that it is necessary to plan urban green spaces in a different way, planting varieties more resistant to storms or to extreme temperature and water scarcity,” Grandi said.

Jakarta: Mass relocation

Jakarta, a megacity roughly eight times larger than Milan, faces both too little and too much water. Sea level rise is already a crisis in low-lying Jakarta, a swampy city that is crisscrossed by 13 rivers.

Jakarta was built during the Dutch colonial era around a series of canals that never quite contained those rivers. Since 1990, Jakarta’s population has more than doubled, further straining the city’s infrastructure. Because Jakarta cannot provide enough piped water to its residents, owners of both high-rise condos and informal shacks dig illegal wells to pump groundwater, said Deden Rukmana, a professor and expert on Indonesia’s urban planning at Alabama A&M University, told Live Science.

This overpumping helped make the city one of the fastest-sinking areas in the world; some places are dipping 4 inches (10 centimeters) per year. Coastal flooding forces people out of their homes, and at current rates, 95% of the city’s coastal district is estimated to be underwater by 2050.

And the risks are not confined to the coast. The combined effects of sea level rise and groundwater depletion will put the entire city below sea level by 2100, modeling predicts. Rising seas also mean that salt water will contaminate the city’s freshwater supply.

To buy some time, Jakarta’s city planners are already building and reinforcing dikes and estuaries closer to the shore. As a next step, they envision building a cluster of 17 islands shaped like a giant bird. Together, those islands would create an 80-foot-tall (24 meters), 25-mile-wide (40 kilometers) seawall and an artificial lagoon that planners hope will help buffer the city from tidal flooding.

But researchers warn that even a huge seawall won’t prevent flooding if overpumping continues to drive subsidence inland. Efforts to relocate water-guzzling industries and to promote development in areas that are less prone to flooding are helping on that front, Rukmana said.

To stay above sea level, Indonesia’s primary city will need to crack down on illegal wells and create alternate water sources, which could take years, Rukmana said. The city could also work to refill aquifers, as Tokyo has done.

But there is another step that could relieve pressure on Jakarta’s groundwater: mass relocation. In 2019, Indonesia announced plans to move its capital from Jakarta to a new city called Nusantara, on the island of Borneo. The first civil servants are expected to move there in September 2024.

Like similar relocations in Brazil and Nigeria, Rukmana said, the project aims to relocate a colonial-era capital to a more central location within the country.

“Without any intervention, people will still move to Jakarta,” Rukmana said. Nusantara won’t change that right away, but it could have an impact over time. When Nusantara is built, the goal is that 10,000 civil servants will have their jobs relocated, he said.

Of course, relocating doesn’t always go as planned. In 1999, Malaysia moved its prime minister’s office from Kuala Lumpur to nearby Putrajaya, also due to water issues. Over the past two decades, its population has increased to 100,000 — but that number is less than one-fifth of the total population envisioned. Rukmana said building a new city from scratch is a big risk but one that could pay off for Indonesia if it provides a new source of development for the country.

So far, Nusantara is mostly just cleared land. But planners envision a smart city built around public transportation, walkable neighborhoods and electrification, with robust digital tools for management — a far cry from Jakarta’s congested traffic, air pollution and overcrowding.

Indonesia recently partnered with the United Nations to get input from people living in Argo Mulyo, an existing village that will be incorporated into Nusantara’s footprint.

Nusantara also has tree-planting goals, which are arguably even more ambitious than Milan’s. The new city will be located on land that was previously used for industrial agriculture; it aims to reforest 204,000 acres (83,000 hectares) of rainforest. At the city’s current planting densities, that would be the equivalent of tens of millions of trees.

So far, however, experts say those efforts are falling short, Mongabay reported. Non-native trees, such as Eucalyptus, are being planted instead of local rainforest species, and a phased approach may be needed to account for the area’s damaged soil. For example, “pioneer” tree species may need to be planted first, followed by typical rainforest species, to replicate natural forest processes.

Nusantara city leaders say they are working on a master plan to address these challenges. In the long run, however, Jakarta still needs to address its own problems, Rukmana said.

San Diego: No-waste wastewater

While low-lying Jakarta struggles with flooding, arid San Diego faces drought. The California city, which gets less than 12 inches (30 cm) of rainfall a year, is predicted to experience hotter temperatures and less-predictable rain as climate change worsens.

But San Diego is in a better place than many cities because its climate adaptation actually began decades ago. When California faced a drought in 1990, San Diego’s water supplier, the Los Angeles Metropolitan Water District, temporarily cut the city’s water supply by half.

“The political leaders in San Diego said, ‘We just can’t have this; we need to create our own water independence,'” Jeff Stephenson, now the director of water resources for the San Diego County Water Authority, told Live Science.

At that point, they began rolling out a low-flow-toilet initiative to reduce household water consumption that inspired similar efforts around the country. But San Diego was just getting started.

Over the past 30 years, the city has pulled just about every lever available to reduce demand. Low-flow toilets were followed by low-water landscaping and a water conservation partnership with inland agricultural areas.

Since it started conservation efforts, San Diego County has successfully halved its per capita water use and reduced its reliance on water from Los Angeles by even more. But water conservation on its own isn’t enough. “You can’t conserve your way completely out of a drought,” Stephenson said. “You’re still going to need water.”

So, the city built and raised dams for more water storage and lined canals to prevent water from seeping away en route from the Colorado River. It built pumps to move water north within San Diego County, partly in case of droughts.

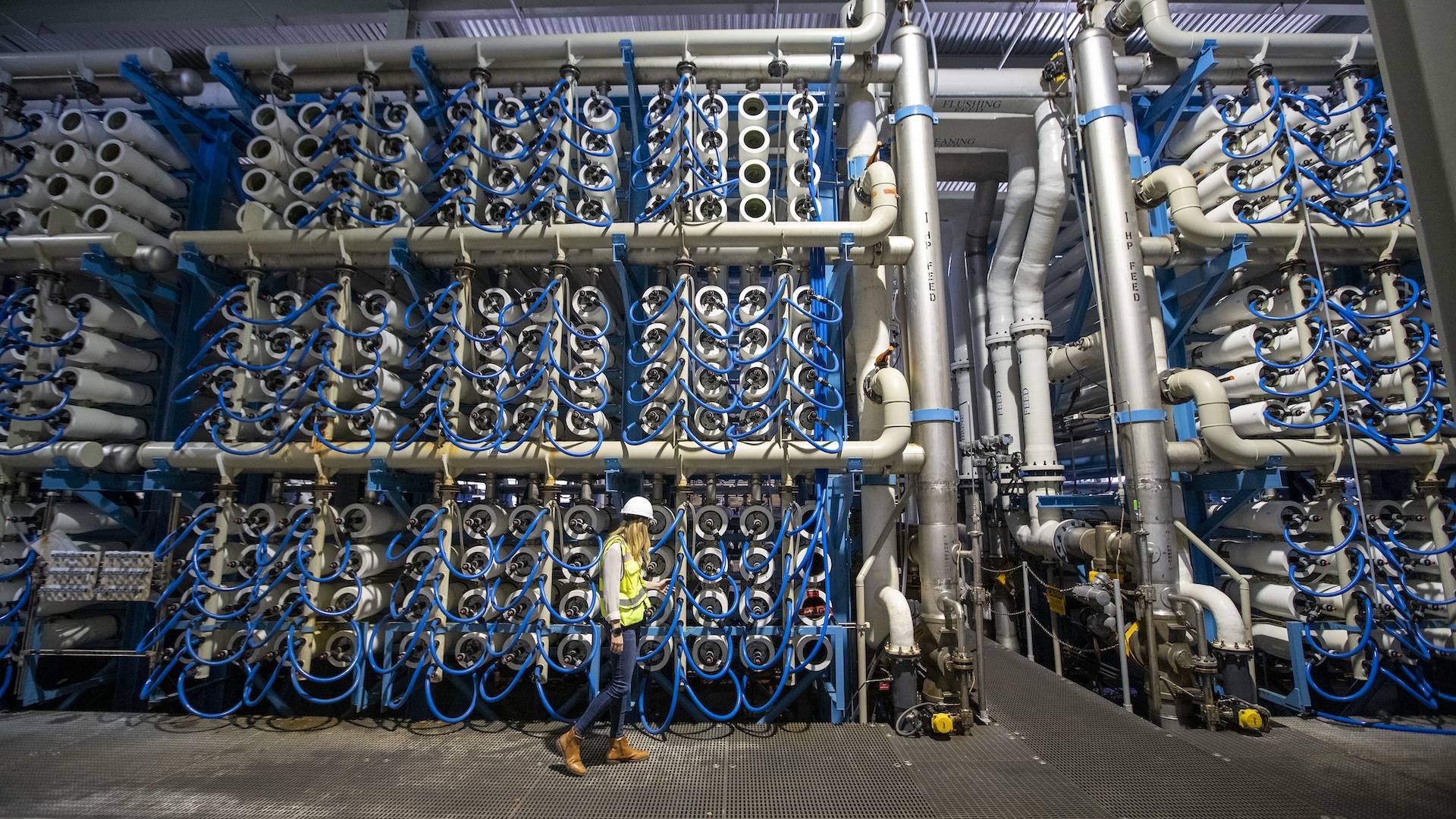

And San Diego also moved to beef up its local water supply. Because the city’s plentiful ocean water makes up for its lack of groundwater, San Diego invested in the nation’s largest desalination plant, which currently supplies around 10% of the region’s water.

After three decades of work, plus a couple of wet winters, San Diego now has water to spare. It’s even planning to lease some of its Colorado River supply to nearby cities.

And facing the likelihood of more climate-driven drought, the city is still aiming to do more. For that, San Diego is again looking to toilets for inspiration. Over the next decade, the city of San Diego and two suburbs plan to recycle wastewater back into city taps. This is a new approach in California. It goes beyond gray water — not-quite-drinkable water that’s used for landscaping. Instead, San Diego will send purified wastewater back into the city’s potable water supply.

That level of purification may sound daunting, but when planners ran the numbers, it was cheaper than other waste upgrades, Stephenson said. San Diego County expects 18% of its water to come from recycled water by 2045.

All of these changes took political will. They also required substantial resources: San Diego benefits from a stable population, plenty of funding and efficient government systems, which many cities worldwide lack.

And for San Diego — as well as Milan, Jakarta and Nusantara — one moonshot project will not be a silver bullet for avoiding climate impacts.

Stephenson encouraged cities to use a variety of approaches — and to stick it out. Change happens one step at a time. “It’s a slow process,” he said, but as in San Diego, the results eventually come.