If you ask what these celebrities were actually like, he cries, “Gorgeous!” The word is so associated with him that in 2015 he brought out a book called Go Get Gorgeous.

Still, he’s had his un-gorgeous moments, and over the years, I’ve interviewed him at critical junctures. After he launched Le Salon Orient, in 1981, he got carried away and opened three other salons, before having to close them with the loss of hundreds of jobs.

“Kim, you got too big for your boots,” he chastised himself over tea in, appropriately enough, the Mandarin Oriental’s Clipper Lounge. It was November 1997, a few months after the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty.

Next time we met, in June 1999, he was crushed but trying to be feisty. Le Salon had, again, found itself seriously in debt and a man called Edwin Hitti had stepped forward to save it.

If you gave Le Salon back to me, free of charge, I wouldn’t want it

Kim Robinson

Hitti was a curious individual, of which there was no shortage in 1990s Hong Kong. He was born in Syria, had a Lebanese passport and had set up a company in Switzerland, which, according to its website, advised government officials in Russia, Zaire, Indonesia, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and “Government(s) of the People’s Republic of China”.

In February 1999, Hong Kong Tatler had run what’s known in the trade as an advertorial, i.e. paid for content, in which Edwin Hitti aired business advice. It was titled “Formula is the Secret”.

The following month, an advertorial on his wife, Cassandra, appeared under the headline “Hong Kong’s Unrevealed Talent”; by the time I met him, Communication Management, which then owned Hong Kong Tatler, was suing him for non-payment. (“They messed up,” Hitti replied imperturbably, when I asked.)

Unfortunately, Hitti and Robinson had already signed an agreement. Matters deteriorated. On March 31, 1999, Hitti applied for an injunction to prevent Robinson having access to Le Salon Orient.

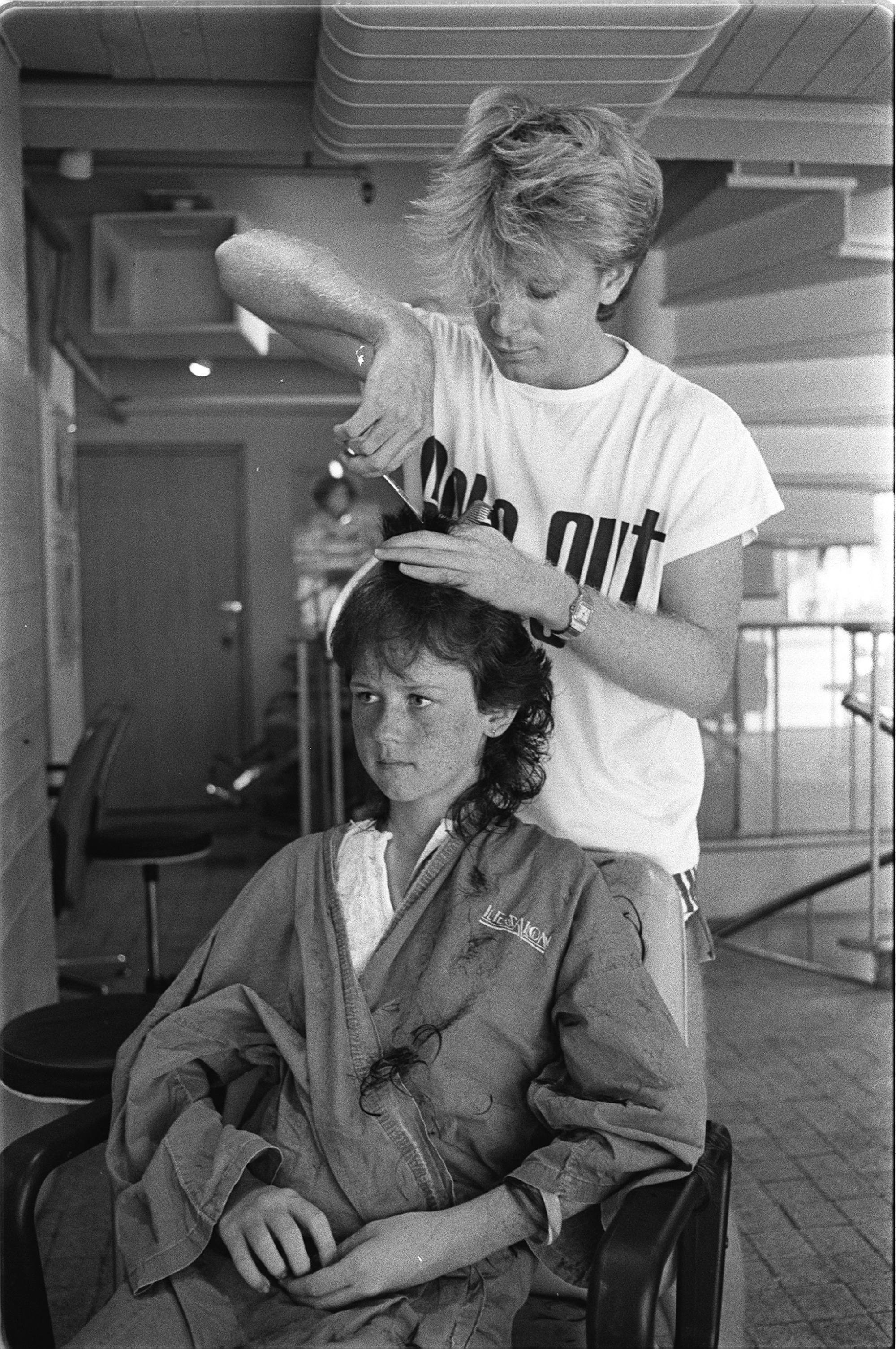

To ensure maximum humiliation, someone had tipped off the press; at the moment it was served, Robinson’s hands were tending to Baroness Dunn’s locks. That her husband, Michael Thomas, was Hong Kong’s former attorney general gave proceedings an added frisson.

Further litigation ensued. A judge thought the behaviour of Hitti’s lawyer “inexcusable” and chastised him for reading the order aloud to an audience that included “a large number of the ladies of Hong Kong high society”. Hitti left Hong Kong.

Robinson’s house in Shek O, which had been used as collateral, was claimed by his bank. He moved in with friends. When we met, during this period, I asked him how much money he had. He counted HK$3,000 in notes and said, “That’s it.”

He also wanted young hairdressers to be coached in the art of being Kim and, to this end, Salon Engineering had been set up in To Kwa Wan, a working class neighbourhood in Kowloon, where Robinson was already spending rather more time than he had expected.

He adopted a defiantly buoyant tone. “If you gave Le Salon back to me, free of charge, I wouldn’t want it,” he told me. Ying, asked for an opinion on the relationship, remarked with great prescience, “Kim is not somebody you can, so to speak, employ … This is like a marriage.”

Within a couple of years, the pair were divorced. In 2002, with Anita Mui as guest of honour, Robinson opened his salon in Chater House. He called it, in case there was any doubt, kimrobinson.

Decades pass. His customers stay loyal. In 2015, he’s one of Debrett’s Hong Kong 100, an eccentric compilation of people considered vital to the city’s daily life. In 2019, rumour has it that he’s ill. What with one thing and another, we don’t meet again until he sends a recent email asking if I’ll write his goodbye-to-Hong-Kong story. (“Before it’s general knowledge, I would prefer you to tell the world.”)

On the phone, he emphasises that he doesn’t want a shoeshine job; I assure him he needn’t worry.

Whatever the circumstances, Robinson strives to be upbeat. He isn’t much given to self-analysis (he looks appalled when I ask if he’s ever done therapy) and, unless prodded, he’s disinclined to linger over darker details. When he doesn’t want to answer a query – for example, whether he was bullied at school – he says, “Don’t remember.”

I’m still here. And. I. Love. Every. Day. That. I’m. Here. I’ve had the most incredible journey

Kim Robinson

“I’m a Leo Rooster, can you imagine? Like my mum – we’re exactly the same. We’re just outspoken, loud, confident, bossy. We put on a good show.”

His mother, Glennis, died on New Year’s Eve 2016. In her youth, she’d taken part in amateur dramatics. “After she passed, dad gave me a box I’d never seen before, full of pictures from when she was an actress. She never, ever, ever talked about how glamorous her life was.

“Dad said, ‘She never wanted to outshine you, she lived through you.’ And I cried, cried, cried.”

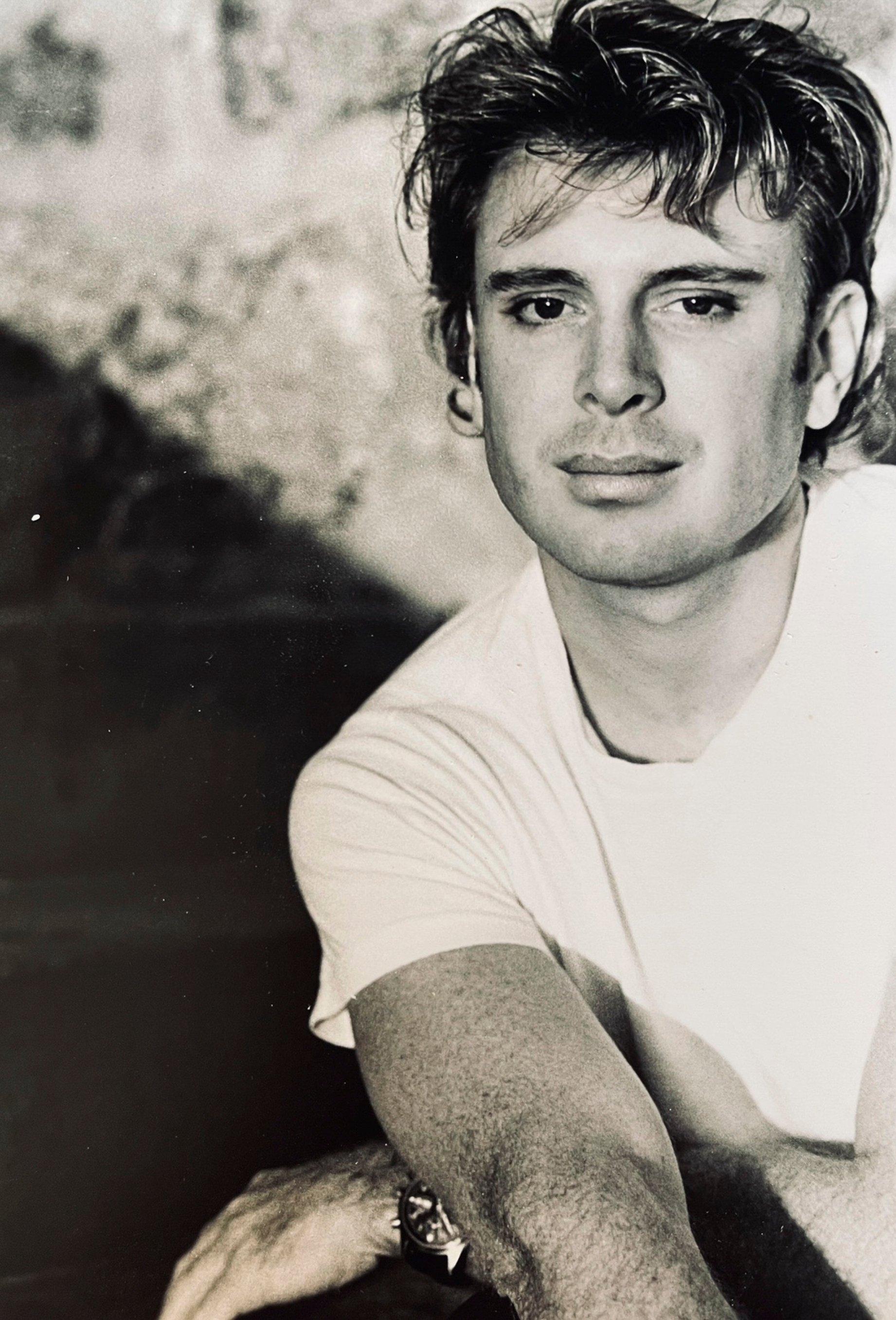

“I used to think I wasn’t handsome compared to my brother but mum said, ‘No, you’re so handsome.’ Mum was biased, she thought heaven shone out of my face.”

His initial reference to that medical crisis is characteristically on message: “I’ve got the same issues they had. I’ve had three open-heart thingies. Anyway. I’m still here. And. I. Love. Every. Day. That. I’m. Here. I’ve had the most incredible journey. I’ve had my hands on the heads …”

Later, he explains that his aorta burst while he was in the salon. (Horrible – but less Alien-grotesque for clients than it sounds, the bleeding being internal.) Most people don’t survive. He was patched up in Hong Kong but what he calls his Los Angeles “face doctor” recommended further specialists.

They told him he had inherited Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which can seriously weaken the vascular system. Without surgery, another aortic rupture could happen at any moment. “Tick, tick, tick, tock,” he says.

“I was so skinny,” he says. “I’ve got pictures you don’t want to see.” Why did he take them? “Because I want to remind myself how lucky I am. You can live in this bubble but the life I’ve lived in Hong Kong – that’s not normal!” His voice rises. Listening to the tape afterwards, it sounds like a wail.

It’s as if he can’t quite decide with what conversational tint he should colour this moment in his life – exceptionally fortunate? Rueful? Frustrated?

“I’ve been a celebrity,” he tells me, at one point. “I’ve worn that jacket, I’ve been to the party and now I feel I kind of stayed too long.” Yet he also says, “I came from nothing, I achieved something. I just think that I’m going to disappear – and then what?

“I go on the MTR and the old people want to take a picture with me. But there’s a whole generation of young people who’ve arrived in Hong Kong and don’t know this guy was one of the success stories.”

The nothingness he came from was the boondocks of Western Australia. Every week as a child, Kim would accompany Glennis into town when she had her hair done. He loved the convivial atmosphere of the salon.

By his early teens, when his father sold the farm and the family moved to Perth, he already knew hairdressing would be his life. “Don’t ask me why. I didn’t have magazines. I didn’t have a glamorous life, there was nothing. My dad’s mates felt sorry for him, they were saying, ‘Well, that’s a bit of a worry.’”

At 14, he was offered a salon apprenticeship. For six months, he says, he would set off for school in his uniform, change clothes on the bus, then head to his job. Eventually, his father found out.

“It was against the law not to finish my education but what could he do? Have me arrested? The boss said, ‘He’s talented, he’s got something special, you should let him do what he wants.’ That’s what my mum told me.”

He was allowed to do a college hairdressing course, where he won the Apprentice of the Year award. A Hong Kong salon offered a job. He watched Love is a Many-Splendored Thing, decided 1950s Hong Kong looked beautiful and flew into 1970s Kai Tak.

“I didn’t know anything.”

His ignorance is corroborated by Leon D’Aulnais, who was manager of the Rever salon in the newly opened (now demolished) Furama Hotel, on Connaught Road, and Robinson’s first boss.

D’Aulnais had arrived in Hong Kong from Elizabeth Arden in London’s Bond Street, in August 1973; a month later, Andros Panayiotou had arrived at Rever from Leonard, in London’s Upper Grosvenor Street. Those were top-end establishments.

As it happens, while I’m writing this story, D’Aulnais, who lives in Sydney in Australia, is visiting Panayiotou, who lives in Cyprus. A video chat is arranged. D’Aulnais recalls telling the “young brash Australian” who arrived “like a rough diamond” in 1976, that if he wanted to succeed in Hong Kong high society, “he’d need to improve his social graces and image”. We all agree Robinson took this advice to heart.

His talent was in no doubt. “He was so passionate and when you’re passionate you become good at it,” says D’Aulnais.

Rever, “to dream” in French, had been founded in 1971 by Anthony Walker and Andre Frezouls. Asked who was already on the scene, Panayiotou vaguely mentions Giovanni (no one, not even the South China Morning Post archive, seems to know his family name) who, it was said, kept a glass of water handy to throw over any customer with the nerve to complain.

It wasn’t, of course, that there were no hairdressers – the Shanghainese influx after 1949 meant plenty were available for Chinese customers – but, beyond the hotels and clubs, Western salons had been sparse.

Hong Kong, too, was polishing up its social graces. In 1977, Hong Kong Tatler was launched. It recorded, and reinforced, a certain level of society within the British colony. By then, Panayiotou had become manager of the Furama Hotel’s Rever.

“Kim and I spent a lot of time together, and we could see what was happening in Hong Kong,” he says. “We wanted to introduce a different class – double the price, new gowns, fresh towels, a reception, we’d serve wine, coffee – and take it to another level. Rever wasn’t having it.”

I changed. I became somebody

Kim Robinson

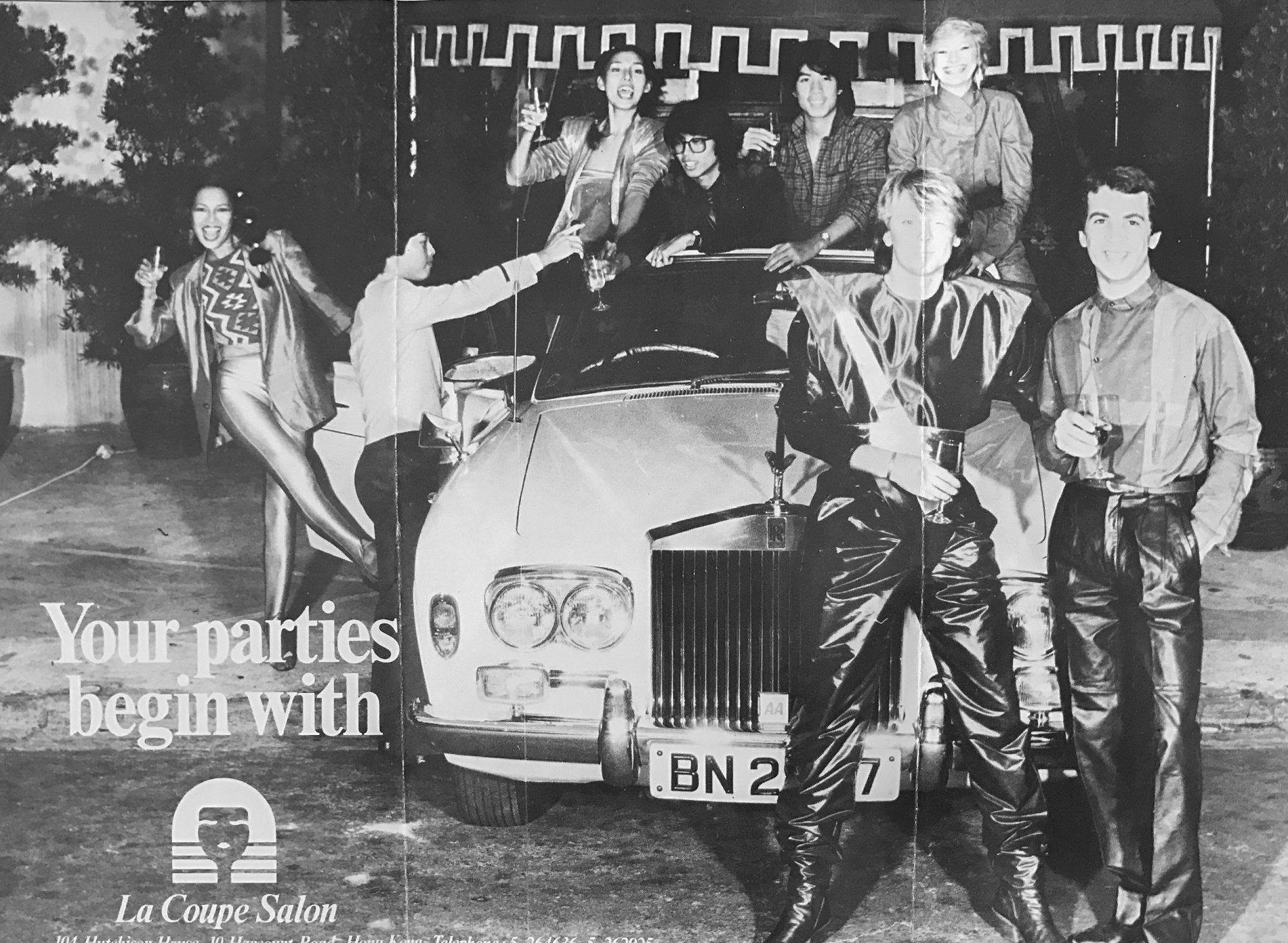

The pair registered a company called La Coupe, and, in 1978, cheekily opened a salon in Hutchison House (now demolished but then next to the Furama Hotel) on April 1. Rever wasn’t going to suffer fools gladly and took them to court. Robinson was banned from working in Hong Kong for six months.

As with Chinese poets, however, exile was the creative making of him. That was when he met Alexandre de Paris; and although Alexandre called him “Imbécile”, made him cry and occasionally fired him, Robinson recognised a true artist at work.

For the next 20 years, he would commute to Paris from Hong Kong for the haute couture shows as the only non-French member of Alexandre’s team. Dry haircuts, the golden ratio, neck elongation, face shape – these are the Gallic concepts that Robinson recites as his creed to this day.

A few years after he returned to Hong Kong, he parted ways with Panayiotou. In 1981, backed by businessman Richard Caring (who was then in the garment industry and now owns a restaurant-and-club empire in London), Robinson opened Le Salon Orient on Hankow Road, Tsim Sha Tsui.

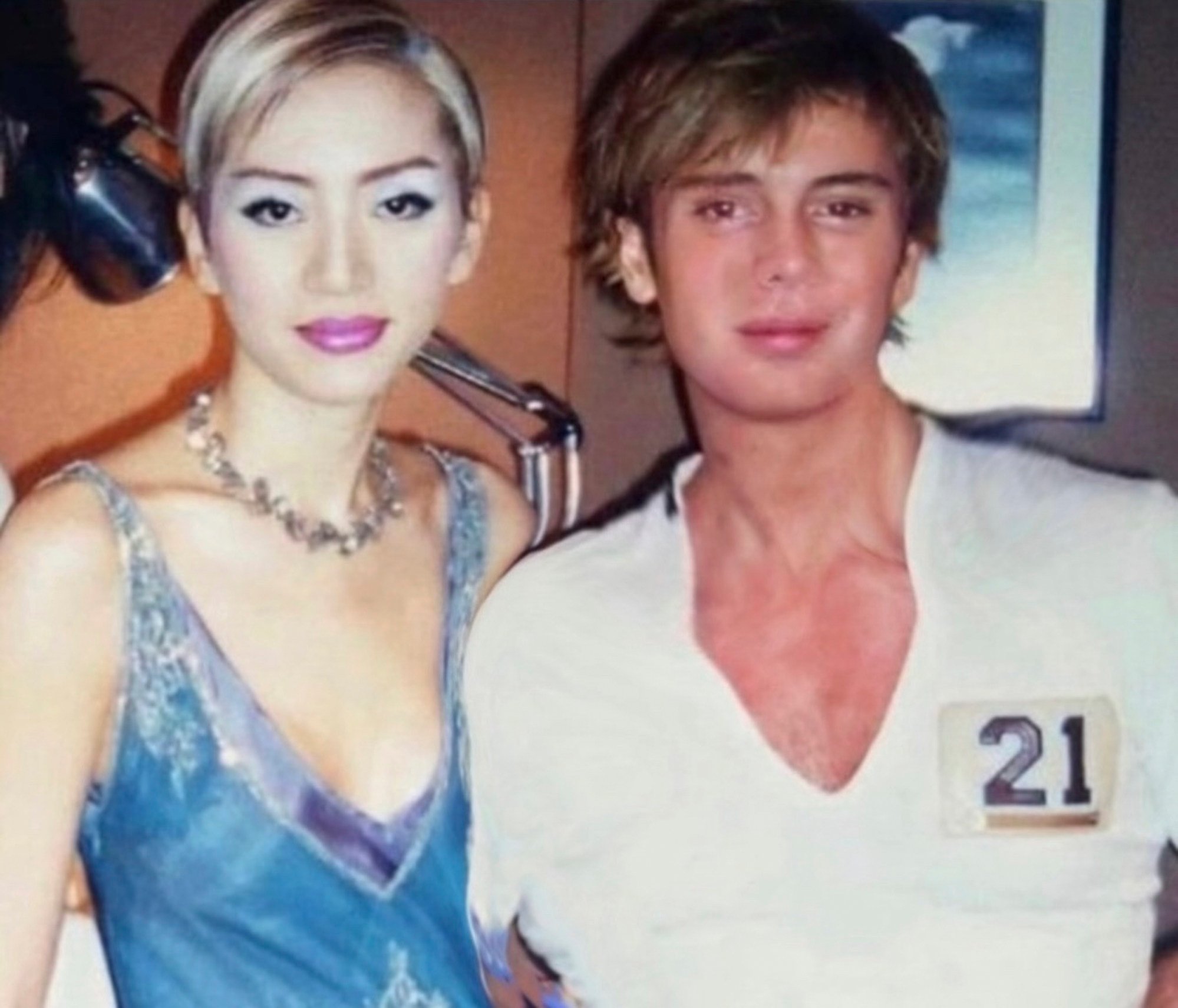

In the Chinese media, he became the foreigner who specialised in Asian beauty. This is why people of a certain age on the MTR, who will never have set foot in his salons, want to say hello.

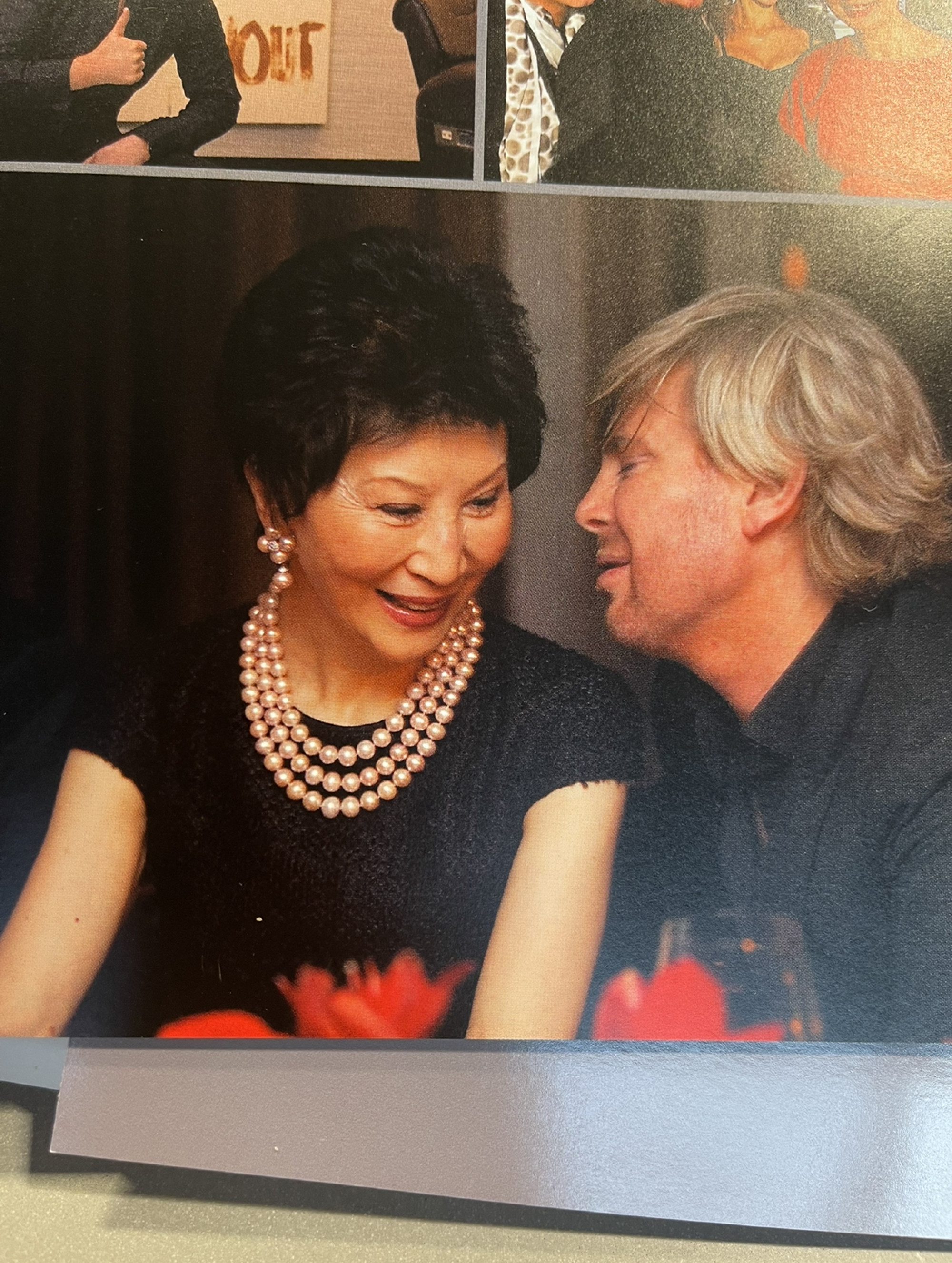

One recent evening, I meet Robinson at kimrobinson. Chater House looks deserted: Armani and Paule Ka have moved out and Hongkong Land has covered the windows with large splashes of text telling its own history as if the present is already past.

His last booking of the day has just left after paying “20-something-thousand dollars” for a treatment. Sometimes he can’t recall the names, he says, but he never forgets the hair colour and his clients are all crying at the thought of his departure.

When I ask who’s going to cut his own hair, he suggests – with a sidelong grin – that maybe he should try where I go, a pleasing but unlikely image. For years, my hair has been done by Doris in her Sham Shui Po living room above the Golden Computer Arcade.

Doris, who’s Cantonese and was born in Kolkata, India, is one of the many women in that now almost-extinct community who’ve been employed by Hong Kong beauty salons since Indian independence, in 1947. She used to work at Talianna on The Peak, now closed, then Talianna at the Hong Kong Hilton, now demolished. She tells me I’m her last Western client.

The atmosphere in Robinson’s empty salon is nostalgic. We sit companionably on the large chairs for which he paid HK$40,000 each in 2002 and now cost – he’s looked it up – HK$80,000.

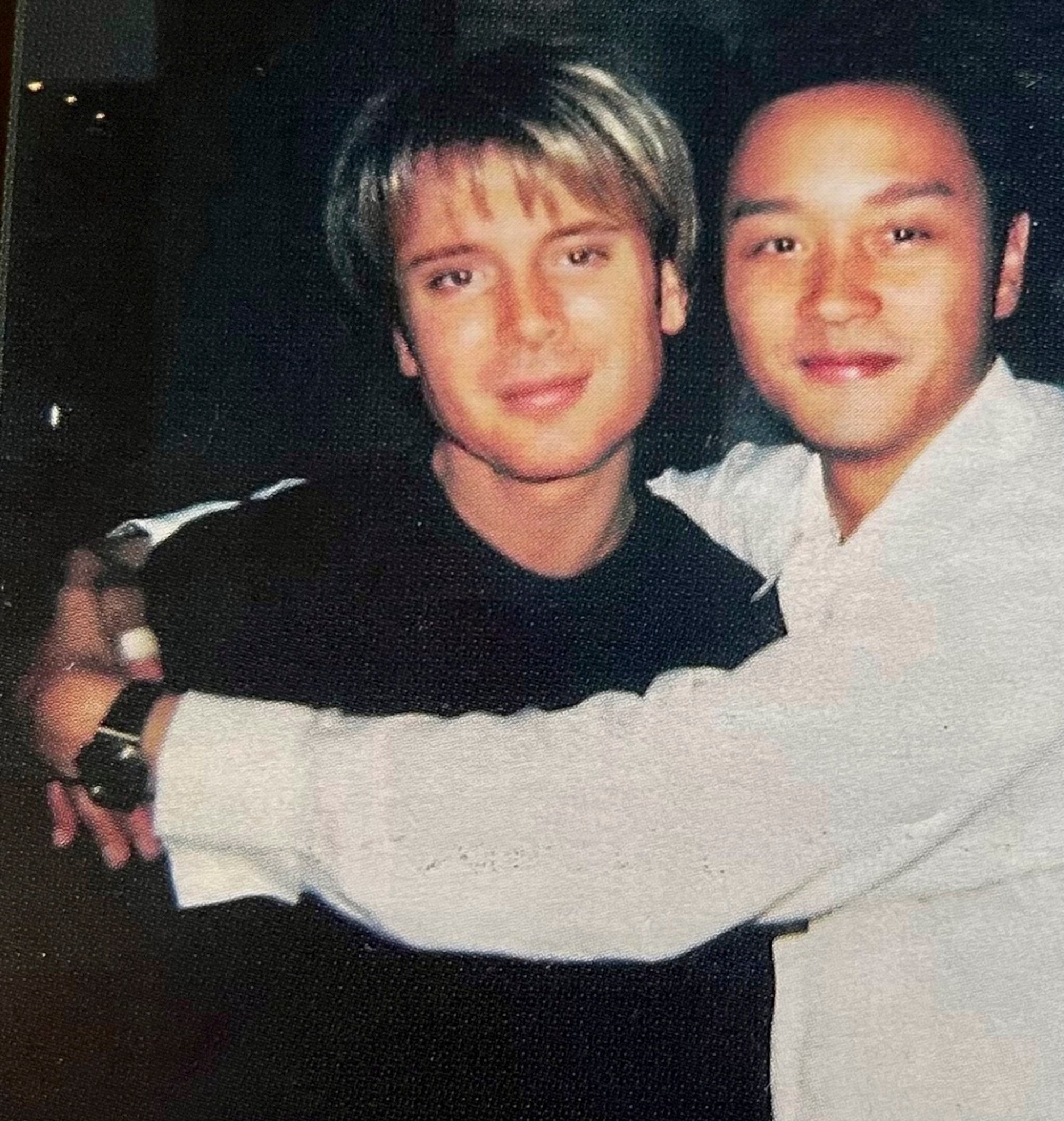

These will be sent to Singapore, where he’s had a presence since 1995; his original salon was opened by Leslie Cheung and Sandy Lam on a fan-packed, traffic-stopping night. He’ll be able to pop in occasionally as he’s involved in a scripted-reality television show (working title: Mr Robinson), produced out of Singapore, in which he seeks Asia’s “next super-stylist”.

D’Aulnais (25 years resident) and Panayiotou (38 years resident) both left Hong Kong once they’d stopped salon work here; Robinson is more vague about any possible departure. “I don’t have to stay in Hong Kong but I want to be in Asia.”

For now, he’s going to focus on a new range of hair products specially developed for Asian hair. “That’s my dream. They’re for a new generation of people that I never had my hands on – it’s a piece of me they can afford.”

Some years ago, he saw Hitti on the street. When? “Can’t remember.” He obviously doesn’t want to discuss it but relents.

“It was like seeing a ghost. He gave me his business card, said we should meet for lunch, la, la, la. Anyway. This is … the fabric of my life.” (According to his LinkedIn page, Lord Hitti, as he now terms himself – the title having been attained by “a dully [sic] enacted bestowment” – is now a polymath mindsetter, a revisionist, a trailblazing logician and president of the Arab Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Hong Kong.)

“I was in awe of her because she was one of the few that let me do whatever I wanted. I made her blond before blond was even cool.” The fabric of his life – the filter through which he’s always seen it – has been hair.