![]()

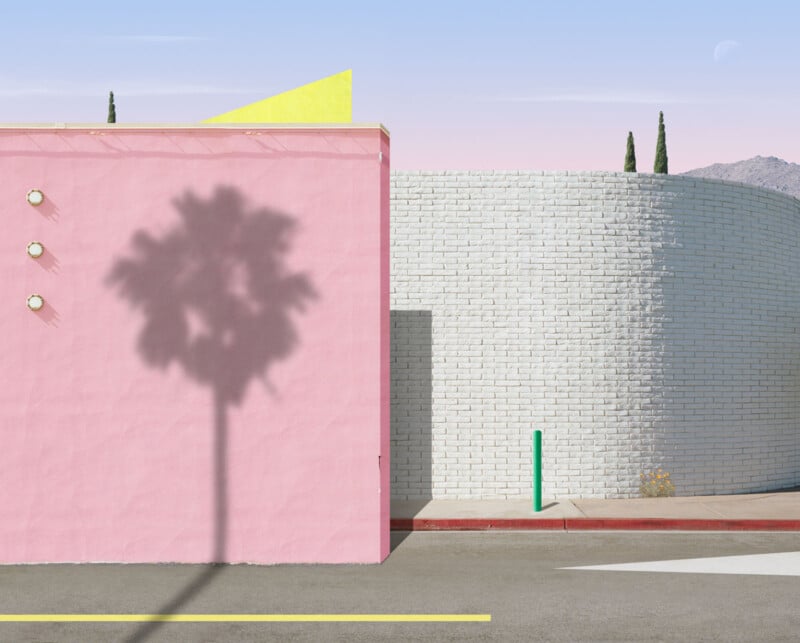

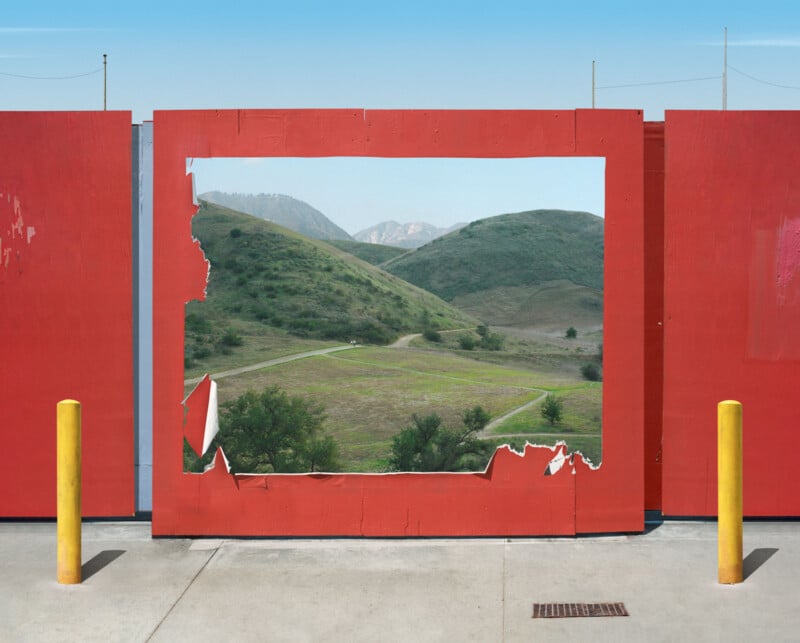

Australian-born, Los Angeles-based photographer George Byrne creates large-scale architectural and landscape photographs that are spiritually grounded in modernist painting, exceptional technical achievements, and, most importantly, successful art.

PetaPixel chatted with Byrne to discuss his latest series, Synthetica. Topics include Byrne’s aesthetic style, photographic approach, how Synthetica fits into Byrne’s larger body of work, and how people’s view of his work has changed in the age of artificial intelligence.

AI or Not?

Byrne’s images are absolutely not AI-generated, but his style and the subject matter have always teetered on the edge of surrealism and offer a glimpse at what can feel like an unreal world.

Art is always viewed and appreciated within the context of the people viewing it, and that is an ever-shifting viewpoint. It’s interesting to consider how people’s views toward AI, technology, and how art is created can change how Byrne’s work is considered.

“Looking back, the timing of the Synthetica show was pretty uncanny. There I was in the studio grinding away on a show I was calling Synthetica, and then AI photography lands. I was like, ‘What the hell do we do with this!?’” Byrne tells PetaPixel. “The technology was still in the beta stage, but it completely blew us away. I’ve been tracking it closely ever since, I find it fascinating.”

Byrne could see a place for AI-generated art in his concept stage to help get ideas into some semblance of form faster and with less work. “But using something like Midjourney to come up with photos using prompts is of no interest to me.”

“I really don’t mind if people think my work is AI generated,” he adds. “There are hundreds of hours of work that’s gone into my images that I’d be happy to show people if they were interested. But really, even if I did use AI, I don’t think it matters, and I don’t judge those who use it.”

“All artists have ever done is use the tools in front of them. My understanding of [AI] technology right now is that it’s a brilliant imitator, aggregator and problem solver. But it’s nowhere near able to compete with human motivation because it has no motivation. It has no lifespan, no mortality, no visceral experience — to me this is where art comes from,” the photographer explains. “But get. Back to me in a year or two and maybe all that will change.”

As for AI technology at large, Byrne says he’s ambivalent but worries for people whose jobs will be threatened by it. He also thinks it’s “crazy that 300 nerds in Silicon Valley should get to release a technology that changes the direction of human civilization without any consultation.”

“Did we ask for this?” he adds. “But I guess that’s always how most technological leaps work. They just happen. And we adjust, and life goes on.”

Synthetica: Creating Real-World Dreamscapes

While at first blush, Byrne’s latest series, Synthetica, looks very similar to some of his prior work, like Inner Visions in 2021 and Color Field in 2017, among others, the photographer notes that there are significant aesthetic and stylistic differences between them.

Yes, there’s a spiritual thread that connects them all, but Byrne has embraced larger-scale planning and compositing that turn his landscapes into dreamscapes, which the photographer refers to as “Frankenstein landscapes that don’t really exist.”

This is a stark change in the process compared to Byrne’s earlier series, which mainly comprised single images subtly changed through post-processing.

There are also conceptual shifts that underlie some of the compositional differences. Byrne’s earlier work was created, at least in part, with social media like Instagram in mind. These images had to work on a smaller scale, so they relied more on large, vibrant color blocks.

In 2021, with Innervisions, Byrne began to shift away from considering Instagram presentation in his process. He cites changes with Instagram as a platform and also the influence of photographer Gregory Crewdson.

“[Crewdson’s] pictures are built to be seen in person, not on screen. He plants detailed symbolism in his images, and there is an epicness that doesn’t translate as well to a 3×3″ backlit screen,” Byrne explains.

Looking closer at the long-term shift in style and approach, Byrne mentions an image from Innervisions called Black Monolith, 2021.

“This was the image that set the table for the work I would go on to produce 2 years later for Synthetica.”

Beyond creating images that aren’t tethered to the need to be understood on a smartphone, there are also narrative differences in Synthetica.

“Synthetica is the first show where I opened the field of view to include scenes from all over America, not just California and Miami. I wanted to use a broad range of subject matter to see if it could be cohesive,” Byrne says. “I felt like this approach would also reflect the American project more broadly, the sewing together of disparate threads into a single, complex entity. The images are about layers, time, and synthesis.”

Looking Closer at the Photographic Process of George Byrne’s Work

For most viewers, it’s easy to appreciate and enjoy Byrne’s work, and there are many different ways to understand each image, as informed by someone’s viewpoint and experience. However, for photographers, Byrne’s work elicits something more: Wonder. How does he do it?

“After years of exhibiting, I see there are two main groups: those who leave their preconceptions of what photography is at the door and just experience the images as if they were paintings, and those who really want to get to the bottom of what’s going on, what’s real and what isn’t, how they’re made, etc.,” Byrne says. “Both are very valid responses.”

“Personally, I’m more the latter, when I see a giant Andreas Gursky or Gregory Crewdson photograph in museum, I tend to analyze every inch of it to see if I can work out how it was made, then, after I have failed at that, I take time to experience the work of art. I think most photographers are like that, it’s hard to shake.”

How Byrne makes his photographs changes quite a bit depending on precisely what he’s creating.

There’s the primary shooting stage of the process, during which Byrne heads out and shoots a bunch of new photos, primarily using Pentax 67 medium-format film and lenses ranging between 75 and 300mm.

Then he “locks himself in the studio for three to six months and goes to work.”

“The first step is trying to familiarize myself with the new stockpile of images, this can take weeks. Then I look for links, for clues. I read a lot of books and look at a lot of other artists. I try to work out what I’m trying to say and think of fresh ways of approaching what I’m doing. I usually end up with 50-60 ideas or ‘sketches,’ then over weeks and months I whittle it down to 15-20.”

Once Byrne has locked in his ideas and sketches based on the images he’s shot, he re-scans all the selected negatives using a high-powered drum scanner. Then, he works with his studio manager, Danny Duarte, to assemble everything into the final composites.

“Danny and I have been working together on assemblage for more than five years now, and his brilliance with post-production is a big part of why my images look so good; we collaborate well. So that’s how I bake the bread,” Byrne explains.

He usually exhibits 15-20 new photographs every 12-18 months.

The Move From Black and White to Color Photography Was Born From Opportunity and Commitment

While the vast majority of Byrne’s portfolio is in color, his very first featured series is comprised of more traditional black and white landscape photographs. It sits in stark contrast to the rest of his work.

“A big part of what led me to where I am is the commercial reality of becoming a full-time artist,” explains Byrne. “When I first started selling the color work I was posting on Instagram in 2014, I was working in a café. I was a seriously broke, struggling musician, and while I loved photography, being an artist was not something I thought was possible.”

However, as interest in Byrne’s work grew, and he was making more sales, he got new opportunities to exhibit his work.

“I quickly dropped everything and became laser-focused on trying to make the most of what was happening,” he recalls.

“I was 37, 38 years old at the time, and aware of how hard it was to get a break. I was very driven.”

The work that helped get Byrne his “break” was his color work, so he redoubled his efforts on the color photography.

“I realized if I was going to get this color work to where I wanted it — in museums — I needed to get serious and upscale what I was doing, get bigger cameras and really immerse myself in the craft, I had a lot to learn both technically and theoretically. I needed also to get clear about what my work was about and what I was trying to say — this is when my five years of art school came in handy!”

“For me to get on top of what I was doing with color photography, I needed to clear the decks and focus on it, so my black-and-white work stopped happening.”

However, Byrne says he hopes to get back to it, and is sure he will “in time.”

That said, one image in Synthetica calls back to the original monochromatic landscape work that Byrne shifted away from. The image, Jenny Lake Wyoming, 2024 may be a color photo, but it is very much like the traditional landscape work Byrne was doing when he was struggling to make ends meet as an artist.

“The inclusion of the Jenny Lake image was a bit of a mystery to me too, it was one of a whole bunch of landscapes I’d taken on a road trip through Yellowstone National Park in 2022. I just loved these landscapes so much and I was a little frustrated that they didn’t fit in, so I thought ‘f*** it.’ I was so taken by this magnificent mountain, and I couldn’t seem to shake the image. So, I made some changes to it, and decided to exhibit it as a lightbox.”

Byrne says Synthetica was partly about departure, experimentation, and large-scale, high-resolution images, so the image fits.

“Mountains have been such an important feature of my work for years, so it started to make sense that I exhibit and impression of one, unimpeded, as a way of paying homage. In the same way that a musician might give a back-up singer an opportunity to get out front and sing a song. I’m not sure if it worked with the other images but I enjoyed doing it.”

Large-Scale Compositions and Large-Scale Goals

“The works in Synthetica do play on scale more than previous work. There are myriad visual misdirections baked into these images that are key to how you experience them,” Byrne explains.

“In this sense, I’m leaning on one of the core principles of Cubism: sewing together multiple counter-perspectives and presenting them to the viewer as a single cohesive whole. The result is a sort of fission in the mind, whereby the harmony of the composition pushes against the disharmony of the formal arrangement.”

Ultimately, Byrne knows that viewers may find different meanings in his work, no matter his goals.

For example, one of his friends recently acquired a print of Black Monolith 2021 because it spoke to her about her perceptions of Los Angeles and her experiences there, in ways Byrne says he never would have considered or thought of.

“That’s the highest praise I could ever hope for! I just hope the work is inspiring to people, that they’re reminded of the magic in the air. I hope my work makes people feel good.”

More from George Byrne is available on his website.

Image credits: All photographs by © George Byrne