In the medieval period, medical science was still dominated by the ancient writings of Hippocrates from the fifth century and Galen of Pergamon from the second century. Research has shown that women were increasingly being taken seriously as healers and as bearers of wisdom about women’s bodies and health. But despite this, men were preferred while women faced restrictions.

Informal networks developed in response, as a way for women to practise medicine in secret – and pass on their medical wisdom outside the male bastions.

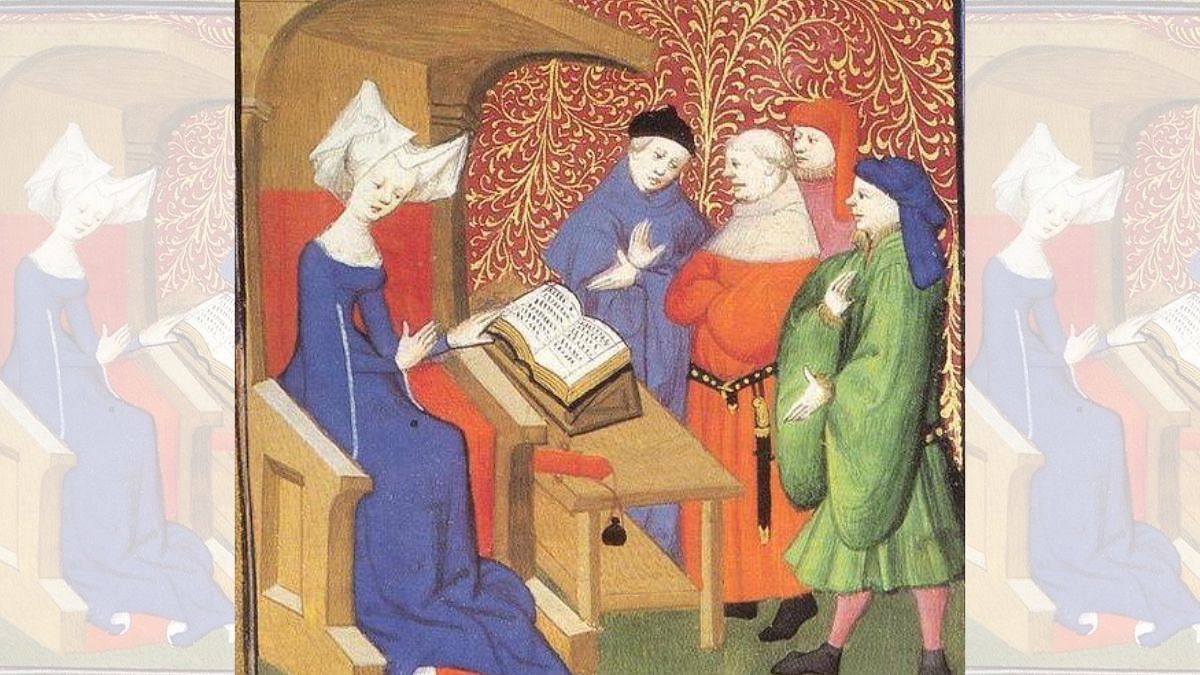

The Distaff Gospels, first published in France around 1480, is a collection of “gospels” around pregnancy, childbirth and health. It was created during secretive meetings of French women who had gathered with their drop spindles and distaffs to spin flax.

These women, who were mostly from the regions of Flanders and Picardy, agreed to meet over the long nights between Christmas and early February to gather the wisdom of their ancestors and pass it on to the women who came after them. The meetings are believed to have been organised by a local villager who selected six older women, each chairing one night, who would recount their advice on a range of topics such as pregnancy, childbirth and marriage.

A scribe was appointed to record the advice, which had previously only been preserved through the oral story tradition of peasant women. What is most fascinating is that although the text is mediated by a male scribe, The Distaff Gospels presents the often-silent voices of the lower working-class women. One such gospel advises:

Young women should never be given hares’ heads to eat, for fear they might think about it later, once they are married, especially while they are pregnant; in that case, for sure, their children would have split lips.

‘Deviant women’

The advice is structured in the way it was shared – stories told to each other while spinning. The women discuss folk wisdom related to their domestic lives, and one of the main sections is about pregnancy and reproductive health.

While researching the history of pregnancy tests for my book, (M)otherhood, I came across this advice offered in The Distaff Gospels:

My friends, if you want to know if a woman is pregnant, you must ask her to pee in a basin and then put a latch or a key in it, but it is better to use a latch – leave this latch in the basin with the urine for three or four hours. Then throw the urine away and remove the latch. If you see the impression of the latch on the basin, be sure that the woman is pregnant. If not, she is not pregnant.

Writing about The Distaff Gospel historians Kathleen Garay and Madeleine Jeay tell us that these texts were written in a mocking fashion, and the scribe describes the women as idiotic, lascivious and even dangerous.

Many of the women healers presiding over these gatherings were thought to be witches or sexually deviant. Nevertheless, through these informal health networks, these women found a way of vesting control and power over themselves, to claim some semblance of autonomy over their own bodies.

Women supporting women

Until the 1400s, medical texts were mediated by men. While women were largely responsible for childbirth advice within informal networks (as women’s naked bodies and anatomy were frequently obscured from men’s eyes), they did not have access to the medical texts that men did.

The Wellcome Apocalypse manuscript, written in Germany around 1420, includes an image of two women sharing gynaecological problems. One woman is seated and naked, while the other (who seems much older) is dressed in rich clothes. The seated woman has a sign on her stomach that represents her vulva.

The image is an example of two women discussing intimate worries regarding sexual intercourse, miscarriages, and problems in conceiving. One says: “My husband’s male member, when banging against the smallness and narrowness of my vulva, the cervix, tired out, forced the foetus to slip out before time.” The other responds: “I too have often been distressed because I am unable to carry a conceived child.”

While medieval women did not have the authority or status of trained medical professionals, some, especially in the upper classes, put together recipes for health and wellbeing. One such manuscript is the early 15th-century Dietary of Queen Isabella, a collection of recipes for maintaining health and combating illness.

Women were also supporting each other’s health through the social network of letter writing. In one such letter from 1455, a woman named Alice Crane writes to her friend Margaret Paston to ask “if the medycyn do you ony good that I send you wrytyng of last”.

As the medical profession became even more institutionalised in the 16th and 17th centuries, women lost much of the respect they’d earned as healers. Many were believed to hold magical powers and castigated as witches. And the informal networks of women sharing medical information, particularly about pregnancy and childbirth, were disrupted.

Today, women still often rely on sisters, mothers and friends for reliable information and to make decisions about their sexual and reproductive health. Globally, the reliance on social networks is often heightened in rural areas, where illiteracy and lack of access to trained professionals and education can be a barrier.

I see these informal networks, whether operating discreetly in real life or in messaging groups such as Whatsapp, as a form of resistance – a safer, supportive and more egalitarian space than institutionalised medical spaces, where women’s conditions and ailments can be ignored or dismissed.

Pragya Agarwal, Visiting Professor of Social Inequities and Injustice, Loughborough University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.