![]()

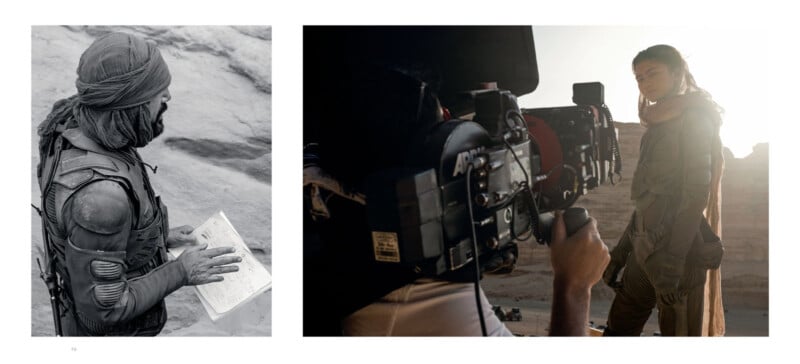

When thinking of major motion pictures and Hollywood blockbusters, it is easy to think about just the movie itself — the final product that makes its way to silver screens worldwide. However, behind every hit movie are hundreds of people and the person capturing all of the hustle and bustle is a unit photographer.

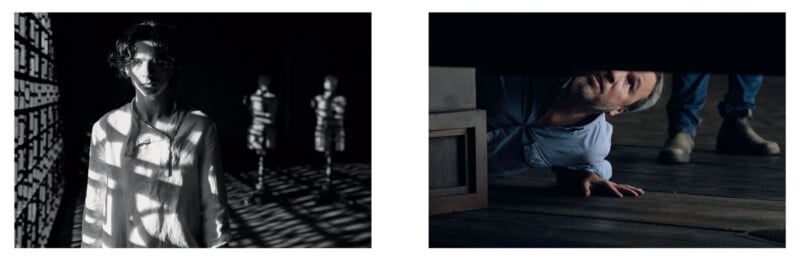

Chiabella James is one such photographer who puts her immense talents to work on film sets worldwide. She has worked on a diverse range of films including King Richard, multiple Mission Impossible movies, Good Liar, The Mummy, Jack Reacher, and, recently, Dune.

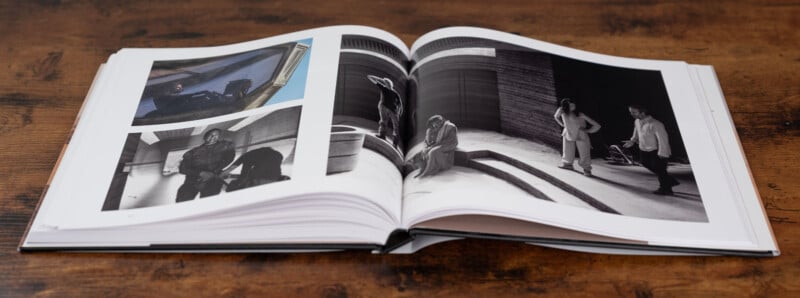

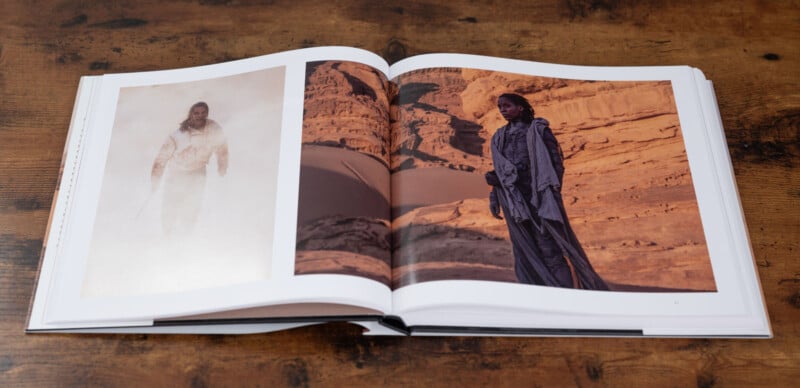

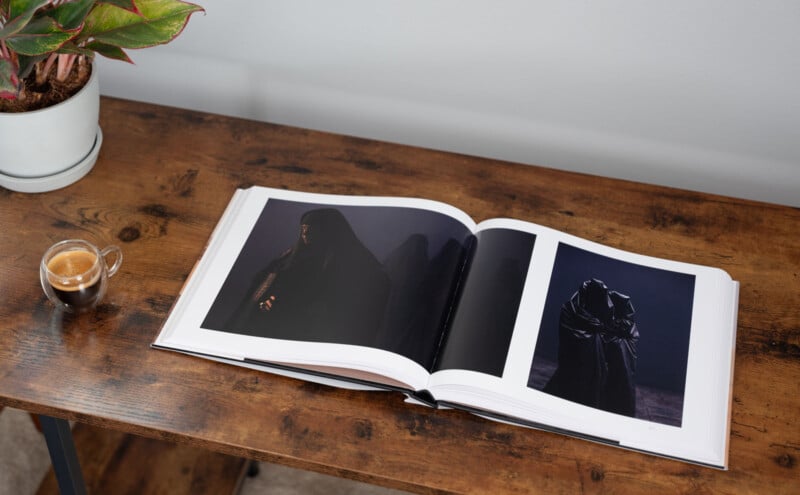

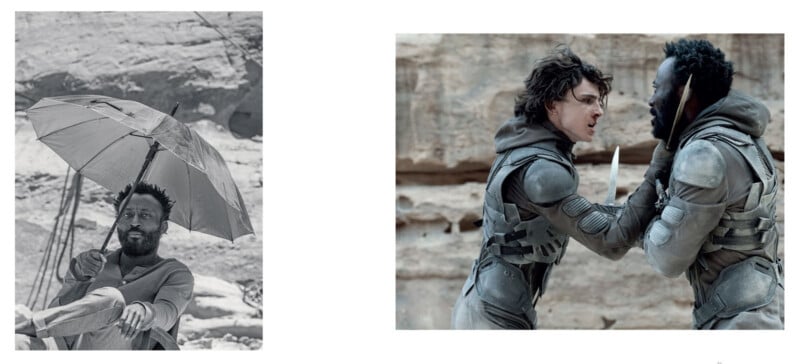

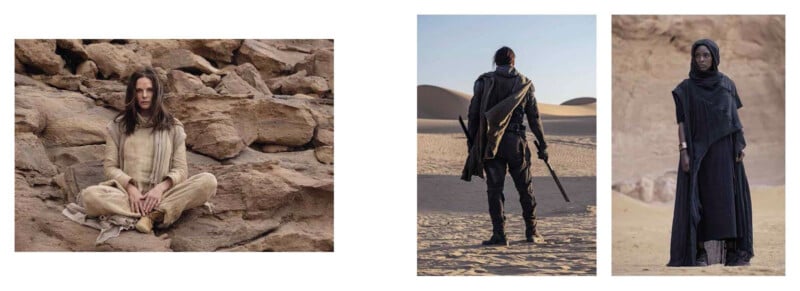

James’ work on Dune is encapsulated in a new photography book, Dune Part One: The Photography, featuring hundreds of James’ photos from working on Dune including stunning landscapes and beautiful portraits of the film’s creators, actors, and the staff who make everything possible. The book is organized by filming location, including Wadi Rum, Jordan; Budapest, Hungary; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; and Norway.

![]()

Growing Up Around Movies and Photography

The “James” surname has a rich history in unit stills photography. Chiabella’s father, David, is a highly accomplished unit stills photographer. He is a founding member and former president of the Society of Motion Picture Stills Photographers and a recipient of the 2011 SOC Lifetime Achievement Award in Stills Photography.

Chiabella spent significant time on jobs with her father as a child, which instilled in her not just an appreciation for photography and a passion for films but a deep understanding of the role that everyone plays in creating a movie. This appreciation for the role everyone plays and how much every single person matters, not just the stars, shows itself through Chiabella James’ work as a professional.

Embracing and Navigating Chaos

Spending so much time on movie sets also helped James acclimate to chaos, which benefits photographers of all kinds, although it is critical for a unit stills photographer.

James tells PetaPixel that sets are even more fast-paced now than when she was growing up and watching her dad work. Even in the last few years of her career, the continued transition to digital filmmaking has changed how she works.

“My father did the same job and gave me some enormous shoes to fill. But the pace of shooting on film versus digital these days is incredibly different. There was a built-in pause when you changed out a [film] mag. There was a delay to get the lighting to a certain level for shooting on film that doesn’t exist anymore. Now you can just hit roll, and we’re going, and you really do feel that on set,” James tells PetaPixel during a Zoom call.

The constant motion on set has made James’ task of capturing interesting behind-the-scenes moments more challenging. “Pausing to wait for those things to happen was a really great window for a still photographer to quietly sneak in and grab those moments and then get out,” she says. “Now you’re begging, scratching, and elbowing to try and get them. It has become quite manic.”

That said, James adds that Dune was the least manic of the recent film sets she’s worked on. “It was incredibly ‘zen,’” she says, smiling.

“Obviously, it was very busy and a lot of hard work; there was a lot going on, but the mentality toward the film’s creation was very zen. You were given time to do your job and do it properly. There was respect for it. It felt very old-school. As a result, you feel like you have the time to do your best, and the results are that much better.”

The Gear

Like any photographer, especially one who works in a chaotic environment like James, she has dialed in a workflow catered to her personal style and approach. As for camera gear, she keeps it very simple. She works with two cameras, one with a 24-70mm f/2.8 zoom and the other with a 70-200mm f/2.8.

“I call it my gun sling. I like to have my cameras on me at all times. I have a body on each shoulder. At any given moment, I’ve got the entire focal length range I need,” she says.

“I’m trying on set to be more like furniture, like something that is always there. That way, I don’t suddenly show up,” James says. “A lot of photographers pride themselves on being ninjas and being hidden. I don’t take that approach. I think if I’m always present, I’m actually less distracting.”

A Healthy and Productive Film Set Starts at the Top

James credits Dune’s director and co-writer, French-Canadian filmmaker Denis Villeneuve, for the wonderful experience working on set. Villeneuve has also directed Blade Runner 2049 and Sicario, among others, and has helmed Dune: Part Two, which is slated to hit theaters next March following a delay from this autumn.

James also highlights cinematographer Greig Fraser. His curriculum vitae is remarkable, having worked on The Batman, The Mandalorian, Rogue One, and nearly 50 other projects since 2000.

Villeneuve often works with the same heads of departments, including Fraser, across multiple projects, which James credits for a sense of camaraderie, cooperation, and security on set. “They are secure, talented, calm, giving, and good people,” James says.

James’ strong working relationship — and friendship — with Fraser pays dividends in her work. Fraser has a rich background in stills photography, a common theme among the world’s most talented cinematographers, so he and James regularly “talked shop” on set. There was a dialogue during the production.

Beyond mutual respect, Fraser also understood what James needed to do her job, and ensured that she had the opportunities required to capture the necessary images.

“Greig Fraser is a genius and bends natural light unlike anybody I’ve ever met before,” James says. “He’s really in touch with the light in Wadi Rum, Jordan,” James says. The harsh environment was one of the primary filming locations for Dune, and it posed challenges to the filmmakers and James alike.

Fraser relies heavily on natural light, so he uses a lot of reflectors and screens to control and bounce natural light on set. The resulting scenes are stunning, and, unsurprisingly, given Fraser’s background in still photography, they could stand up on their own as individual still frames.

“[Greig] walks around set with his camera, and he’s very in tune with stills and was a really big advocate for me as well. [Directors of photography] are usually where I get info to match my shooting, but we’re doing different things,” James explains.

“However, Greig was very interested in what I was doing, and so I was sharing imagery with him throughout. And again, he was very generous with me. Obviously, what I’m shooting on these sets, especially when I’m shooting the scene, is their art. I’m capturing the moments within it, but it’s their lighting, it’s their set, it’s their world that they’ve created that I get to be a guest in and just pull moments from. And that is its own art, and I don’t want to take away from that.”

The photographer also says that she thinks there were times when Fraser was testing her on set. “There was one moment where we stood on set one day and he’d just finished lighting and I was nearby. He asked, ‘What do you think?’ I said, ‘What? I don’t know, I’m just watching you. You’re the genius,’” James explains. “But the fact that he would even ask that question was amazing. I tell him, ‘I love this. But I don’t understand what you did there.’ So, he explains it. It was a really lovely collaboration.”

Finding Moments

Given that modern film creation is so fast-paced, James says that it was crucial that Fraser respected her work and made sure she had what she needed throughout production.

“I think that Greig’s respect for stills was really helpful. If I needed something, if there was a moment that I wanted to pull Timothée [Chalamet] or Rebecca [Ferguson] aside and get something that wasn’t in scene, I could do that,” James says.

Even though James agreed with PetaPixel’s assertion that it is almost always obvious when a director or cinematographer has a background in still photography, she believes that she could never do their job.

“My brain works in moments, and I’m really good at finding moments, but the idea of having to create a whole storyline that connects all the moments in motion, it just blows my mind,” James says. “That’s on a whole other level.”

She also says that it is rare to be on set and be able to work with people who do understand still photography.

“I’ll be on a set, and filmmakers will look at me and go, ‘Did you get great stuff of that scene?’ I’m thinking, ‘What do you think I got of that scene that works in a still.’ I’m still not quite sure what they think I’m going to get,” James laughs. “That happens a lot.”

“To work for people like Denis and Greg, who truly do understand still imagery and how different it is, it’s incredibly helpful to the job.”

That said, James emphasizes how critical it is to understand the overall, larger story that a movie is telling when finding those individual moments on set and crafting a photographic narrative. While each of her images could stand independently, they fit together as parts of a larger whole.

“Obviously, so many people have read Dune, so the movie is a bit different. But I have to approach it as though someone hasn’t read the books,” James says. She needs to capture moments of characters and places that fit the overall story of the movie and how each character develops throughout the larger narrative.

But of course, a significant challenge to doing this is that the film is not shot in order. A scene early in the production process may be from the final act of the movie, for example.

“I look for imagery of characters that I know lead us in certain directions. I have to understand the development of these characters to be able to know what to look for,” James explains. “I have to pick and choose my battles on set, though, because I don’t have complete, full access. For me, it’s picking and choosing the key moments that I can use. I don’t like to take photos just for the hell of it, [but] hat was really hard on Dune because everything is so beautiful.”

“My job requires an understanding of who the characters are, where they’re going, what their importance is, and how I want to show all that to an audience that doesn’t know all the details and being very selective in that,” James adds.

Storytelling and Art Versus Marketing

Given that Dune was shot in spectacular locations against beautiful backdrops and with actors dressed in intricate outfits, it can be a bit difficult to remember that, ultimately, Chiabella James has been hired to perform a specific job — helping movie studios sell a film.

Like all commercial photographers, she must always serve the client. That doesn’t mean that the results can’t be artistic and personally meaningful, but it does mean that there are specific images on set that James must execute.

“I rely on information from people in charge because there’s a thousand ways you could shoot any one thing. Even though I was raised in this kind of photography, everyone comes from different backgrounds. I was raised with unit stills, so the client has always. Been my first and foremost, just because that’s kind of what this niche is,” James explains.

“And it took me a long time to figure out my own style. On the other hand, I have colleagues whose history is photojournalism, so they come up with a journalistic style because that’s where they come from.”

“I sometimes find it difficult to know what people will want from me. I absolutely rely on the marketing team [for a movie] to figure out what their strategy is. The more I can get from them, the better. That information is key. But you don’t always get it.”

Chiabella James says that on Dune, while she was expected to get certain shots for marketing purposes, people were very receptive to her more artistic images and cultivated an environment of creativity. Unfortunately, not every film set is like this.

Developing a Unique Style When Your Dad is a Photographer

“I think rebelling against my dad has informed my style,” James explains.

However, she adds, “I take great pride these days when somebody looks at an image of mine and goes, ‘Wow, that’s a David James.’ That’s great. I love it because it doesn’t happen that often.

“He and I joke all the time that we had a little photo competition once, just on an iPhone, I think, and there was a leaf on the ground, a pretty autumn leaf. We both took a photograph of it. I like to off-center things, just maybe the quirkiness of my brain. I don’t see the world in balance. I like to throw things off into a little corner and leave a whole bunch of dead space,” James explains.

Her dad tried to do something similar with his composition, but he couldn’t do it. “He told me, ‘That’s your thing. That’s just not mine at all.’ It was just a funny moment we had. We come from a different headspace and different viewpoints, which when we’ve worked together in the past — we did four or five films together as a duo — it was really cool because we photographed the same scene and came away with very different imagery. This has also shown me that every photographer will take on any job differently.”

James says that if another photographer had shot Dune, the images would be different. “Yes, it’s going to be the same scenes and the same overall collection of images, but the angles and moments we look at, we see them differently.”

Celebrating Everyone on a Set

Chiabella James does this job not just because she’s good at it — although she is — and because it is how she makes her living, but because “this is home for me.” It is all she’s ever known. “I was raised by camera, grip, and electrical teams who allowed me, as a kid, to be around them. It’s my home, and they’re my family. They’re the reason I like going to work every day.”

Throughout Dune Part One: The Photography, this kinship that James feels with everyone on set is immediately evident. Of course, there are many photos of the film’s stars on location, in character, and as themselves, and there are photos of Villeneuve directing and Fraser setting the scene. There are photos of the people whose names are on movie posters, which James also shot.

But there are also photos of the people whose names even the film’s most ardent supporters and fans will never learn, but whose contributions and role in helping to create the final movie are no less vital.

“I think most photographers want to work in film because they love film,” says James. “Not that I don’t, but it wasn’t a motivating factor. This traveling circus is my family. And it probably affects how I photograph them. I love taking photographs of the crew and showing them at work and capturing those moments.”

A photo editor once told James that her behind-the-scenes photos were “very different” from any he had seen. “There’s a real affection for me towards what’s happening around me as opposed to just the film I’m photographing, even though that is the commercial priority,” James says.

![]()

James’ book, and her work at large, is a visual love letter to everything that happens on set and all the people who help make the movies so many people love.

“While we couldn’t make the movie without [the actors], you also can’t make the movie without the camera truck driver, for example. You can’t make a film what it is without all the moving parts that get you there. And I think everyone has their moments.”

Chiabella James is a professional photographer who works as a unit photographer on major motion pictures. She also does event photography and has been working on more personal projects lately due to the ongoing actor’s strike. Her work is available on her website and Instagram.

James’ new book, ‘Dune Part One: The Photography,’ is available from bookstores now. It includes a foreword by executive producer Tanya Lapointe, a preface by actor Rebecca Ferguson, and an afterword by Brian Herbert, the elder son of late and celebrated Dune author Frank Herbert. In Brian Herbert’s afterword, he immediately notes that while his father was best known for his incredible writing, he was also a professional photographer.

Image credits: All images © Chiabella James