![]()

I have always admired Sigma. It wasn’t regarded in the same league as it is today for its lenses until the Art series came out, but Sigma’s digital cameras have always been singular in design and purpose. The family-owned company has never been afraid to try something new, and honestly, that’s something we need to see a lot more of in the photography world.

The Foveon cameras are certainly the most notable example of Sigma’s fearlessness; they’re also the only digital cameras the company made before the fp series. The unique sensor design of the Foveons — which includes both Foveon X3 and Foveon Quattro — has always relegated them to niche status.

![]()

They aren’t fast cameras to use, they’re terrible in low light, their dynamic range is limited compared to Bayer sensors, video is non-existent, and processing X3F (Sigma’s version of RAW) files in Sigma Photo Pro is a dreadful experience. But, under ideal circumstances, the results are undeniably impressive.

![]()

Sigma’s commitment to niche camera products is arguably its greatest strength. The company is also one of the most transparent and friendly in the digital photography industry. It’s impossible for me to feel anything other than pure admiration for a company that is unafraid to take daring risks, even if it means the results fall short of perfection.

In 2019, the company unveiled the Sigma fp, the smallest full-frame digital camera ever made (and remains so to this day). Boxy in physical design but bold in ambition, the Sigma fp features a 24.6-megapixel BSI Bayer sensor, while the Sigma fp L sports a high-resolution 61-megapixel BSI sensor.

Both utilize fully electronic shutters and the Leica L mount. The cameras can record 4K uncompressed 8-bit CinemaDNG internally to a UHS-II SD card or output 10- or 12-bit CinemaDNG to an external SSD via its USB-C port. Both models also support 12-bit Blackmagic RAW or ProRes RAW recording via HDMI to a Blackmagic Video Assist 12G or Atomos recorder, respectively.

![]()

The Sigma fp also incorporates tons of features rarely or never seen before in a consumer stills camera — three 1/4”-20 threads, “Cinemagraphs,” distinct UI for stills and video, timecode support, cinema-style false color (called EL ZONE), Atomos Cloud support, Frame.io support (with H.265 proxy upload), a Director’s Viewfinder to simulate different angles of view on popular cinema cameras such as Arri Alexa and RED, a screenshot feature, a composite mode for a super-low effective ISO 6, uncompressed RAW video, direct-to-SSD recording, and many other cool and unusual functions.

The Director’s viewfinder feature alone makes this camera a very compelling alternative to traditional Director’s viewfinders, which naturally cannot take photos or video or precisely simulate dozens of camera models. If it had been around when I was shooting films regularly, I would have certainly purchased the fp L along with the very nicely designed Sigma LVF-11 LCD loupe for that feature alone.

![]()

The Problem

From eschewing a mechanical shutter and viewfinder to offering 12-bit uncompressed RAW output to an external SSD, the fp cameras are anything but ordinary in design or intent. But some of those decisions are also responsible for the cameras’ shortcomings.

Let’s discuss some areas where the fp and fp L fall short. Designed to be as small as possible, Sigma eliminated a mechanical shutter. In doing so, the cameras rely entirely on their electronic shutters. While electronic shutters are often capable of much faster speeds than mechanical shutters (the Fujifilm X-H2 and X-T5 go up to 1/180,000 sec, for example), they also typically take much longer to read out.

While a mechanical shutter has a readout speed of around 1/250 second, electronic shutters often fall between 1/10 and 1/40 second. This means moving subjects will warp as the sensor reads from top to bottom — cars, someone jogging or running, and moving people or animals are a few examples. Severity depends on the readout speed, but the final image will result in the bottom of the subject being in a different place than the top relative to its motion across the frame. Electronic shutters can and often do exhibit slight to severe banding under many types of artificial lighting, as well. Like the distortion of moving subjects, this becomes more prominent the slower the sensor readout is.

Further exacerbating this obstacle is that larger sensors tend to be much slower than smaller ones — I emphasize “tend” because more resources are poured into full-frame sensors and smartphone sensors, which is why there were five full-frame stacked sensor models on the market before a single APS-C or Micro Four Thirds body. Higher-resolution sensors also take longer, as they have more lines to read. The only exception here, of course, are stacked sensors, such as those in the Nikon Z8 and Z9 or Sony a1, which can be fast enough to match or nearly match the readout of a mechanical shutter.

The Sigma fp cameras contain full-frame sensors, which, in terms of the various sensor sizes on the market, are on the large side — only the 44×33 and 54×40 medium format sensors are larger (and the Leica S’s 30x45mm sensor). Since they are not stacked sensors, this means the readout speeds are pretty slow — somewhere around 1/15 second (14-bit) and 1/30 second (12-bit) with the Sigma fp, and 1/15 second (12-bit) and 1/10 second (14-bit) for the fp L. That is seriously limiting for both cameras, especially if you want to shoot 14-bit DNG raw files, which is certainly ideal for a full-frame sensor. It effectively makes the cameras unusable for anything but relatively static subjects (portraiture, landscape, product, studio, etc.).

Other shortcomings include the lack of a built-in EVF, no in-body image stabilization (IBIS), a fixed-screen, no integrated hot shoe, limited battery life, no internal LOG profiles, no 10-bit H.265 video, focus peaking and zebras can’t be turned on at the same time, no way to control ISO with the dials, menus lack touch-sensitivity, no option to power the camera when recording out through USB-C, and no HDMI pass-through when using the EVF. The fp is also not equipped with phase-detection autofocus, though the fp L is.

The Big Solutions

Let’s address the most prominent issues first.

Perhaps the most outstanding deficiency is the lack of a mechanical shutter. Given that the Sigma fp L, in particular, is more of a stills-oriented camera — the sensor is an all-around poor option for video — the camera desperately requires one. There are two solutions. The first is a stacked sensor. We can pretty much cross off this one for the next five years or so, as the cheapest stacked full-frame sensor camera on the market is the Nikon Z8 at $4,000. The other solution (outside of using a global shutter which only entered the realm of possibility very recently) is relatively simple: only put a rear curtain shutter in the camera. This is precisely what the Sony a7C II and a7CR do, as well as the Canon R8 and R100. This has very few limitations over a shutter with both front and rear curtains but does save space.

Then there’s the non-tilting screen — again, the only solution is to design it with a tilting screen. But Matt, you ask, won’t all this increase the camera’s size dramatically? I would argue that it would not — at least not meaningfully so.

Here are side-by-side size comparisons between the Sigma fp L (same dimensions as the fp) and the Sony a7CR, which includes a mechanical shutter, 7-stop IBIS, a tilt screen, an EVF, and even the same sensor. The Sony is 1mm taller, 11mm wider, and 18mm thicker — though the latter is due primarily to the pronounced grip on the Sony. Take that away, and the difference is a few millimeters at most.

Let’s compare it to a camera that doesn’t have an EVF but does have a mechanical shutter, 5-stop IBIS, and an articulating screen: the Sony ZV-E1. The Sony is 2mm taller, 8mm wider, and 9mm thicker — the latter again due to the Sony’s protruding grip, without which it appears they would be identical. Notably, both of these cameras also have hot shoes, and the ZV-E1 includes a substantial built-in mic.

I will also show that a tilt screen would not increase the size at all: third-party manufacturers have created screen modifications allowing users to install a versatile tilting screen with zero change in the camera’s dimensions. If a user at home can modify their digital camera with a $250 kit, a company like Sigma can surely figure it out.

![]()

Now, there is one big difference between the Sigma fp cameras and these Sony models — the fairly sizable (at least compared to the size of the camera) heatsink. This is probably the main reason the fp body is nearly as large as the a7C and ZV-E1 cameras. It’s certainly not a superfluous feature; when shooting video, the camera is processing and pumping out a lot of data. Some older Sony models would overheat quickly just shooting 8-bit 4K XAVC at 100 Mbps, so you can imagine the cooling necessary for recording raw video.

There are several potential options here, in my mind. Firstly, a non-fixed screen alone helps — when I had a Sony a6500, it would record at least twice as long just by having the screen pulled away from the body. But it could also allow Sigma to integrate some kind of ventilation behind the screen. Additionally, an articulating flip-out screen would open the door to an accessory cooling fan, such as the Fujifilm FAN-001 available for the Fujifilm X-H2s, X-H2, X-S20, and GFX100 II.

Implementing lower bitrate compressed video (whether RAW, ProRes, or H.265) would significantly reduce the heat generated compared to uncompressed CinemaDNG. The biggest niggle concerning the heatsink, however, is IBIS. Cooling a sensor that’s not locked in place is much more difficult. So, practically, IBIS may be very difficult to integrate effectively without a marked increase in volume.

Now, I’m not saying that none of these changes would increase the size of the camera — they probably would a little. But the critical question is if the many advantages are worth a few millimeters in each dimension. For me, they certainly would be.

Solutions to Other Flaws

Some other solutions to the camera’s flaws are obvious: install LOG profiles and internal 10-bit H.265 and/or ProRes recording, make the screen touch-sensitive, allow ISO control to be customized to controls, etc. Phase detection autofocus will undoubtedly appear in any future models, so that is of no concern to us. Others are a bit trickier, and the solutions are subjective, but here are mine.

![]()

The EVF and hot shoe are next to address. Here, we can solve four problems in one (I’ll get to the fourth one later). Build a hot shoe into the top panel with electrical contacts for an external EVF — the excellent Blackmagic Design EVF is a good example. This gives us a hot shoe, moves the EVF to a more logical location that doesn’t interfere with ports, and frees up the HDMI port to actually be used. Also, not only does it allow the use of flash without an awkward, bulky accessory (the HU-11 Hot Shoe Unit), but it gives video users a place to easily mount an external monitor/recorder.

You might say, based on the current design, that there is no room for a hotshoe. To that, I would say: integrate the Cine/Still switch and Power switch into one with three positions — Off, Cine, and Still. Switching to either cine or still from the off position would simply power the camera up. Boom, now there’s plenty of room. There’s not a single reason to have those as two separate switches anyway.

![]()

RAW video needs some attention, too. This is a great feature, but in its current implementation of uncompressed DNG, it presents numerous problems. Most notably, the camera can only record 8-bit internally, and uncompressed CinemaDNG files are enormous. This is a limitation of the UHS-II SD, which maxes out at a guaranteed 90MB/s with V90 cards. The solution? The easiest would be to add CFexpress Type-A support alongside UHS-II SD, as Sony has done on its recent cameras. This doesn’t change size in any way but would allow the camera to write 4K RAW files to CFexpress A cards while still allowing the utilization of cheaper SD cards. The fp’s highest data rate — 4K UHD 12-bit CinemaDNG at 29.97 fps is 2,980 Mbps, just under the 400MB/s that VPG 400 cards, like the Lexar Gold Series, are certified to support. Additionally, Sigma could probably include built-in SSD storage, such as in the Leica M11/M11-P, without much of a size sacrifice. This would allow for recording of pretty much any format.

The second option, which is certainly not mutually exclusive with the first, is to incorporate Blackmagic RAW (BRAW) or ProRes RAW for internal recording — the Nikon Z8 and Z9 have internal ProRes RAW, for example, so it is clearly possible. And Blackmagic has intended BRAW to be a sort of license-free open standard, based on what I understand. The Blackmagic RAW SDK is even free and publicly available.

![]()

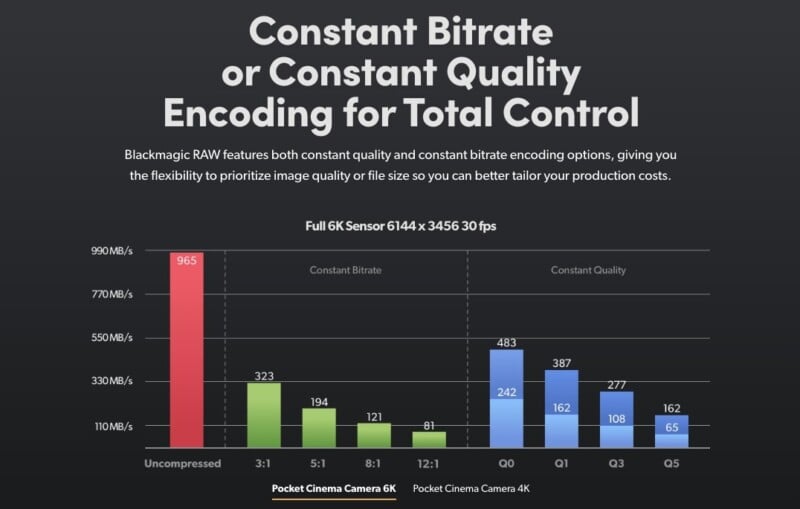

Either BRAW or ProRes RAW would allow for significantly reduced storage requirements and future-proofing for resolutions greater than 4K, which would undoubtedly exceed the VPG 400 certification in CinemaDNG. As you can see here, any VPG 400 certified CFexpress Type A card could reliably record 12K BRAW at 8:1 and higher or Q5 compression, as well as any flavor other than Q0 in 6K DCI (and most likely, VPG 400 cards could handle 6K Q0 given the peak of its variable bitrate would rarely, if ever, be hit for long durations).

![]()

Battery life (the fp cameras are CIPA rated for 200 shots) doesn’t have many solutions aside from a more efficient processor or more advanced battery design. One option, of course, is to offer a battery grip — like Blackmagic does — which may or may not be desirable, but having it as an option, especially for video users, would be nice either way. However, the more significant issue is that, when using the USB-C port for recording to an SSD, there are zero alternatives to power/charge the camera aside from a dummy battery with D-Tap adapter. This is rather cumbersome and inelegant for filmmaking setups, and options are scant on the market (the Bescor is the only one I can find at B&H or Adorama).

A second USB-C port would be the ideal solution, as it can also be used for many things other than power. Where would it fit? Well, if the hot shoe were integrated into the camera body, the six communication pins for the HU-11 Hot Shoe Unit that sit above the current USB-C port would no longer be needed. It could also replace the microphone/headphone port, as that would still function with a simple USB-C to 3.5mm jack adapter — doing this could allow Sigma to upgrade the micro-HDMI port to a full-size HDMI port.

As you can see, if you removed the flash interface and swapped the 3.5mm input for a second USB-C port, there would be plenty of room for a full-size HDMI (or possibly SDI?) port.

Flawed Cameras with Huge Potential

The Sigma fp and fp L are two of the most frustrating yet exciting cameras released in the past few years — frustrating because of the great many limitations they present in so many ways, but exciting because of what they represent: something different. They are packed with tons of features you won’t find in other hybrid cameras (or in any cameras), but like the Foveon cameras, they embody a decidedly alternative approach.

![]()

And that is why I care so much about what future models could be. Even if the cameras increased in size a little — which no one would actually notice in practice — they would still be singular models in a sea of technology that generally avoids embracing out-of-the-box design.

These novel cameras have the potential to retain everything that makes them unique while also becoming extraordinary. And that’s what I want to see.

Image credits: All photos, unless otherwise noted, via Sigma.