Since the International Energy Agency’s inception in 1974 following the world’s first major oil crisis, it would be an understatement to say that the energy industry has gone through a lot of change. And yet, even as it celebrates its 50th anniversary, the IEA has found a way to reinvent itself to maintain its influence on global affairs.

That relevance was on show when the IEA hosted an event last week to kick off its anniversary celebrations. Leaders of the European Union, Germany and India were among those who praised the institution’s work through the years, even as it has had to change its focus.

The IEA “has been able to profoundly shift its mandate,” said French President Emmanuel Macron. “From an agency dedicated to managing strategic oil reserves, it has now become a global hub for debate and collective action to meet the challenge of the energy transition.”

Energy security remains the IEA’s biggest directive. When it was founded, that meant ensuring rich countries had reliable access to fossil fuels and promoting energy efficiency. Today, it means managing a global energy transition away from fossil fuels in as orderly a manner as possible.

It’s not the only change. Fifty years ago, the IEA only had 17 countries as members. Today, there are 31, including most European nations, and another five in the process of becoming full members. There are a further 13 association countries — most notably Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and South Africa. In total, these countries account for more than 80% of the world demand for energy.

This is why the IEA no longer solely focuses on concerns of western countries, but also on issues such as energy access in developing economies. It’s one reason the IEA has in recent years produced reports on clean cooking and energy-efficient cooling, in addition to hydrogen and carbon capture, which are currently more on the minds of rich nations.

Throughout its history, the IEA’s work hasn’t always made front-page headlines, but continues to feature at the highest levels in government reports and investment decks. The World Energy Outlook, which has been published annually since 1998, is often cited as the reason for deployment of certain policies or for helping shape investor sentiment on particular industries.

Kate Hampton, chief executive officer of the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, a multibillion-dollar endowment that invests in clean-energy projects around the world, highlighted the agency’s “extraordinary leadership role” in recent years. “It’s been playing internationally on showing the direction of travel,” she said.

That wasn’t always the case. In the early 2000s, as governments started to think about a transition to renewables, the IEA’s analysis of clean energy wasn’t taken seriously. It kept missing the scale of deployment and the fast-reducing price of solar and wind power. It’s one reason why the United Nations created the International Renewable Energy Agency in 2009, with its headquarters in Abu Dhabi.

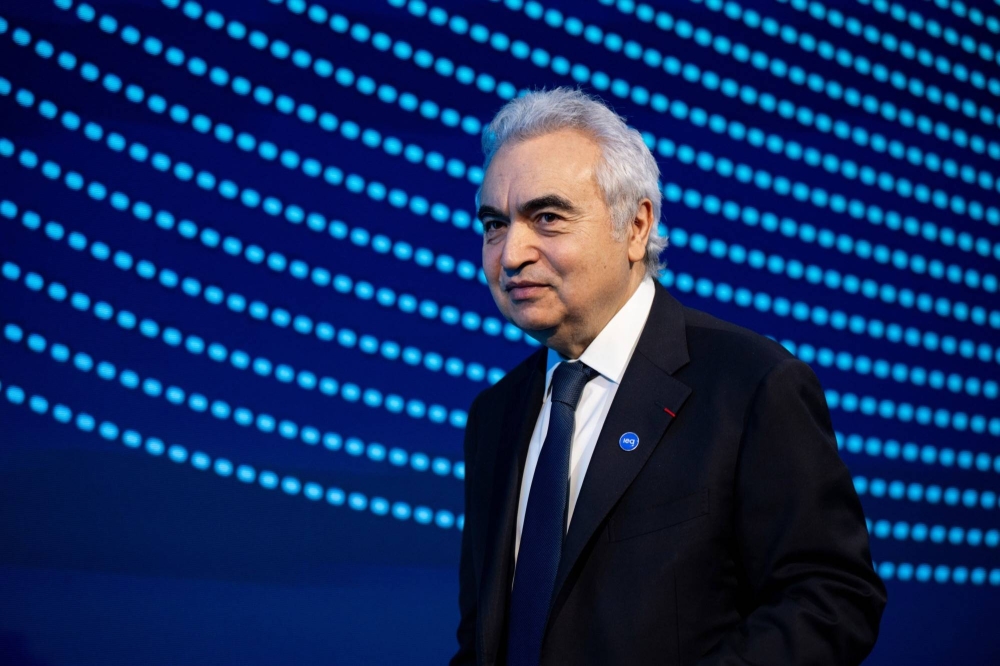

That threat spurred Fatih Birol, an economist who was appointed as the IEA’s executive director in 2015, to push the IEA to think bigger. It’s what led to both the massive expansion in the IEA’s membership and its added focus on clean energy.

Yet it also happened when there was increasing polarization between people who mainly think about energy and those who mainly think about climate, according to Birol. It’s no longer just the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries that skewer IEA’s forecasts. There are other critics like Robert McNally of Rapidan Energy, which offers competitive energy forecasts to the IEA. McNally says kowtowing to climate demands is weakening the IEA’s ability to do its first and foremost job: ensure energy security in the world.

But the IEA has been able to repel those criticisms because of three key reasons, according to Birol. First, it collects high-quality data directly from governments on energy production and consumption. Second, it employs an army of number-crunchers, many with PhDs, to analyze those numbers. And, finally, its major analyses are widely peer-reviewed by those in academia, government and industry, before they are published. That’s what gives the IEA’s analysis the credibility and influence that it continues to enjoy.

In the end, however, the buck stops with Birol’s bosses who are energy ministers of the IEA’s member countries. And they reaffirmed last week that the IEA’s focus must be ensuring global energy security, marshaling the energy sector’s fight against climate change, and boosting global financial flows for the clean energy transition, especially in developing countries. That should keep it busy for at least a few more decades, before it has to think about reinventing itself yet again.