New Delhi: In its monthly alert for the month of August, the country’s apex drug regulator said it found 59 medicines, some of them well-known and marketed by top pharma companies, were found substandard or fake. Against the backdrop of flak over supply of drugs and cough syrups—associated with serious adverse events including deaths—to other nations, this, understandably, triggered outrage.

But those batting for patients’ rights and better quality of drugs point out that India has larger problems to deal with including the lack of effective mechanisms to guarantee a national recall of such drugs.

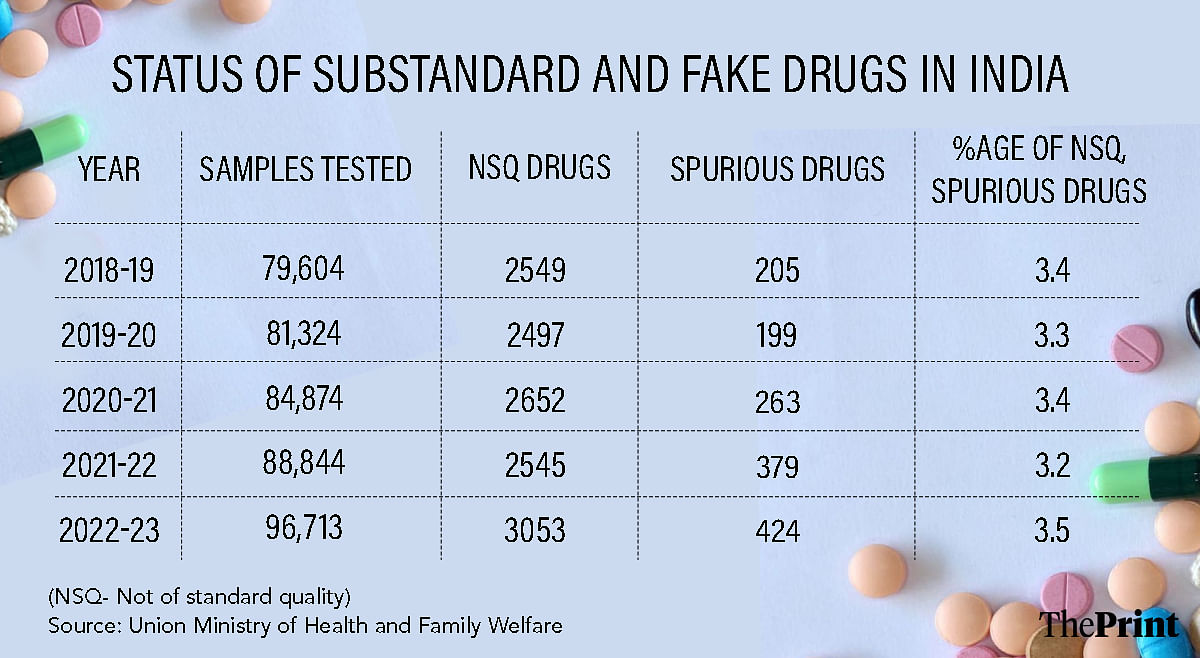

A close look at government data showing the proportion of not of standard quality (NSQ) or counterfeit drugs reaching the Indian market reveals that this number hovers between 3.2 to 3.5 percent.

For instance, in 2022-23, the last financial year for which data on NSQ and fake drugs is available, of the 96,713 samples tested, as many as 3,477 or 3.5 percent were found problematic. In 2018-19, this figure was 3.4 percent.

In the latest list issued by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) in August, 54 drugs were declared NSQ and another 5 fake.

NSQ drugs are those that fail to meet national or international quality standards, thus being ineffective or less effective, while fake drugs are those made by someone other than the authorised manufacturer, and are designed to look like the genuine product; also, often unsafe or dangerous.

Though the list included names of only manufacturers, and not marketers, it was pointed out that they included brands (CDSCO publishes names of drug brands found NSQ or fake) by pharma giants including Sun Pharma, Lupin, Torrent, Glenmark and Alkem, among others.

On their part, many of the companies were quick to disassociate themselves with the episode saying the flagged batches were fake and not their products.

The Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance, a network of the country’s top 23 drugmakers, too issued a statement alleging misrepresentation and deliberate distortion of facts by select media outlets vis-a-vis the alert.

“The misleading coverage irresponsibly interchanges the terms NSQ and spurious and wrongfully implicates genuine manufacturers in the production of spurious drugs,” IPA secretary general Sudarshan Jain said in a statement issued on September 29.

Manufacturing spurious drugs is a serious criminal offence that threatens public health, he said, adding that the outrageous linking of spurious products with legitimate manufacturers has severe reputational and financial impact. “Moreover, this tarnishes India’s reputation as a reliable supplier of medicines on a global stage. It is critical that a clear distinction between NSQ and spurious drugs is made,” the statement underlined.

Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) Rajeev Singh Raghuvanshi, who heads the CDSCO, said Wednesday that publication of nearly 50 samples found of low quality was part of a routine process. “Majority of these drugs failed on very minor parameters which could have negligible health risk,” he told reporters on the sidelines of the Biopharmaceutical and Life Sciences Summit organised by the Confederation of Indian Industry.

Also Read: Inside India’s shadow pharma industry — dingy drug units, cash payments, poor inspection

Ineffective drug recall policy

Despite rising demands for laws mandating recall of drugs found ineffective or unsafe, the norms revised by the CDSCO in July this year on drug recall were in the form of guidelines, lacking any legal backing.

These norms, like the previous one released seven years ago, put the onus of recall on manufacturer and the marketing company.

The guidelines define two types of recall: voluntary when it is initiated by the licensee as a result of abnormal observation in any product quality during periodic review or investigation of a market complaint or any other failures; and statutory when it is directed by drug control authorities but fail to elaborate how statutory recall would be affected.

“We don’t have a law or a statute that mandates a recall. It’s a complete eyewash. I don’t understand the point of testing samples if those that fail are not being recalled and patients who consume these drugs are not being informed about their failure,” Dinesh Thakur, a public health expert focused on improving health policy in the US and India, told ThePrint.

Thakur, who co-authored the book The Truth Pill: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India, termed it a complete abdication of responsibility of the regulator.

Prashant Reddy, a lawyer and co-author of the book, too emphasised that the government should first conduct a national recall of all batches of the drugs from the market and put on hold the manufacturing licences of these companies.

“The government should then conduct and publish the root cause analysis for each drug that has failed, identifying why exactly the drug failed quality testing. We need to know whether the drug failed because it was poorly formulated by the manufacturer or poorly stored as it travelled through the supply chain,” he explained.

Depending on the cause of failure and culpability of the manufacturer, the government needs to prosecute the manufacturer as per the law, he added.

Reddy also asked, what steps are being taken to inform patients who have bought the drugs that these drugs are not effective, adding that there is no system in place to tackle these issues.

But Raghuvanshi maintained that in cases of NSQ and fake drugs, the regulator gives recommendations for prosecution or for administrative actions depending on how serious the noncompliance is.

Asked how the regulator ensures prescribing doctors and the public are aware of drug batches declared NSQ or spurious, he said the media had been doing a “good job”.

“Our drug alerts are put on our website every month and are in public domain..also over the last 6-8 months Press is doing a good job of reporting about these alerts,” he said.

But Reddy insisted that the government should clarify on the steps it is taking to withdraw the drug from the market. “Merely asking the companies to effect a recall is of no use,” he said. He also said authorities need to verify the recall and destroy the recalled batches.

What about FDC drugs?

Another major concern, said Malini Aisola, convenor of the patient rights group All India Drug Action Network (AIDAN), is that CDSCO drug alerts do not name the marketing companies of drugs found substandard even though liability of drug recall rests with both manufacturers and marketers.

In India, like in several other countries, major drugmakers contract the manufacturing process to smaller companies, while managing only the marketing and distributing parts. “We have no idea how many of the bigger companies are implicated because they are marketing these brands, their names simply don’t appear in the alert list,” Aisola said.

Also, while the proportion of NSQ and fake drugs has remained under 4 percent, it is not insignificant, she added.

“Moreover, statistics could be deceptive because samples tested for quality largely do not include FDCs (fixed dose combination drugs) which comprise over 40 percent of drugs sold in India as there are no norms in place to test their quality,” Aisola said.

FDCs contain two or more drugs in a single pharmaceutical form and many of these combination medicines available in India lack approval from the central regulator CDSCO and have been approved for manufacturing by states without showing adequate proof of safety and efficacy.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Antifungals sold as chemo, top hospitals’ staff involved — Delhi fake cancer drugs case chargesheet