Scientists in China have successfully cloned a rhesus monkey by providing the cloned embryo with a healthy placenta. The innovative technique could significantly increase the success rate of cloning, the researchers say.

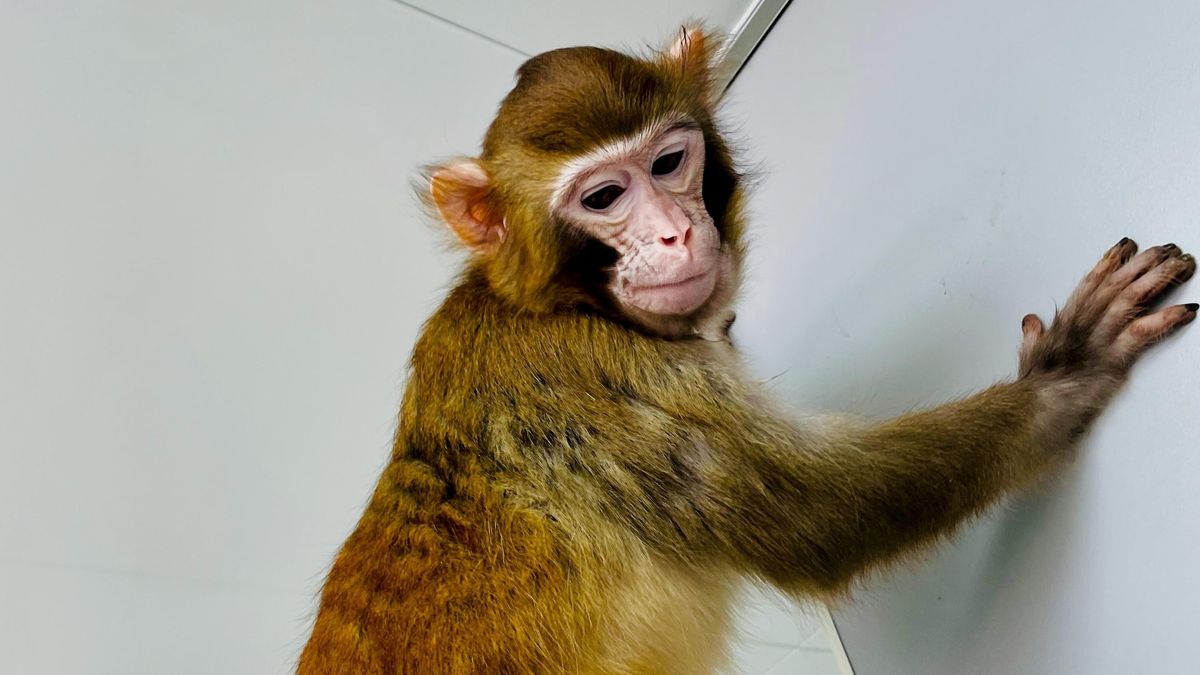

The monkey, named ReTro, is now three and a half years old and still “doing well and growing strong,” study co-author Qiang Sun, a primate neuroscientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology, told Live Science in an email.

Researchers have cloned rhesus monkeys before, but this is the first success using a method known as somatic cell nuclear transfer, which involves replacing the nucleus of a fertilized egg cell with a nucleus extracted from another individual’s somatic cells. (Somatic cells include every cell in the body except reproductive cells.) A previous attempt to clone a rhesus monkey using somatic cell nuclear transfer resulted in a live birth, but the infant died just 12 hours later.

Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), also called rhesus macaques, are commonly used in laboratory experiments and medical research because they are genetically very closely related to humans. Creating clones of these monkeys “can help us to obtain non-human primate models with identical genetic backgrounds and genotypes [to each other] in a short time,” Sun said. This would help researchers filter out any effects of genetic variation between models when testing drugs, for example.

Related: Scientists want to clone an extinct bison unearthed from Siberian permafrost. Experts are skeptical.

The successful cloning, which was described in a new study published Tuesday (Jan. 16) in the journal Nature Communications, is a step toward improving cloning efficiency in primates and other mammals, Sun said.

Scientists have used somatic cell nuclear transfer to clone a range of different mammal species, such as other monkeys, sheep (including Dolly the sheep), cattle and dogs. Most cloned embryos don’t survive to birth, however, often due to defects in the development and structure of the placenta. Between 1% and 3% of attempts result in a live birth using conventional cloning methods, according to the study, although the success rate is slightly higher in cattle (5 to 20%).

To overcome this problem, Sun and his colleagues replaced a cluster of cells that normally develops into the placenta from the cloned embryo with the same cells from a normal embryo. These cells, known collectively as the trophectoderm, formed a healthy placenta that provided the cloned embryo with nutrients and oxygen during development. The experiment resulted in the birth of a healthy male rhesus monkey in 2020.

“This approach significantly increased the success rate of cloning by somatic cell nuclear transfer,” Sun said, and it could yield “a higher number of cloned animals using a reduced number of oocytes,” or egg cells.

“As placental defects are commonly seen in all cloned mammal species, we anticipate that it might be applicable in other mammals and non-human primates,” Sun added.