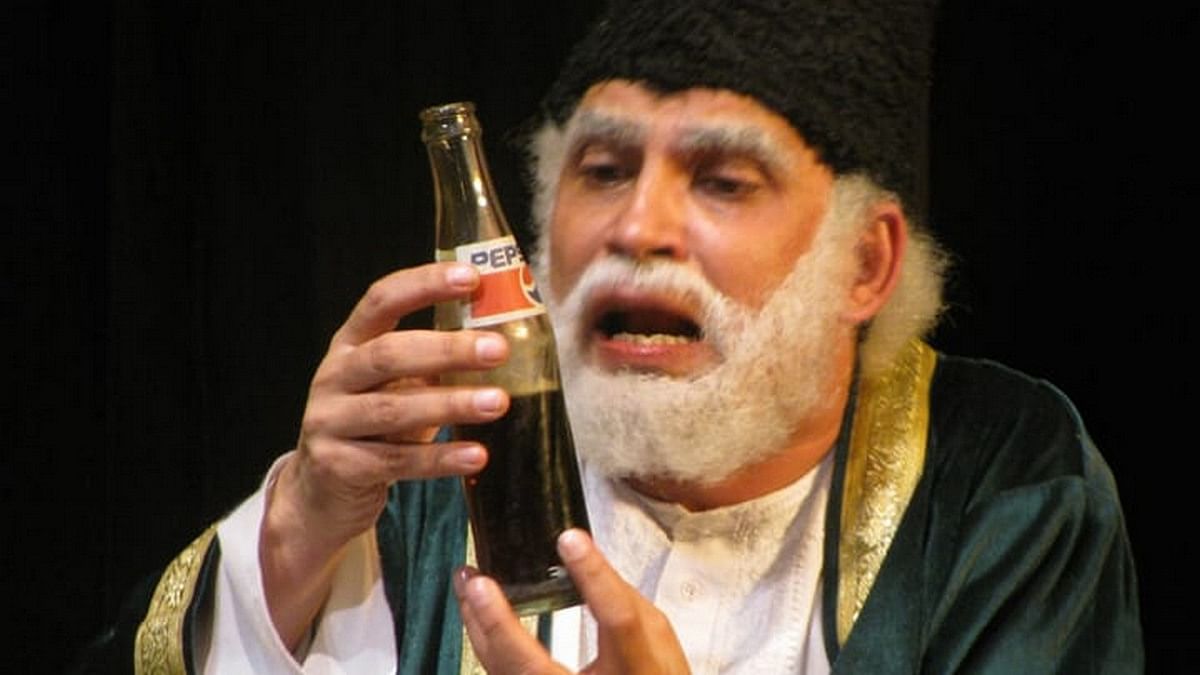

New Delhi: A dark stage lights up and the 19th-century poet Mirza Ghalib wanders in, dressed in a green velvet robe, white kurta-pyjama, and his signature tall cap. He’s searching for his way back to his haveli in Old Delhi’s Ballimaran. Over the next two hours, he transforms into a modern man—wearing a white T-shirt and Bermuda shorts, clean-shaven, and chatting with a friend on his iPhone about rubbing shoulders with Amitabh Bachchan and Shah Rukh Khan at the Anant Ambani wedding.

At the beginning of his quest to find the haveli, the Persian and Urdu poet encounters various characters, including auto drivers, an alcoholic, and a corrupt police officer. In one conversation, a driver asks Ghalib if he is from Bihar. Confused, Ghalib doesn’t understand what Bihar is. Another driver explains: “Arrey woh pull wala. Jaha pull paani mai beh jate hain” (The place where bridges flow away in water), referring to recent bridge collapses in Bihar.

A few months into his modern rebirth, Ghalib adjusts to the new world. He learns about technology, the internet, social media, and more. At his new house in Delhi’s Laxmi Nagar, he translates his poetry into modern lingo and puts out ads to become famous. In a phone conversation with a friend from heaven, Ghalib, who initially didn’t understand buses, autos, or mobile phones, shares his experience with “Instagrameen seva” (Instagram).

This reimagined, time-travelling Ghalib is the creation of M Sayeed Alam, a noted theatre director and playwright who has written over twenty plays in the last three decades. Alam’s satirical play, Ghalib in New Delhi, has been performed 589 times since 1997 and has evolved with each era.

Its latest version, recently staged at Little Theatre Auditorium Group in Delhi’s Mandi House, continues its tradition of providing sharp commentary on societal and political changes in India through Ghalib’s perspective. In 2024, Ghalib weighs in on everything from the NEET controversy and the arrest of Aam Aadmi Party leaders to inflation and Indo-Pak relations.

“This play is like a documentary. It is not a static play and always has some improvisation,” Alam told ThePrint. “We always incorporate current affairs in our performance and that’s what our audience expect from this play.”

Also Read: From Mahabharata to Mughals—a queer play uses Indian elements to break the ‘for-elite’ norm

Hitting the headlines

Ghalib, born in 1797, witnessed some of the biggest political upheavals in Delhi, including the rise of the East India Company and the British takeover after the 1857 uprising. He eloquently chronicled his observations and emotions, making him the perfect character for Alam and his troupe to bring back to life.

Since its debut in 1997, Ghalib In New Delhi opens with the poet’s rebirth at an inter-state bus terminal, from where he struggles to find his way to Ballimaran, his old haveli (now a museum). His conversations with various characters lead to hilarious commentary on contemporary society and politics, leaving the audience in stitches.

In the opening scene, Ghalib sits next to a woman selling paan and learns about modern-day inflation. When he asks for the price of paan in aana, a former currency unit, the woman humorously attributes her ignorance to the concept of ‘Beti Padhao’ not existing in her youth. She then converts the amount on her phone and demands 160 aanas. Shocked, Ghalib retorts: “160 aaney mai acha khasa murg musalam naseeb hojaye” (You could get a whole Murg Musalam for 160 aanas).

The play is peppered with references to current affairs, including the arrests of AAP leaders Manish Sisodia and Arvind Kejriwal, the Patanjali case, Indo-Pak relations, and the number of students getting full marks in NEET. When a policeman asks Ghalib to go to Pakistan because he looks like a troublemaker, another character points out that the airport is out of commission because “waha ki chhat gir jati hai” (the roof falls down there), alluding to the Delhi airport’s T3 terminal collapse.

Throughout the play, the reincarnated Ghalib grapples with Delhi’s linguistic quirks. When people mispronounce his name as “Galeeb”, he emphatically corrects them, screaming in frustration, “Ghalib, Ghaaalib, Ghaaaaaalib.”

Also Read: Mirza Ghalib—the poet who took Urdu to the zenith of glory

Ghalib and governments

Back in 1997, Alam and his team decided to create a comedic marvel that merged two eras together. Through brainstorming sessions and collaborative workshops, they decided on a play that would resurrect Ghalib over and over to highlight the absurdities of the present day. Over the last 27 years, ‘Ghalib’ has not been a fan of any political dispensation.

So far, Ghalib in New Delhi has been performed during the tenures of five prime ministers and several governments.

“If you would have seen this play in 2004 or 2008, you would have said it was against the government. So whichever the establishment, this play has been a satire for them,” Alam said. During the tenure of the UPA government, the play was even staged in Parliament house, where they were asked to not remove political comments against the establishment.

In one scene, Ghalib recites an Urdu line: “Hazaar jawabo se behtar hai meri khamoshi” (My silence is better than a thousand answers), echoing a phrase once used by Manmohan Singh in Parliament.

“Unless satire challenges the establishment, it lacks depth,” Alam asserted.

At the 2024 staging, Ghalib aficionados and news enthusiasts alike found much to appreciate and chuckle about, like Sama, a 25-year-old photography student.

“The play didn’t lose momentum for even a second; every line, every dialogue was impactful and engaging. As someone who loves political commentary, it was so on point that I found myself clapping at every punchline,” she said.

For her, the play worked at both the intellectual and emotional levels.

“To quote Ghalib, ‘Dil hi to hai na sang-o-khisht, dard se bhar na aaye kyon’ (It’s my heart and not stones or bricks, why should it not be filled with pain),” she added.

The final scenes of the play, where Ghalib appears in contemporary attire, symbolise his timeless relevance, according to Alam. He pointed out that the real Ghalib embraced modern developments like trains, electricity, and apartment living, which witnessed during a trip to Calcutta, despite criticism from traditionalists.

“If Ghalib was alive today, he might have been critical of the current socio-economic and political system, but he would have adapted himself to the modern-day world,” said Alam.

“Mai andaleeb-e gulshan-e na aafrida hu,” Ghalib once prophetically said, describing himself as a nightingale of a paradise yet to be created.

Alam reflected that Ghalib’s poetry became famous despite the decline of Urdu, with fewer people writing, reading, and understanding the language. And his poetry also helped make others famous, including Jagjit Singh, KL Sehgal, Begum Akhtar, and Gulzar.

“He is a poet who lives in the sub-conscious of people,” Alam said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)