But the idea that routine and emergency medical services could become privatised and chargeable has rattled not just Sidhi’s residents, but also doctors, healthcare workers, patient rights groups, and even some within the ruling BJP. This has forced the Mohan Yadav-led dispensation to hit pause and re-evaluate the proposal amid fervent protests.

“If poor people like us are forced to pay even at a sarkari haspatal (government hospital), it is as good as signing a death warrant. We will simply die at the door of the hospital without money,” said Prabudh Bhainas, attending to his 19-year-old son Raja, who had been admitted to the Sidhi hospital after consuming insecticide in an attempt to take his own life. Bhainas, a farm labourer, earns Rs 400 a day.

What I earn is not even enough to buy nutritious meals for my family. How will we pay for hospital charges if they start asking us to pay?

Prabudh Bhainas, a patient’s father

The tender—which according to deputy chief minister and health minister Rajendra Shukla was aimed at augmenting government healthcare facilities and increasing the number of medical colleges in the state—was issued following a cabinet decision in March. The other districts chosen for privatisation are Katni, Morena, Panna, Balaghat, Bhind, Dhar, Guna, Khargone, Seoni, Tikamgarh and Betul—among the state’s poorest in terms of per capita income.

Amid intense pressure from different quarters, the government decided in the last week of November to re-evaluate the policy. But the chorus of dissenting voices continues to grow louder.

Also Read: Missing OPDs, 1 doctor per 10,000 in Faridabad, CAG audit shows grim state of Haryana public healthcare

MP govt’s plan

Madhya Pradesh’s health department had invited bids online in July from interested parties for setting up of medical colleges for 100 seats and upgradation of specified district hospitals.

The notice said that the government would “hand over the existing district hospital to the selected bidder on ‘as is where is’ basis”, adding that the selected bidder would be responsible for building and financing the medical college, augmenting the hospital, and operating, maintaining and managing both.

The cost of the proposed project was pegged at Rs 260 crore, which included establishing a 100-seat medical college and capacity augmentation of an attached 300-bed hospital, with a public-private partnership (PPP) model.

The plan, according to the tender document, was also to let private entities make 25 percent of the beds in the district hospitals payable. Additionally, according to announcements by top health policy makers, 348 community health centres (CHCs) and 51 civil hospitals in the state would have been outsourced.

It was in January 2020 that Centre’s think tank NITI Aayog had unveiled a plan for district hospitals to be handed over to private healthcare companies to run attached medical colleges on PPP basis. It was also endorsed in the Union budget that year.

The massive pushback, however, led the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government to rethink the decision.

“When we sat with all concerned stakeholders, we realised that the agreement we want to enter into with the private parties is a ‘service level agreement’, but there were various conflicts, such as who will monitor the services provided at these district hospitals and who will be accountable (for overseeing)?” a senior official in the state health department told ThePrint on the condition of anonymity.

“District hospitals are open to all and patients are provided free health services, but how will we ensure that patients are getting free treatment? Taking these points into consideration, it has been decided that the control over district hospitals will remain with the department.”

Commissioner of the Department of Public Health and Medical Education, Tarun Rathi, told ThePrint, “We are making changes to the earlier guidelines to protect the rights of the patients.”

The proposal is being reworked and is expected to be finalised in two weeks, he said. Present tenders that are still open for the 12 hospitals are being scrapped and a fresh tender with the new changes in its clauses will be issued.

The state’s deputy chief minister and health minister, Rajendra Shukla, clarified to ThePrint that according to the new proposal under consideration, district hospitals will merely serve as “teaching hospitals” for the new private medical colleges. This model, he said, will help the state government considerably increase the number of medical colleges in MP from 31 to over 50.

“This will take the total seats for MBBS in Madhya Pradesh to about 5,000, enabling the state to contribute to the realisation of PM Modi’s vision of creating 75,000 seats for medical students in the country.”

Considering that these private medical colleges will also have postgraduate students, the capacity of district hospitals will be augmented with the presence of specialists from these colleges, while the treatment to patients visiting district hospitals will remain absolutely free and continue in the same manner as it is presently, the deputy chief minister said.

According to Shukla, while the idea of handing over the district hospitals to private entities was to enhance facilities to reduce referrals and provide best possible treatment at the lowest level, the government later felt that there was apprehension within the political class and civil society. He said that the district hospitals also serve as “centres for various government programmes”, and are instrumental in “handling various medico-legal cases”.

Handing over the hospitals would essentially be giving away the presence of the government in the district to a private player. Thus, the government has decided to retain control.

Rajendra Shukla, MP’s Dy CM & Health Minister

The new developments follow a high-level meeting chaired by Chief Minister Mohan Yadav in the last week of November to deliberate the issue.

According to a government official, the decision to allow medical college students and faculty to train and treat at the district hospital is being considered as with new medical colleges, it may be challenging for the administration in newly set-up establishments to get patients and have 80 percent occupancy, as stipulated by the medical education regulator. The ventures should also be financially viable for private players, officials concur.

One of the options that the government now seems to be considering is that the patients at the district hospitals can be treated by doctors or specialists from the private medical colleges under Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB PM-JAY).

But for treatments that exceed the Rs 5 lakh cover provided under the health insurance scheme, the patient may be asked to pay the remaining amount separately, the official cited above added.

Also Read: Rural-urban transition, reforms in Municipal Act. How Modi govt plans to improve city governance

The big concerns

As the government still seems indecisive about the form the policy will take, apprehensions remain and those opposing the move demand that the policy makers first spell out the nitty-gritty details of the revised proposal.

In Sidhi, nearly 10 grassroot organisations, supported by Jan Swasthya Abhiyan (JSA)—the Indian chapter of the People’s Health Movement, which is a global network of health activists, civil society organisations and academic institutions in developing countries—took to the streets on 30 November, protesting against “any bid of introducing privatisation in government hospitals” with the slogan: “Haspatal bachawa, jiyau bachawa (save hospital, save life)”.

Umesh Tiwary, a local tribal rights activist, told ThePrint, “For the vast majority of the people here, the district hospital is the lifeline. For many who cannot even access maternal and child care at the poorly resourced CHCs and primary health centres, this is the only stop. It has its own share of problems, but handing it over to private players for profiteering is definitely not the solution.”

The Sidhi district hospital has a 100-bed maternal and childcare wing. While 83.6 percent pregnant women in the district deliver their babies in hospitals, 80.3 percent of them do so in public facilities, according to National Family Health Survey 5, indicating how significant the facility—along with 7 community health centres—is to the healthcare delivery landscape in the region.

About 20 deliveries are carried out there every day, six-seven of which are C-sections, noted Dr Diparani Israni, Sidhi’s civil surgeon-cum-chief medical officer.

But the acute shortage of anesthetists (the hospital just has one) means many urgent and critical cases are referred to Shyam Shah Medical College in Rewa, the nearest government-run tertiary care health centre. Others who can afford rush to bigger cities, like Jabalpur, Indore and Bhopal, or even Nagpur in Maharashtra. Over 30 percent of the posts for doctors are vacant at the Sidhi hospital, which is operating with just 25 doctors against 37 sanctioned posts.

Still, the district hospital is critical for healthcare needs here as the majority of the patients do not have paying capacity. There will be huge implications for patients if there are any bids to privatise the centre.

Dr Prateek Prajapati, surgeon at Sidhi hospital

This is a concern echoed by many public health specialists.

“Private partners, the experience so far has shown, are not interested in running public health programmes, like family planning, immunisation, and malaria, tuberculosis or AIDS control. They are interested in profit generating high technology investigations like diagnostics. Ultimately, all this will hit the people hard,” said Dr Antony K.R., public health expert and an independent monitor of the Centre’s National Health Mission.

JSA national convenor Amulya Nidhi said that the government had not even maintained transparency with respect to the criteria used to select the district hospitals for privatisation.

Sujatha K. Rao, former Union health secretary, underlined that PPP can become unfavourable for ordinary patients, especially if the ‘private’ dominates the ‘public’.

Where is the intent to serve the public? In a country where the private healthcare providers show no accountability and there is little supervision and regulation from the government’s side, letting district hospitals go into private hands will be disastrous.

Sujatha K. Rao, former Union health secretary

However, according to Dr V.K. Paul, member (health), NITI Aayog, the PPP model for the hospitals had been endorsed after due deliberation and in a bid to improve health services in underdeveloped areas. “I am not aware of the protests to the initiative in MP, but the model has been thought through and devised as a tool to improve health infrastructure in places where there are major challenges,” he told ThePrint.

But for doctors and other healthcare personnel in Sidhi, there is another key concern. “The government did not spell out the purpose behind the proposal. We did not know the terms of arrangement under the proposed PPP. We did not even know whether we will stay or go, and whether private owners will bring their own staffers,” said Dr Hari Om, a doctor at the Sidhi district hospital.

It is a relief that the project will be modified, but the government needs to clarify what it will entail for the public and existing staffers, he stressed.

The anxiety, however, is not limited to those within the healthcare system. There has been opposition to the move within the ruling party, too.

Rakesh Giri, BJP leader and former MLA from Tikamgarh, said that the district hospital in Tikamgarh serves as the sole healthcare institute, not only for people within the district, but also from the neighbouring Chhatarpur, and adjoining Lalitpur in Uttar Pradesh.

“The state government felt that since the (PPP) model is successful in Gujarat, it can be replicated in Madhya Pradesh, but people in Tikamgarh and the larger Bundelkhand region are simple and will hesitate even to enter a private hospital.”

He told ThePrint, “The district hospital is known to all. People have a sense of ownership and walk around freely. Once the private staff takes over, people would find it difficult to find their way around. We had requested the CM and deputy CM against handing over the district hospitals to private players.”

The sentiment was echoed by Harishankar Khatik and Pradeep Jaiswal, BJP MLAs from Jatara and Balaghat, who insisted that for private businesses, earning profit is the primary goal, rather than providing affordable and quality care.

‘Health indicators will worsen’

The grassroot groups, which have come together to oppose the privatisation of government hospitals, wrote to Chief Minister Mohan Yadav last month, underlining that the state of health services in Madhya Pradesh is critical, and that despite several efforts, the government has not been able to implement the Indian Public Health Standards envisaged to improve the quality of healthcare delivery.

According to the letter by groups, such as MP Medical Officers Association and MP Medical Teachers Association, among others, there are currently 2,374 posts of specialists (63.73 percent of sanctioned posts), 1,054 posts (55.97 percent of sanctioned posts) of medical officers and 314 posts of dentists lie vacant across the state. Many CHCs and district hospitals don’t have gynaecologists and essential support staff, making the provision of essential services challenging, the letter added.

Also, according to the National Health Profile, only 43 specialists (surgeons, obstetrics and gynecologists, and physicians and paediatricians), 670 allopathic general duty medical officers, 191 radiographers, 474 pharmacists, 483 laboratory technicians and 2,087 nursing staff are employed at the CHCs in the state.

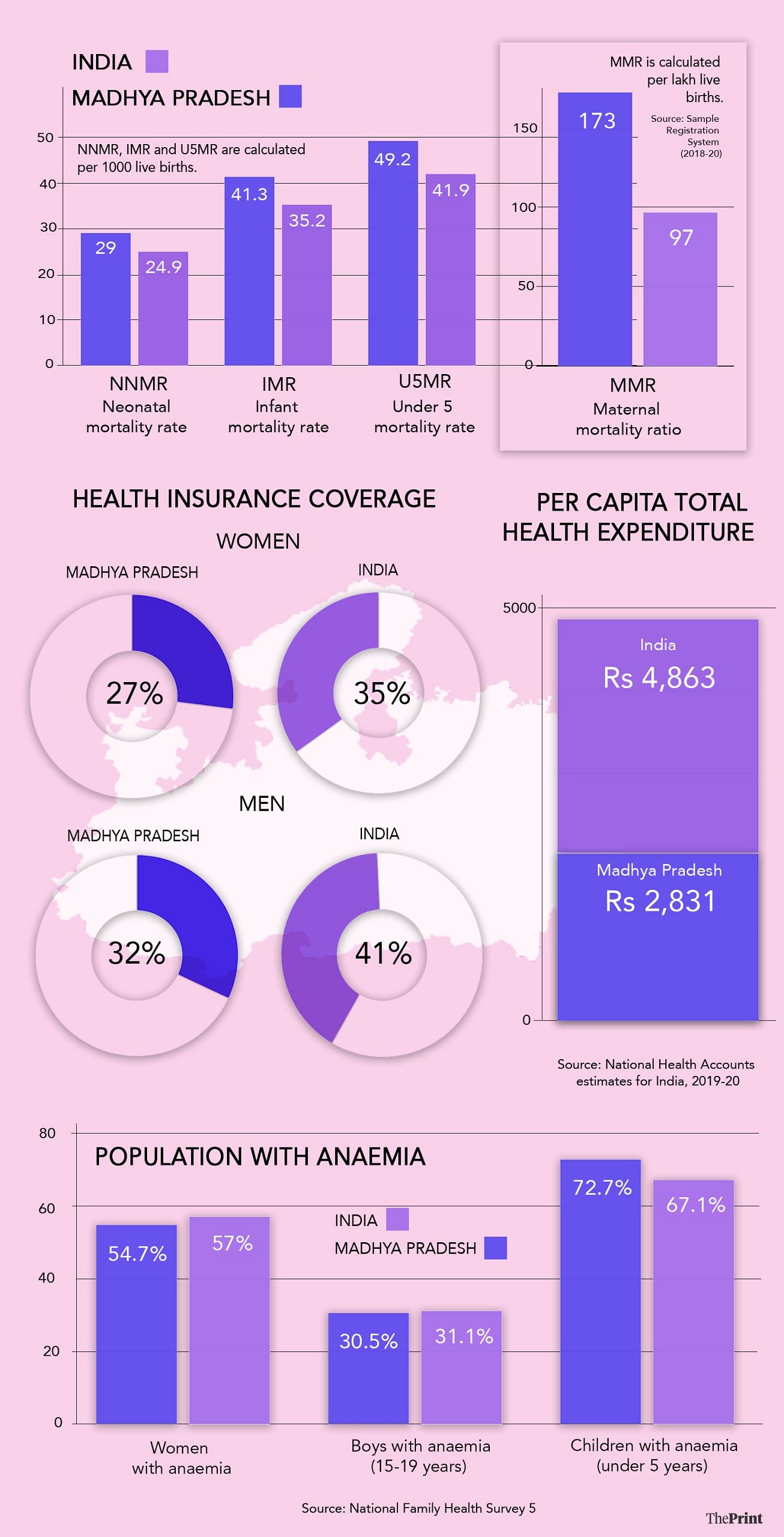

The fact that the healthcare system is grossly underfunded is also evident from the fact that it spends just Rs 2,831 per capita as State Total Health Expenditure (STHE)—a sum of all public and private health expenditures in a state—as against the national average of Rs 4,863.

According to the National Health Account 2017-18, the per capita government health expenditure in the state is estimated at Rs 980, far lesser than the national average of Rs 1,753.

The out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure, as a share of total health expenditure, on the other hand, is estimated at 56.3 percent, which is more than the national average of 48.8 percent, highlighting the burden on the patients.

The healthcare conditions in the state are also reflected in key parameters. For instance, Madhya Pradesh has a maternal mortality rate or MMR (per lakh live births) of 173, compared to the national average of 97, according to the latest available Sample Registration System. The MMR in the state is the third highest in the country among the large states.

The infant mortality rate (IMR) stands at 41.3 (national average of 35.2) and the neonatal mortality rate (NNMR) at 24.9 (national average of 24.9) per 1000 live births, the National Family Health Survey 5 shows.

The protesters insist that these trends will worsen if the government allows private companies to take control of state-run health facilities, as in such arrangements, even if some beds are meant to be free, patients unable to pay may come in lower in the priority scale, or can be turned down on various pretexts.

“We oppose any form of PPP or outsourcing that could lead to the privatisation of health services. Instead, we advocate for the government to convene all stakeholders and discuss improving its public health services, ensuring they remain under government control,” the letter read.

Meanwhile, at the Sidhi hospital, Bhainas was relieved that some organisations are taking up the cause of the poor patients. “Our only sahara (support) needs to be saved. We at least have a place that we can come to when sick. It should not be snatched away from us,” he said, pointing out that he had first rushed his son to the 30-bed CHC in Semaria, but was referred to the district level facility as that centre did not provide emergency care services.

“Where else, if not here, would we go to see a doctor?” an anxious Bhainas remarked.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Why move to junk Indore’s priority bus lanes is drawing flak. ‘Success worldwide, demonised in India’