Offering one kind of beds at market prices would help subsidise regulated ones, suggested the proposal, also endorsed by Union Finance Minister Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in that year’s Union Budget speech.

Madhya Pradesh attempted this model much earlier. In 2015, the Shivraj Singh Chouhan-led BJP government handed over management of Alirajpur district hospital to a Gujarat-based non-profit. The intended aim was to improve the district’s infant and maternal mortality rates.

At 37.2 percent, Alirajpur had the lowest literacy rate among all districts in India (2011 Census). It also had the highest percentage of population who were multidimensionally poor, among all districts in MP.

The state ranked 17 among 19 large states on NITI Aayog’s 2021 Health Index.

The plan to hand over Alirajpur district hospital, however, was shelved within months in view of public outrage, as well as intervention by the Madhya Pradesh High Court acting on a plea challenging the handover without due tendering process. Karnataka, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh, too, had attempted this model prior to NITI Aayog’s recommendation.

From terming it an idea with a twin benefit to arguing it is designed against the poor, public health experts are divided over the efficiency of the PPP model, especially given India’s performance on global health indicators.

India’s score on the Healthcare Access and Quality (HAQ) index, compiled by the Lancet Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Resource Centre, was 39·2 out of 100, as of 2019.

According to National Health Profile 2021, India has 0.6 hospital beds per 1,000 population—as against 2 beds recommended in the National Health Policy 2017 and 3 beds per 1,000 population recommended by the WHO. The private sector accounts for an estimated 58 percent of India’s hospitals, 29 percent of hospital beds and 81 percent of doctors.

The National Health Accounts (NHA) estimate released by the Centre in September showed out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) of the Total Health Expenditure (THE) in India stood at 39.4 percent in the FY 2021-22—down from 64.2 percent in FY 2014-15. Simply put, OOPE is the amount households pay directly at the time of receiving medical care.

Also Read: Packaged, mineral drinking water is now ‘high-risk’ food. What it means

‘Beneficiary should be the public’

NITI Aayog member (health) Dr V.K. Paul said the PPP framework was a result of deliberations involving a multitude of stakeholders and aimed at improving health services in far-flung areas.

“We saw it as a tool to raise access to quality healthcare in remote areas of the country and to give students a chance to study medicine closer to their homes.”

Dr VK Paul, NITI Aayog member (health)

Top executives in India’s private health sector, too, insist PPPs hold immense potential if the project is steered in the right direction through guardrails—shared goals, outcome metrics, and a payment mechanism.

According to Siddhartha Bhattacharya, secretary general of NATHEALTH, a consortium of private healthcare providers in the country, if implemented right, the PPP framework brings expertise from government and private sector to deliver quality, efficiency, innovation and accountability at scale.

“It’s as much about maths and physics as it is about chemistry between the projects and participating partners that sets the foundation for success during the long project duration,” he said.

But some, like former Union health secretary Sujatha K. Rao, are opposed to the idea, arguing that it is “designed against the poor for whom these [state-run healthcare] centres are the only resort”.

“Letting a private player take over the management and operation of a government hospital is shameful and an incredibly bad policy.”

Sujatha K. Rao, former Union health secretary

In September this year, Rao quit the Lancet Commission on healthcare reform stating that the “corporatisation of primary care” in India, along the lines of the US model, is a ‘recipe for disaster in an already unequal society’.

Rao said she favoured a tie-up between private entities and district hospitals, as long as it was limited to training medical students at the facilities at a charge and on conditions fixed by the state. “In a PPP arrangement, the beneficiary should be the public, not the private.”

How PPP model worked out in different states

Several years before Madhya Pradesh attempted the PPP model, neighbouring Gujarat in 2009 handed over GK General Hospital in Bhuj, which replaced the district hospital destroyed in the 2002 earthquake, to Adani Group on a 99-year lease. The hospital is now attached to Gujarat Adani Institute of Medical Sciences (GAIMS), offering both undergraduate and post graduate seats in medicine.

In 2017, the Gujarat government handed over another district level hospital, in Dahod—a largely tribal district—to pharmaceutical giant Zydus, which now also operates a private medical college attached to the facility.

The first instance of the private sector running a state-run hospital was Apollo Group taking over Raichur district hospital in Karnataka in 2002. The state government, however, terminated the agreement in 2013 on charges of poor governance and mismanagement.

Two years later, Apollo, India’s largest hospital chain, entered into an agreement with Andhra Pradesh government to manage operations of Chittoor district hospital. This arrangement continues till date.

ThePrint reached Apollo for comment via email but had not received a response by the time of publication. This report will be updated if and when a response is received.

The most striking instance of such an arrangement failing came to light from Chhattisgarh when the state government handed over the Advanced Cardiac Institute in Raipur to Escorts Heart Institute-Delhi in 2002. In 2017, the state government terminated the contract citing complaints of denial of services to the economically disadvantaged. Escorts Heart Institute-Delhi was later taken over by the Fortis Group.

ThePrint reached Fortis Group for comment via email but had not received a response by the time of publication. This report will be updated if and when a response is received.

In several states, including Madhya Pradesh, unsuccessful attempts have also been made to privatise primary and community health centres.

Public health specialist and independent monitor of the National Health Mission (NHM) Dr K.R. Antony said there are hardly any examples of private players running a government facility in a manner that is beneficial to patients and not driven by profit motive. “Their interest is in profit generation through procedures and diagnoses that bring revenue.”

Private players, on the other hand, argue that linking private medical colleges with district hospitals and community health centers is a forward-thinking move that can address multiple challenges in healthcare, particularly in underserved regions.

“District hospitals and CHCs often struggle with a shortage of medical professionals. Partnerships with private medical colleges can help bridge this gap by providing a steady stream of doctors, nurses, and allied health workers,” said Dr Dharminder Nagar, managing director, Paras Health—a leading chain of hospitals.

These linkages, he added, offer medical students practical exposure to real-world healthcare challenges in rural and semi-urban settings, fostering a more well-rounded education and creating a pipeline of future healthcare providers who are familiar with grassroots healthcare needs.

According to Nagar, who is also a member of the Federation of Indian Chambers and Industries (FICCI) Health Services Committee, these collaborations can also lead to infrastructure upgrades at district hospitals.

He cited the example of Paras Health taking over a hospital under the Heavy Engineering Corporation (HEC), a public sector undertaking, and turning it around.

“Through this PPP, we revitalized a defunct hospital from the 1970s into a state-of-the-art 300-bed facility. This initiative ensured long-term revenue generation for HEC without any capital expenditure on their part, demonstrating how innovative PPPs can optimize public assets while delivering high-quality healthcare services.”

Dr Dharminder Nagar, MD, Paras Health

But for the Uttarakhand government, which decided to hand over 12 CHCs to two local private players in 2012, the experience has been bitter. A senior official in the Uttarakhand health department, while requesting anonymity, said the government cancelled the agreement earlier this year following an internal enquiry which found gross mismanagement.

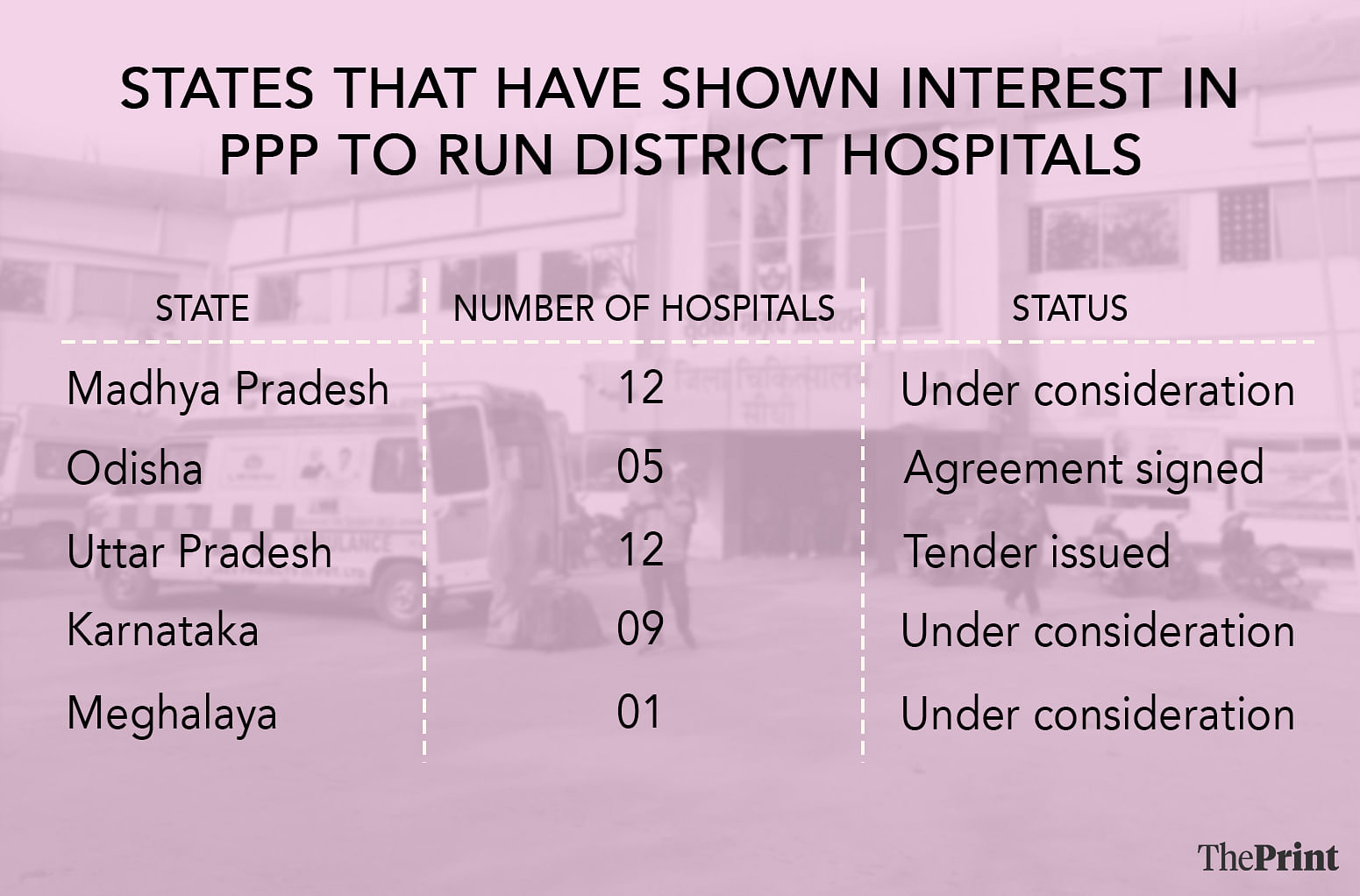

Other states, including Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, and Meghalaya have also moved in the direction of roping in private players to oversee state-run district hospitals or medical colleges.

Also Read: Do herbs have a role in cancer care? India’s top cancer research institute leads projects to find out

‘Polluting Gangotri at the source’

PPP in healthcare is not a novel concept. For decades now, it has been tried at all levels of the healthcare delivery system (primary, secondary and tertiary) through outsourcing of diagnostic and lab services, among others.

More recently, tie-ups with private hospitals for strategic purchasing of healthcare services was at the heart of the Modi government’s flagship 2018 health insurance scheme Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Aarogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY). Under AB-PMJAY, the Centre offers health insurance cover of Rs 5 lakh for secondary- and tertiary-level hospitalisation to nearly 40 crore Indians based on their socio-economic status. In October, it was extended to all Indians aged 70 and above, irrespective of income status.

But those opposed to the PPP model also fear that handing over state-run district hospitals to private players would further ‘crystalise’ the commercialisation of medical education in the country.

Dr Abhay Shukla, national co-convener of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, an umbrella outfit of healthcare professionals and NGOs, told ThePrint, “Not only will this initiative mean handing over unpolished gems to the private sector but it further crystallises commercialisation of medical education.”

“Those paying lakhs and crores per year to secure an MBBS or PG degree can’t be expected to serve the poor. Who is the government trying to fool?”

Dr Abhay Shukla, national co-convener of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan

NHA estimates released by the Centre in September showed that the share of Government Health Expenditure (GHE) in GDP stood at 1.84 percent in 2021-22. Shukla pointed out that in its National Health Policy 2017, the Centre promised to spend at least 2.5 percent of GDP on health by 2025.

States, he said, are ready to hand over district hospitals to private players on the pretext of failure to meet healthcare needs, but the larger issue is that these facilities are underfunded, short-staffed and mismanaged.

Citing the example of the Ganges, Shukla said one cannot expect the river to be clean if its source, Gangotri, is polluted.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: All about nafithromycin, first antibiotic developed in India against deadly, drug-resistant bacteria