![]()

When it comes to camera’s they can come in all shapes and sizes. I want to tell the story of this little, as I call it “Klein Special”, wood box wet plate camera made by my good friend Kevin Klein in Valley City, North Dakota. Coincidently “Klein” means “small” in German. Something that I was unaware of at the time of giving the camera its name.

I befriended Kevin over a decade ago when I decided to take on the wet plate collodion process for myself. As a fellow North Dakotan, he had been practicing here in the state for some years before me. We have both spent much time together in each other’s studio over the years. He recently told me that he was in the process of making a small miniature wood box camera and that it would be completely functional in the field. I was intrigued.

It was poignant that on the 12th anniversary of my first wet plate I would receive this “Klein Special” miniature camera from my wet plate brother in the mail. A small wood box camera that fit in the palm of my hand. It has the ability to capture 1.5” by 1.5” plates. Back in the Victorian era plates of this size were referred to as “Gem” tintypes. Not only did he send the camera, but all the accessories needed to make a wet plate.

The kit includes two plate holders (which he says was the most difficult part of the build), a hand-made achromat two-element lens and lens cap, five Waterhouse stops, a ground glass back, and a silver tank fashioned from a Tic Tac candy box as the insert.

![]()

I immediately took it out of the box and mounted the camera on a small tripod that I had. To my surprise it fit perfectly. To look at the ground glass of this bespoke camera is a fantastic experience in and of itself. At that moment, I knew what I needed to do to celebrate my 12-year anniversary in the process.

![]()

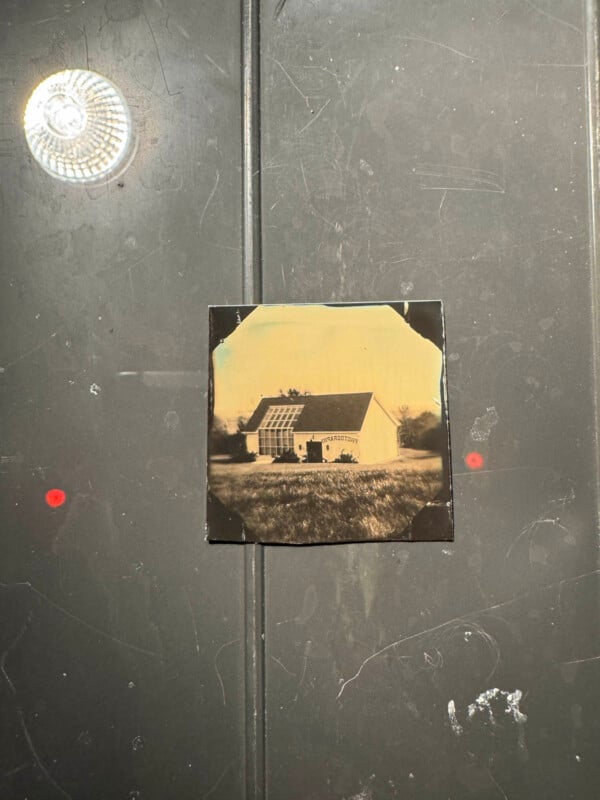

I quickly filled the plastic silver tank up with silver, cut a piece of trophy aluminum into a 1.5” square, and meticulously cleaned it. I then took the camera outside my studio and set it up about 50 yards away and proceeded to use the focusing element of the camera to bring the building into the depth of field. I decided that because it was a bright and sunny day, I would insert the f8 Waterhouse stop into the lens made from two pieces of glass and a brass tube he cut down by hand. This exposure time would be a gut check, but what did I have to lose? I was ready for my first exposure with my new tiny camera.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I rushed back to the darkroom, retrieved the sensitized plate from the tiny silver bath and loaded it into one of the plate holders. As I walked back to the camera I decided to take my chances on a two second exposure. I loaded the plate holder into the camera (it fit like a glove), lifted the dark slide, and removed the lens cap by hand for one-thousand one, one-thousand two seconds and quickly replaced it.

In the wet plate process if the plate dries the image is lost. So, time is of essence, so I ran back down to the darkroom with my little exposed plate. I quickly developed the plate in Ferrous Sulfate / Copper Sulfate developer for about 20 seconds. I then rinsed that plate thoroughly and then placed the plate into the Rapid Fixer bath. I was amazed that immediately an image came to life, and I was thrilled that I hit the exposure on the first attempt.

I felt at that moment that Frederick Scott Archer the man who invented the wet plate collodion process in 1851 in England was somehow looking over me. What would he think about someone 173 years later using his process in modern day to make silver on glass photographs? How the world has changed, but what has not changed is the process that he invented and if it worked then, it works today and at the end of the day, that is all that matters.

I immediately called Kevin and told him that my first attempt was a success. I said “It worked!” and he replied “Of course it did”. I thanked him sincerely for his kindness and told him that the little camera had found a perfect new home, to which he said, “That makes me happy”.

That is how a small little camera and an archaic photographic process from the 1800s can make the world a more beautiful and interesting place.

About the author: Shane Balkowitsch is a wet plate collodion photographer. He has been practicing for over a decade the historic process given to the world by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851. He does not own a digital camera and analog is all that he knows. He has original plates at 71 museums around the globe including the Smithsonian, Library of Congress, The Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford, and the Royal Photographic Society in the United Kingdom. He is constantly promoting the merits of analog photography to anyone who will listen. His life’s work is “Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective” a journey to capture 1,000 Native Americans in the present day in the historic process. You can find more of his work on his website, Instagram, and Facebook.