The space economy is currently worth $8.4 billion in India, according to the Centre’s Department of Space, and the government aims to see it grow to $44 billion by 2033.

Speaking to ThePrint, S. Somanath, chief of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), explained that there is a security and defence angle to India’s space diplomacy.

He said an increased presence of Indian satellites in different orbits around the Earth will help enhance the country’s capacity to track movements of military troops and image large swathes of land.

“Satellites, depending on its range, can observe our country’s borders and our neighbouring land. By increasing our presence in space, we can increase our potential enormously. The power of any country lies in how much they have access to what is happening around them. Knowledge is power in the true sense,” Somanath explained.

The ISRO chief added that a country like India, which is in the race to become a “global superpower” in the coming years, needs at least ten times its current space prowess. The space agency is working towards achieving this target.

“In the next five years, we will be launching at least 50 to 70 satellites, including satellites for geo-intelligence gathering,” Somanath said.

India now has diverse global partnerships with countries such as the United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Lithuania, Spain, Israel, Brazil, Singapore and Switzerland, among others.

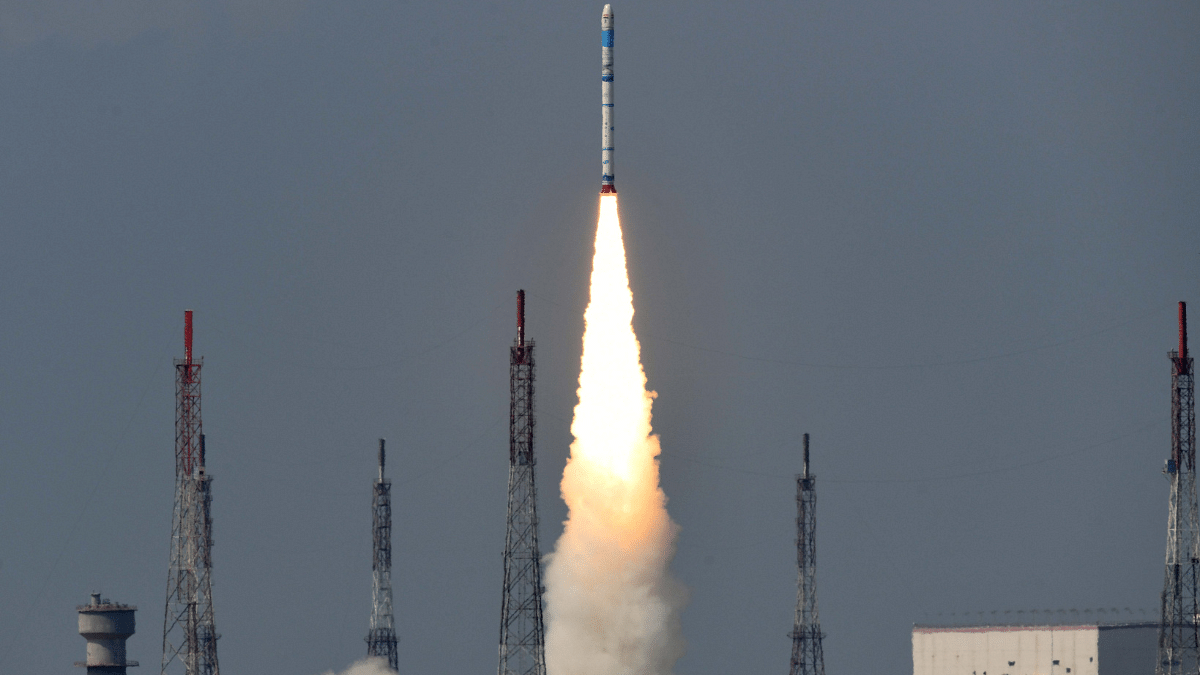

Between 2019 and 2024, a total of 163 satellites built by the aforementioned countries were launched from India.

Besides satellite launches, New Delhi has also been focusing on space cooperation with multiple countries.

Since June this year, the realm of space has emerged in various levels of talks between India and countries including the United States, the Philippines, France, Italy, Brunei Darussalam, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Chile and Nepal, among others.

In recent weeks, space cooperation was part of the talks between India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Sultan of Brunei Haji Hassanal Bolkiah, with both leaders assenting to renew the long-standing agreement between the two South East Asian countries on India’s telemetry, tracking and command station (TTC) in Brunei.

They also looked into exploring the development of satellites and advancement of remote sensing and training.

In consultations with The Philippines last Monday, the idea of space cooperation between the archipelagic country and India was broached.

Last month, India promised assistance to Nepal in the form of a grant for the launch of a satellite.

Also Read: ISRO prepares for responsible space missions, aims to go debris-free by 203

Strategic nature of space

During the Kargil War (1999), India requested the US for access to the Global Position System (GPS) to identify enemy locations, but was denied.

Similarly in 2022, Ukraine requested Starlink—the satellite Internet company owned by Elon Musk’s SpaceX—to extend its coverage to Sevastpool in Crimea. The request was denied, which harmed Kyiv’s military operations in the Crimean peninsula at that time.

Both instances indicate the importance of access to satellite navigation systems for military purposes.

After the incident in 1999, India realised the need for its very own satellite navigation system.

As a result, ISRO decided to strategically design its own answer to GPS— Navigation with Indian Constellation (NavIC), which was launched on 1 July, 2013.

It is a standalone navigation satellite system, which is currently being used on a regional scale but is expected to be developed in the coming years as a “Made-in-India” global satellite navigation system, and touted to be at par with the US’s GPS, Europe’s Galileo and China’s BeiDou.

Last year, the government directed all mobile phone manufacturers to start making all their phone models compatible with NavIC, with effect from January 2023.

Senior officials from the Department of Space told ThePrint that while this is not a strict deadline, they expect major mobile companies, including Samsung, Apple, and Xiaomi, to comply with the directives and accommodate NavIC in their hardware by 2025.

“The space sector is crucial to India’s military capabilities. It is required to know where and how operations will happen. The capabilities in space will indicate how you fight wars on the ground. The growth in India’s space programme will also have gains of strategic value,” Gunjan Singh, an associate professor at O.P. Jindal Global University, told ThePrint.

Anil Prakash, director general of SatCom Industry Association (SIA) of India, explained to ThePrint that the Union Ministry of Defence is increasingly focusing on space-based capabilities, looking at the whole gamut of options—from communications to navigation—to enhance its operational capabilities.

Recent changes in India’s space policies have also witnessed the participation of Indian startups in this sector, with over 200 such companies developing various cutting-edge technologies with applications aimed at aiding the defence sector. Some of these technologies have been supported by initiatives such as the Technology Development Fund.

The next space race is slowly developing, especially with the US aiming to return to the Moon with a human in 2026 through its Artemis programme, and China hoping to achieve the same by 2030. India aims to send its own astronauts to the Moon in 2040.

To achieve its ambitions in outer space, New Delhi has also zeroed in on enhancing its foreign collaborations and international partnerships, such as the US-led Artemis Accords, an initiative launched in 2017.

India’s space diplomacy

Senior officials from the Department of Space explained to ThePrint that India is also improving its bilateral and multilateral relations through developments in the space sector.

Diplomatic initiatives, such as the TTC station in Brunei, are important for India. Before the TTC centre was made operational, launches from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in Sriharikota could not be monitored for about four to five minutes from launch due to geodetic (relating to the shape and area of the Earth) issues. That is why the station in Brunei is key to India’s space programme at the crucial time of launching.

Singh explained that collaboration in the space sector is good for India to promote its soft power and also commercially viable for its companies. “India has a good platform for every country that is aspirational with aiming to have a footprint in space.”

China identified the space sector as an important “digital glue” for its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—the $1 trillion project by Beijing which envisages new land and maritime trade routes connecting the country with Africa and the South Pacific, as reported by The Wall Street Journal.

China’s space programme and its own global navigational system, BeiDou, has also gained acceptance among the countries which are part of Beijing’s BRI.

Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka are some of the countries which agreed to cooperate on the expansion of BeiDou, indicating how space programmes can also have diplomatic benefits.

Prakash explained that since the launch of Chandrayaan-3, there has been growing interest in India’s space programme, especially due to its cost effectiveness, competence and credibility. For instance, the UK and Africa have shown interest.

“The success of the Chandrayaan-3 mission has showcased India’s competence and credibility with regards to its space programme. This has made other countries take note and become interested in cooperating with ISRO and the Indian private sector,” Prakash said, adding that there are close to 600 companies in India’s space sector today.

About 350 of them are small and medium enterprises, while about 200 are startups. About 50 companies have grown due to their cooperation with ISRO in the last three decades.

“While India’s private sector is growing, there are challenges including the lack of consortium building across the sector, especially as these companies are specialised in specific areas or products—all of which may be required in one mission,” Prakash explained.

The government expects the private sector to play a large role in achieving these targets, which would be invaluable for India’s space diplomatic arm.

India wants a seat at the high table

India’s space ambitions also include having a seat at the global rule-making table, one of the reasons behind it joining the Artemis Accords.

The Accords indicate a level of close partnership between India and the US in the realm of space. It could potentially give India access to higher technologies in the space sector, which would be beneficial for the country.

The NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) mission is an example of the higher technologies in space that can be achieved through this collaborative approach. The joint project would see the launch of the most advanced radar system on a NASA space mission.

“We are pursuing bilateral and multilateral relations with space agencies and space-related bodies to build and strengthen existing ties between countries, taking up new scientific and technological challenges, refining space policies and defining international frameworks for utilising outer space for peaceful purposes,” ISRO says on its website.

(Edited by Radifah Kabir)

Also Read: ‘We are scientists, not beggars’. Indian Science Congress is in a war against govt