However, the Congress government in Telangana has now set out to change a system in which caste determines the quality of school infrastructure and access to opportunities. The ambitious aim is to build new integrated schools in all of the state’s 119 constituencies, each with a budget of Rs 125 crore.

Revanth Reddy, the chief minister, argues that these Integrated Residential School Complexes (IRSCs) will “foster inclusivity”. The mission statement is to “transform the residential educational ecosystem”, and impart “communal harmony and unhindered opportunities for talented children from the poorest of poor strata” of each community, according to the state’s education department.

“It will promote a sense of brotherhood and unity among students, instead of filling poison in their minds by making them study separately,” said the chief minister, who also holds the education portfolio, while inaugurating the project in October. “Should SCs, STs and OBCs lead their lives herding sheep and goats?” he asked.

Over the past 50 years, Telangana—formerly part of undivided Andhra Pradesh—has operated social welfare residential schools in order to ensure that the brightest children from each marginalised community have the opportunity to attend a residential school where their needs are met. The schools have been so successful that they are the subject of case studies by Harvard Business School and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

But rampant and sudden expansion of the residential school system has led to inadequate infrastructure, poor food quality and a situation where children from marginalised groups are more likely to seek out schools catering to their own community.

“I think integration will be a very good thing for all schools,” said Naveen, who studies at a general residential school on the outskirts of Hyderabad. “The only reason I wish I had gone to a school for STs was because they provide everything for students, even uniforms. All students of all castes should have the same facilities, so integration is a good idea.”

Today, there are around 7.5 lakh students studying at 1,023 government-run residential schools, operating under four different societies (and in the case of the general schools, the education department)—21.5 percent of all children aged between 10 and 16 in Telangana study in such schools.

While some ask why the Congress government wants to fix something that’s not broken, others say the plan is simply to elevate the entire system. The aim is to have world-class institutions offering the best education to meritorious students from rural Telangana across all caste groups.

“Intermixing will help students perform better and learn from each other. It also helps fulfil our constitutional obligations to reduce social inequalities, because it will help students break out of their community mindset,” said B. Venkatesham, principal secretary of Telangana’s education department, who is himself a product of the state’s first ever residential school in Sarvail.

The project will be piloted in CM Revanth Reddy’s constituency, Kodangal, and Deputy CM Mallu Bhatti Vikramarka’s constituency, Madhira, where current students of SC, ST, BC, minority and general schools—especially those that have subpar infrastructure or are functioning in private rented buildings—will be brought onto one campus.

Students from every community will study together, dine together, and go home to different hostels, which will be based on community. The groundbreaking was done in October 2024 and if construction goes to plan, the new school will be functional by the next academic year.

“If politicians really want to abolish the caste system, integration of schools is the best way,” said Ranjita S., an English teacher who teaches at an SC school in Narsingi.

Also Read: Madrasas in UP aren’t asking for govt recognition—they’re trying to lose it. Here’s why

The beginning of ‘segregation’

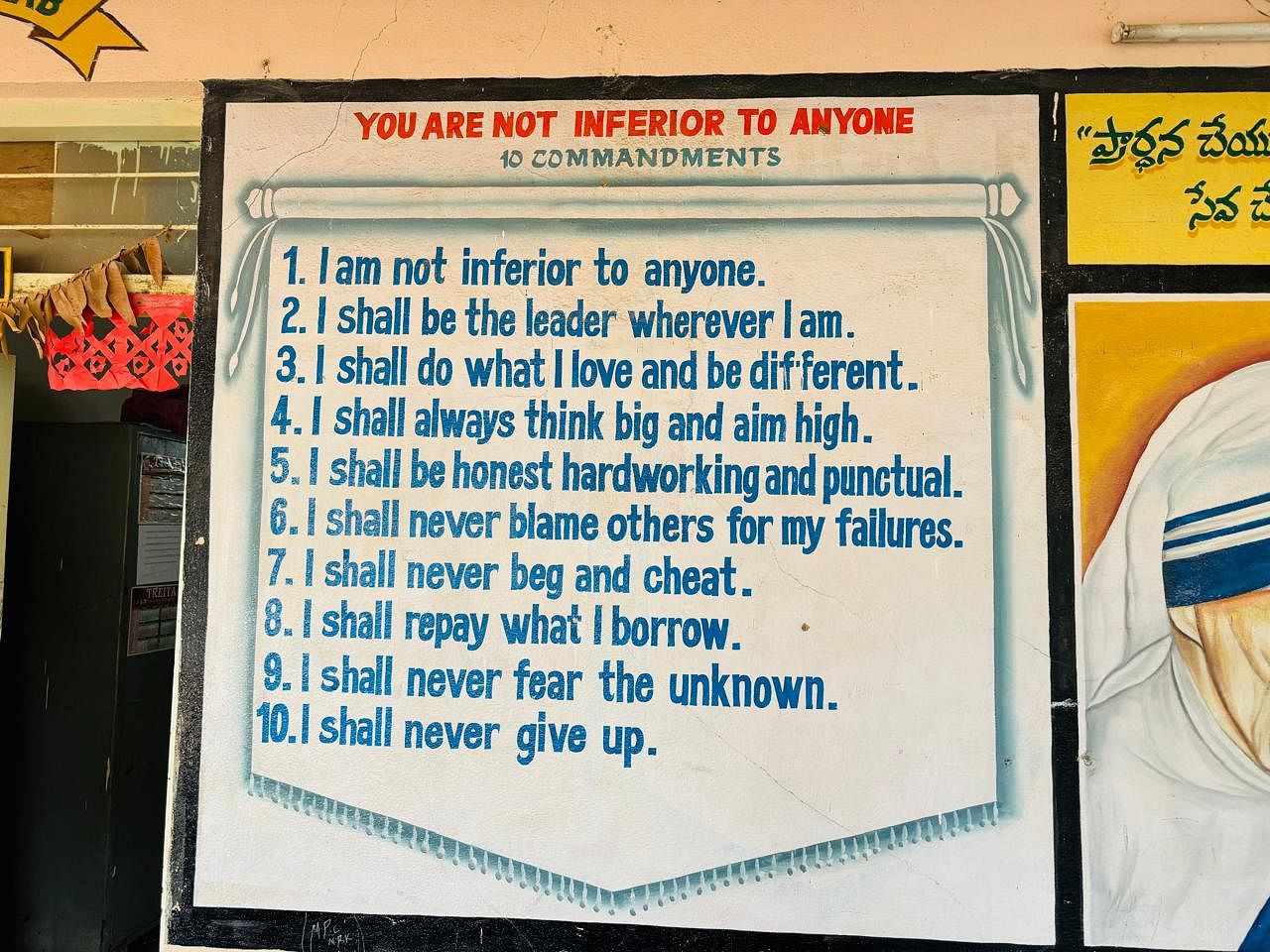

The first commandment of Telangana’s premier school of excellence—a boys’ school in Sarvail—is, “You are not inferior to anyone.” This simple message would become the basis of the state’s entire education setup.

The two moments that definitively changed public education in Telangana were the setting up of this tiny residential school in Sarvail in 1971, and the year 2014, when a 13-year-old tribal girl from an SC school became the youngest girl ever to scale Mount Everest. Both changed the landscape of public education in the state.

Telangana traces its social welfare schools back to the early 1970s, in the erstwhile united Andhra Pradesh. Congress stalwart and then chief minister P.V. Narasimha Rao had set up the school in Sarvail in 1971, reportedly inspired by a trip abroad, where he visited government-run residential schools.

Students from rural Andhra were encouraged to take an entrance exam to secure a coveted seat at Sarvail, where they would go on to spend seven years—from class 5 to class 12—in a fully residential facility, monitored by teachers, who were available to them 24/7 in a gurukul system. The number of students was limited and seats were reserved for children from every community.

The school worked: today, its alumni range from civil servants like Venkatesham and former Telangana DGP Mahender Reddy to accomplished doctors, engineers and academics, who have also gone on to work abroad.

This type of educational setup, the brainchild of Padma Bhushan-winning civil servant and activist S.R. Sankaran, was so successful that it eventually became the blueprint for Navodaya schools, implemented by Rao as human resources development minister in the 1980s under the Rajiv Gandhi-led government. It also inspired the then chief minister of Andhra Pradesh, N.T. Rama Rao, to set up a similar school exclusively for children from the Scheduled Castes.

Thus began the process of segregation in government education.

The SC social welfare schools were set up in 1983 under the Telangana Social Welfare Residential Educational Institutions Society (TGSWREIS), with its ST counterpart, Telangana Tribal Welfare Residential Educational Institutions Society (TGTWREIS), following in 1999.

Schools for children from OBC communities were set up in the Mahatma Jyothiba Phule Telangana Backward Classes Residential Educational Institutions Society (MJPTBCWREIS) in 2012 and minority schools were registered under Telangana Minorities Residential Educational Institutions Society (TGMREIS) in 2016.

Each of these societies reserved a majority of its class strength for students from one particular community, keeping a few seats for students from other communities.

“Sarvail is the school that led to residential schools,” said Shekhar Reddy, who teaches mathematics there. “The other four societies were born to serve students from their communities. This school was founded to give rural children from all backgrounds the right opportunity. Merit should be the most important consideration, not caste. So here we ignore caste and teach our students to perform well academically, rather than only aim for a certain rank or mark depending on their caste background.”

The number of schools dramatically soared after the year 2014, when 13-year-old Malavath Poorna became the youngest girl ever to scale Mount Everest. An ST student at an SC school, she became a symbol for the success of such schools. Soon after, then chief minister K. Chandrashekar Rao immediately sanctioned hundreds of new such schools.

Graduates from such schools were going on to crack MBBS, NEET and UPSC examinations. They were getting admission to IITs and NITs as well as private institutions like Ashoka University and Azim Premji University.

The government also set up niche sports facilities, like shooting, archery, boxing and fencing, so that students could excel at national-level athletics. Students like Poorna are mentored and trained at such schools. In fact, an SC school in Hyderabad has a government-funded gym that’s so well-equipped that local athletes use it for training.

The Bharat Rashtra Samithi-led Opposition has questioned why, then, the Congress is undertaking such a project.

“These schools are already integrated. They’re not monocultural or homogenous,” said retired Indian Police Service officer Dr R.S. Praveen Kumar, former secretary of the Telangana Social Welfare Residential Educational Institutions Society, who joined the BRS in 2024. “I handled this system for nine years. Every caste is there. It’s an ingenious way to educate students. The Congress government is selling old wine in a new bottle.”

Determined students, sceptical educators

Students across the schools run by the four societies are open to possible integration because they have all heard the schools will have smart boards, computers and state-of-the-art facilities.

Madhumita, a 15-year-old OBC student who currently attends an SC school and has also studied at an ST school, is excited about meeting those from other backgrounds. She has already learned so much about other cultures, festivals and foods by virtue of studying in both SC and ST schools.

“I’ve learned how to accommodate and acclimatise,” she said. “When we’re exposed to others, we learn more. I know about caste discrimination. Every coin has two sides, so we have to see the opposite side, too. Society separates us.”

Udaisri, her classmate from the Madiga community, interrupted her. “Actually in my village, OC (other castes) people dominate us. After coming here, I met other castes and I know that everyone is equal. But in our village, it’s not like that. I want to destroy that in our village.”

The other friends nodded. The girls—a group of OBC and Dalit students—agreed that if they ever run into caste conflict amongst students in a future IRSC, they will have a civil conversation and explain where they are coming from.

Across the city, at a minority school, students say that both Hindu and Muslim students coexist in peace. Encountering communal tensions is something they have thought about “outside” but has never been a problem within the school.

“We’re living in an integrated way already. We don’t talk about caste and religion, our friends are our family,” said 17-year-old Nazneen, who studies at a minority school on the outskirts of Hyderabad. “I encourage everyone to come to my school. We have almost 30 computers here, more compared to other schools. Plus, we have the best food!”

Teachers are slightly more worried about the potential integration. Food and dietary habits seem to be the biggest cause of concern. Those at a tribal school say tribal students require more nutrition, while minority schools offer a slightly greater variety of non-vegetarian meals. The school food plans are standardised under each society, with each school following roughly the same menu with the same dietary allocations. But across the board, teachers and wardens complain that the meat allocation—calculated by grammes per student—is not enough for growing children.

The principal of a BC school is particularly sceptical. He/she believes the integration of “minority students” may have a fallout with parents who might not be comfortable with their children studying and living with children from other religions.

Siddartha Nemali, 23, who studied at an SC school from 2011 to 2020 before graduating from Ashoka University, thinks that possible bias could come from teachers who move to IRSCs from other schools.

“I’m very grateful to my school because I never experienced caste discrimination and was insulated from any casteist behaviour. While I have never personally experienced this, I know that there are chances of conflict between students of different backgrounds, but the bigger concern is that teachers could take out their bias on students,” said Nemali. “Caste background cannot be hidden: maybe through names, or when parents visit hostels, it’s possible to identify a student’s caste. I hope teachers are not biased, and the government will proactively identify such cases and work to prevent it from happening.”

Also Read: Did humanities focus slow India’s progress? New study says vocational education helped China grow

Problems with infrastructure

At an ST school in Ibrahimpatnam, the students’ classrooms double as their dormitories. Soap dishes and toothbrushes line windowsills, each classroom sandwiched by a blackboard to the front and towels drying on clotheslines at the back. The games room doubles as a sick room, with three feverish students lying next to a pile of balls. Running water is an issue, and students often defecate openly around the rock face behind the school.

“I don’t know about integration,” said 17-year-old Vinay Kumar thoughtfully. An ST student, who aspires to go into government service, he chose this particular school because he wanted to study with others in his community.

“I’m not saying it’s right or wrong. I’m more comfortable here than in a corporate school, where I have experienced casteism and discrimination. There’s a 50/50 chance such schools will work. We fear we’ll be discriminated against by them. I don’t want to feel inferior. I utilised my caste to get admission to this school, and I’m happy because at least I got a seat,” he said.

The students are bright and engaged, some speaking better English than their teachers. Their demands are simple—more olympiads for them to compete in, better food and improved water quality.

Vinay broke off to chat with another classmate in Lambadi. “We need more training and exposure. Some of us need to improve our communication skills. So maybe exploring more with students from other communities would help with this,” he said.

The school isn’t an anomaly. Most schools located away from urban centres have crumbling infrastructure, packing students into whatever space is available. This particular school is government property, but located in a largely tribal area so that parents feel comfortable sending their children to a school close to them.

Other schools are often crammed into private, rented buildings—692 of the 1,023 schools are in rented buildings, and 450 have insufficient space for accommodation. This is the pool of schools Revanth Reddy is targeting, according to the education department. Some civil servants remember KCR’s overnight mandate, ordering the setting up of hundreds of such schools in 2014. Many district magistrates were forced to identify buildings that could house schools within a month, leading to uneven infrastructure across all.

In Keesaragutta, three BC girls’ schools are stuffed into one building, with one principal. Children practise fencing—the school has sent girls to compete in national competitions—in front of a small park covered with drying clothes, and rats dart in and out of the pantry’s storeroom as cooks carry armfuls of vegetables to cook in dingy kitchens.

“Children are not chickens!” said the BRS’s Praveen Kumar, referring to the fact that IRSC will combine four schools with 640 students each into one school of 2,560 students. The planners of the original schools, he said, intelligently restricted the number of students to ensure enough attention was given to each child. “Having this many children in one place with the same number of teachers is not going to work; 640 students is already an unmanageable number.”

Alumni of SC, ST and minority schools say that segregated social welfare schools insulated them from potential caste discrimination, but students from general and BC schools feel a lingering resentment. They believe that SC, ST and minority schools have better funding from the government to cater to fewer students, even though residential schools have the same sanctioned strength of 640 students.

“My school focuses on education, while those other schools focus on welfare,” said Naveen, the ST student who studies at a general residential school. What he meant was that social welfare schools provide everything for students—from socks, uniforms and blankets to textbooks and notebooks—while general schools, funded by the education department and not social welfare societies, struggle with providing such facilities.

The school he studies in is due for major renovation. Teaching staff stay in dilapidated buildings, while students have to wade through waterlogged corridors to make it to stinking bathrooms. In one staff quarter—abandoned because of how unliveable it is—lie the bones of a dead dog.

Educationists and child psychologists alike say that the plan for IRSCs is good on paper—not only will it give rural children from all caste backgrounds a chance to interact in a safe space, it will also expose them to world-class infrastructure, which could boost their learning outcomes and morale. According to them, studying and dining together in such classrooms and dining halls will help integration, while also allowing students to go back to hostels where they will be surrounded by other students, who come from the same castes and cultural backgrounds.

“This is a good idea, especially because it will acknowledge the digital divide. In this day and age, merit often gets lost in the digital divide, especially amongst the marginalised,” said Sujatha Surepally, educationist and advisory member of the newly appointed Telangana State Education Commission.

“Telangana has a layered education ecosystem, with such gurukul schools functioning alongside zilla parishad schools and other models. We have been working towards a common education system for ages. Another student should not be deprived because of these layers. Every student, irrespective of caste, should have equal opportunity and accessibility in terms of education.”

The government roadmap

The Congress government began work on its plan in October 2024, breaking ground in the constituencies of Kodangal and Madhira, and identifying forty other locations.

By 2027, the government aims to have 119 such integrated schools, budgeted at Rs 63,500 crore. Each IRSC will be spread out over at least 20 acres, and will house everything from swimming pools and state-of-the-art computer and science labs to hostel dormitories and upgraded dining complexes. Each school will be equipped with e-classrooms, digital libraries and smart boards.

Over the next four years, the government plans to enrol an additional 4 lakh students and scale up the IRSCs. The aim is to also cater to children of migrant families, which form about 37 percent of Telangana’s population.

“This is an opportunity for all communities to stand shoulder-to-shoulder, in a better environment,” said Varsini Alugu, secretary of Social Welfare Residential Schools. “The only reason for the chief minister to do this is to maximise resources and create a real-life simulation for children in their adolescence.”

The education department is keen to clarify that the number of seats will not be reduced, nor will funding to the social welfare societies be cut. All resources will simply be pooled into one campus and every IRSC will continue to keep 25 percent reservation for children belonging to each community. The plan is to identify schools with particularly bad infrastructure and relocate those students first before scaling up.

Saying that the project looks “romantic, progressive and germane” on paper, Praveen pointed out that no research study has been conducted to evaluate whether or not the current model is failing at addressing casteism.

“What Revanth Reddy should do instead is construct smaller schools at local levels like mandal headquarters and make sure the syllabus is revamped,” he said. “That will truly attack casteism in society, and ensure that all children, even those who don’t get into such residential schools, grow with a different outlook.”

Alumni of such social welfare schools agree—casteism should be attacked at the root and cannot be rooted out through just integrating schools.

“My opinion is that it is easy to merge them, but issues are inevitable,” said Nemali. “We see so many cases of caste discrimination not being addressed in society and no action is taken. In a hostel system, students are more vulnerable. The government should ensure that there are redressal mechanisms for such cases. It’s a good thing that schools won’t be segregated. We should hope that students and teachers don’t end up treating each other badly.”

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: What is Cabinet-approved PM-Vidyalaxmi & how it will benefit 22 lakh meritorious students each yr