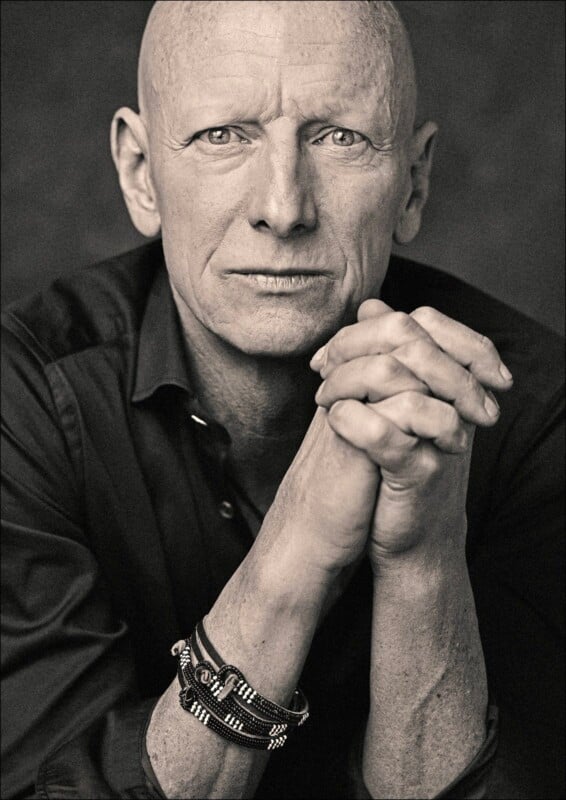

English photographer Jimmy Nelson, best known for his portraits of tribal and indigenous peoples, was recently announced as the winner of the $100,000 Special Appreciation Award at HIPA, the world’s most lucrative photography competition backed by the crown prince of Dubai. PetaPixel sat down with Nelson to talk about the prize, his life, and his inspiring career.

Shaped by Childhood Trauma

James ‘Jimmy’ Philip Nelson was born in Sevenoaks, Kent, England, in 1967, and he spent his early years moving to different areas around the world with his father, who was a geologist.

“I spent the first seven years of my life traveling,” Nelson tells PetaPixel. “Many of the countries I now work in, are ones I lived in as a child. So I was from a very early age, deeply invested in the world.”

When he was seven, Nelson was sent back to the United Kingdom to attend a traditional boarding school, and that’s when his life took a dark turn.

“There were one thousand little boys and four hundred Catholic Jesuit priests,” Nelson recalls. “Things went wrong — things that Catholic Jesuit priests did to little children. And all my trust in myself and in humanity died.

“I went into lockdown as a teenager, and then at the age of 16, it was cataclysmic events. I was very ill with malaria. I was given the wrong antibiotics, and I was locked in a room for two weeks in the school. My hair fell out. And one day I came out of the room and everybody went, ‘Oh wow, Jimmy, some serious s**t’s gone down with you. You are very ugly.’ And I thought, ‘Wow, that’s funny. I’ve kept this secret to myself since I was a little boy. But now my secret is out because the ugliness I feel inside is now on the outside.’”

Embarking on a Trek Inspired by Tintin

In 1985, at the age of 17, Nelson fled his boarding school and journeyed out into the world.

“As a result of [those traumatic experiences], I ran away and I ran into the world inspired by Tintin, who was my avatar as a child,” the photographer says. “Obviously I was born in the late sixties and Tintin went to Tibet, and in Tibet, lots of little children around with no hair.

“I was 17. I dressed up as a monk, and I walked into Tibet, and that’s where my journey started.”

Nelson brought along a Soviet Zenit B 35mm SLR camera and some rolls of Kodak Gold film. After shooting some portraits of people in Tibet and having the pictures published, Nelson jumped headlong into his lifelong exploration of photography and art.

“The journey is about, how can I see myself if I hate my body and my appearance? How can I relove it? Because if you’re talking about sustainability, if we don’t love ourselves as individuals, and if I don’t like you, how the f**k are we going to look after this planet? So that was the beginning of the journey.

“On that journey of three years [from 1984 to 1987], I walked into a country that was in severe lockdown. Tibet had been closed for 30 years after the Chinese had entered in the early 1950s. The Chinese had decided to take it and destroy it, but amongst all that pain and fear, they were very kind to me. And they held me and they said, ‘Jimmy, we see you.’”

The Sustainability of Humanity

In the decades since, Nelson has become an internationally recognized photographer through his beautiful portraits of indigenous peoples across the globe. He views the sustainability of humanity as being integral to the sustainability of our planet, and his work is done through that lens.

“The journey is: first of all, I have to be sustainable,” Nelson says. “I have to wake up in the morning and look in the mirror and go, ‘Hey, you are the business.’ If you don’t, don’t do that. Life is going to be very short at the age of 57. I want to live another 40 years, without cryogenically, storing myself. So that’s the first lesson of sustainability. I love what I do. It’s highly complex and highly difficult. So I’ve got to be 100% sustainable — that’s love.

“Then I love other people, but I have to find a way to communicate. And then I want to persuade humanity with the work that I do, that human beings have a future. It’s a little bit melodramatic.

“Once that’s all aligned, then we can worry about the planet.

“But if we don’t like ourselves and we don’t like each other, we listen to megalomaniacs who tell us to go and s**t on each other, then there’s no sustainability whatsoever. It doesn’t matter how many solar panels we hang from our roofs. So in that context, it’s more of a spiritual human sustainability. We’ll destroy each other before we destroy the world, which is what we are doing. We have to get back to that place of love.”

On the technical side, Nelson shoots with a handmade large format camera and Kodachrome ISO 50 film.

Winning the $100,000 HIPA Prize

Nelson says that when he was first contacted by HIPA and informed about winning the $100,000 prize, he wondered whether it was a scam. Luckily for Nelson, a friend of his won a HIPA prize just one year prior, and that photographer put Nelson at ease.

“A photographer called Fran Laning, who lives in California actually, won grand prize this last year,” Nelson recalls. “I contacted him and said, ‘Is this a genuine organization?’ He said, ‘Yes, take them seriously.’ So then that’s when I realized it was something very special.”

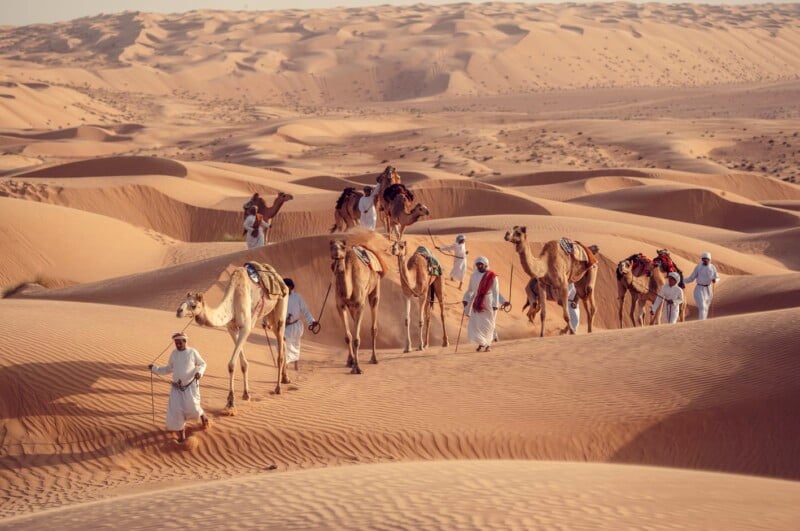

“Coincidentally, I’m working in Saudi Arabia at the moment,” the photographer continues. “My future project will be in the Greater Middle East, so I traveled in from a place called Tabuk yesterday, and I go back there today. I thought it was nice serendipity that my work is in the Greater Middle East at the moment, although I haven’t publicized or promoted it yet.”

Nelson was handed his trophy in an award ceremony in Dubai on November 12th, which just so happened to be his birthday. It was the first monetary prize he had ever been awarded for his photography.

The HIPA award announcement reads: “James ‘Jimmy’ Philip Nelson, a Dutch photographer known for his work with indigenous communities, received the Photography Appreciation Award for his significant contributions to photography and projects that foster greater understanding between different cultures.”

Nelson says that the prize money will help him pay off debts that have built up over his career.

“I’ve lived ever since I started as a photographer in debt because whatever comes in goes out,” Nelson says. “It just fills a big hole. But it’s great, it’s wonderful. It means I can carry on. Everybody who’s helped me over the years, I owe money to, so I’ll pay them, and then I’ll wait until the next hole is created and then somebody else will help me fill that up.”

Traveling the world with a large format film camera doesn’t come cheap.

“A box of 10×8 analog film is $200. Process it, scan it, develop it, print it. It’s insurmountable. This [$100,000] prize is amazing, but it doesn’t mean I go off and buy a fancy watch. No, just goes back into the big hole of carrying on with this journey. But it’s wonderful because the hole’s big.”

Nelson also started the Jimmy Nelson Foundation to give back to the indigenous peoples who embrace him and pose for his portraits.

“We invest in cultural projects,” the photographer says. “We try to encourage them. The culture and what you have is important to hold onto.”

Nelson’s Advice for New Photographers

When asked about the single piece of advice he would give new photographers, Nelson was quick with his answer.

“Park the concept of photography and dare to become an artist.”

While the technical aspects of any art form are important, Nelson believes that one should first focus on creating a voice before turning one’s attention to the outlet for that voice.

“It’s the artistry of self,” he says. “We’re all artists. We’re all individuals. Dare to find that authenticity and that voice, and then the medium you need to communicate, it will come. And maybe that’s the camera. Don’t buy the camera looking for the photo, because it doesn’t require any effort anymore.

“But discovering the artist is the biggest, most complicated journey that there is.”