The widespread use of chemical weapons has been condemned as war crimes, although Assad’s government denies responsibility.

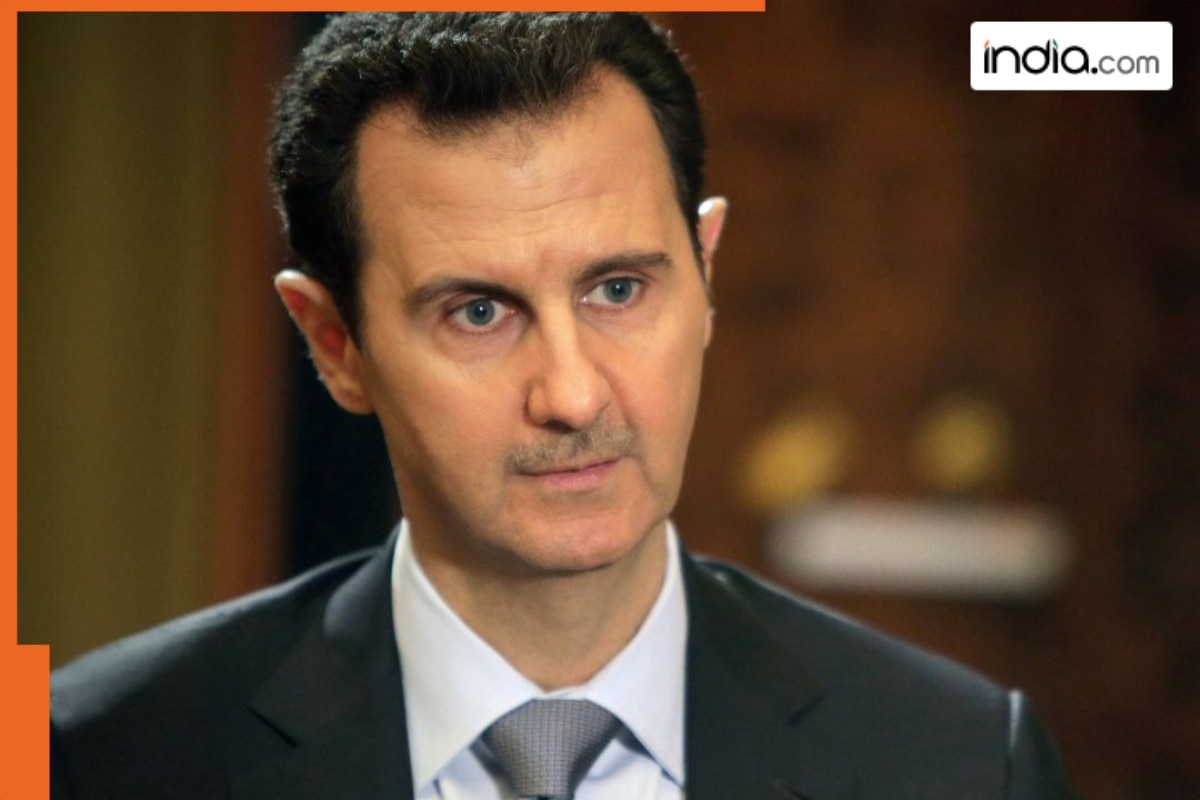

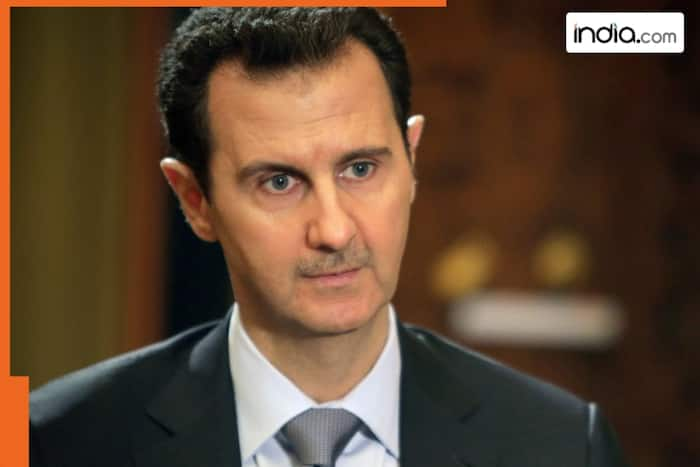

When Bashar al-Assad assumed the presidency of Syria in 2000, his authority was unquestioned. He succeeded his father, Hafez al-Assad, who had ruled since 1970. Hafez had consolidated the Baath Party’s power, aligning it with the Soviet Union and creating a robust political and military leadership dominated by members of Syria’s Alawite minority, to which the Assad family belongs.

Bashar, a trained ophthalmologist educated in London, was not the original heir to power. His older brother, Bassel, had been groomed for leadership until his death in a car accident in 1994. Following Hafez’s death, Syria’s parliament swiftly amended the constitution, reducing the minimum age for the presidency to 34, enabling Bashar to take office without opposition.

Initially, Bashar al-Assad was welcomed by Europe and the United States as a young, modernizing leader. This optimistic image was bolstered by his wife, Asma al-Assad, a former London-based investment banker. However, hopes for reform were short-lived. Assad strengthened ties with militant groups like Hamas and Hezbollah, and his violent crackdown on pro-democracy protests in 2011 marked the beginning of his international isolation.

In May 2011, U.S. President Barack Obama condemned Assad’s regime for its violent suppression of dissent, urging him to either embrace democratic reforms or step down. Despite this, Assad has remained in power, securing re-election every seven years by overwhelming margins. Western nations, however, have dismissed these elections as fraudulent, with the most recent held in 2021.

The Syrian civil war, which erupted after the 2011 protests, became a defining feature of Assad’s presidency. On August 21, 2013, forces loyal to Assad launched rockets filled with sarin gas at opposition-held areas near Damascus in the Ghouta chemical attack. The assault, which caused between 281 and 1,729 deaths, became the deadliest use of chemical weapons since the Iran-Iraq War. Nerve gas, a lethal agent that disrupts the nervous system, caused victims to suffer from paralysis, respiratory failure, and death.

The Ghouta attack was part of a broader pattern of chemical weapons use attributed to Assad’s forces. Organizations like the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPI) and Human Rights Watch have recorded over 300 such incidents between 2012 and 2019. Notable attacks include:

● Khan Sheikhoun (2017): A sarin gas attack that killed nearly 100 people and injured hundreds.

● Douma (2018): A chlorine gas attack that resulted in dozens of deaths.

The widespread use of chemical weapons has been condemned as war crimes, although Assad’s government denies responsibility. In 2013, UN inspectors confirmed the use of sarin gas in Syria, describing the findings as “clear and undeniable.” The attack spurred international efforts to dismantle Syria’s chemical weapons stockpile and increased U.S. support for opposition forces.

Despite mounting evidence and international outrage, Assad’s grip on power remains firm. In 2015, he rejected participation in a U.S.-led coalition against ISIS, a terrorist group that had seized large portions of Syria during the conflict. Meanwhile, the war has left a devastating legacy. According to the United Nations, over 7 million Syrians have been displaced within the country, while more than 6 million have sought refuge abroad.

Assad’s rule, marked by unfulfilled promises of reform and the widespread use of violence, has solidified his reputation as one of the most notorious leaders of the 21st century. His presidency represents not only the persistence of authoritarianism but also the profound human cost of war.