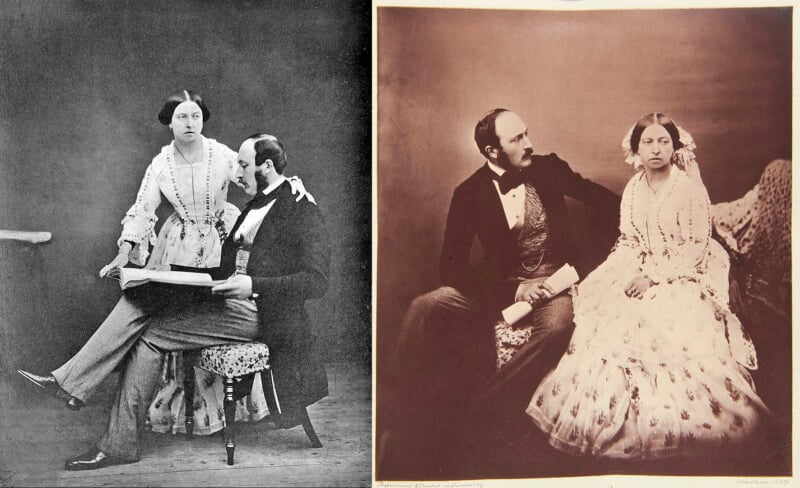

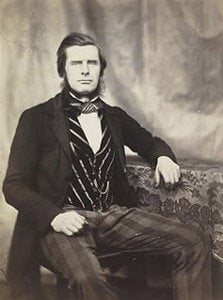

Roger Fenton is best known for Valley of the Shadow of Death, one of the oldest-known photos depicting war. His relatively short 10-year photography career sparked accusations that he was a government propagandist while simultaneously being praised as one of the medium’s pioneers.

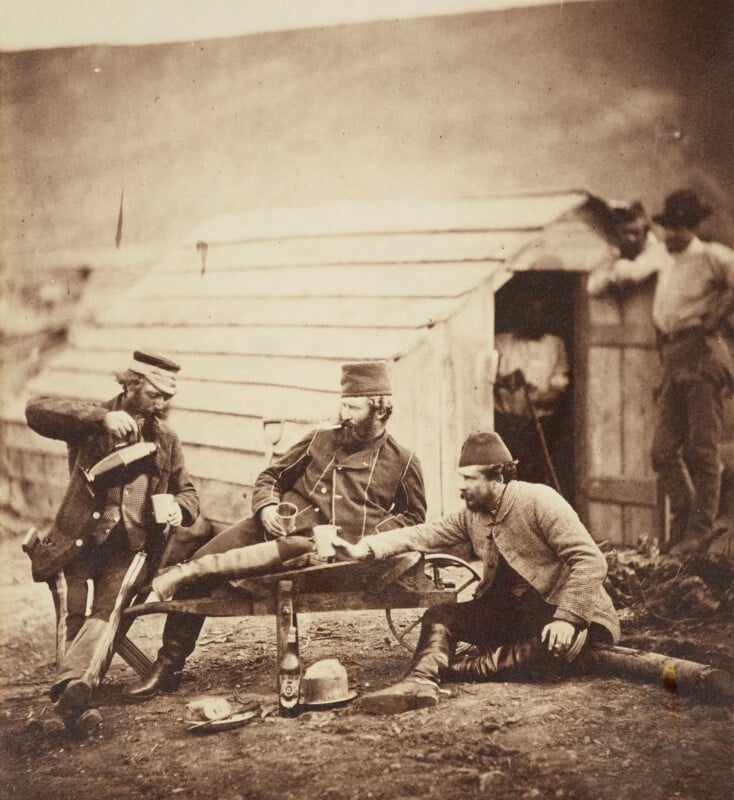

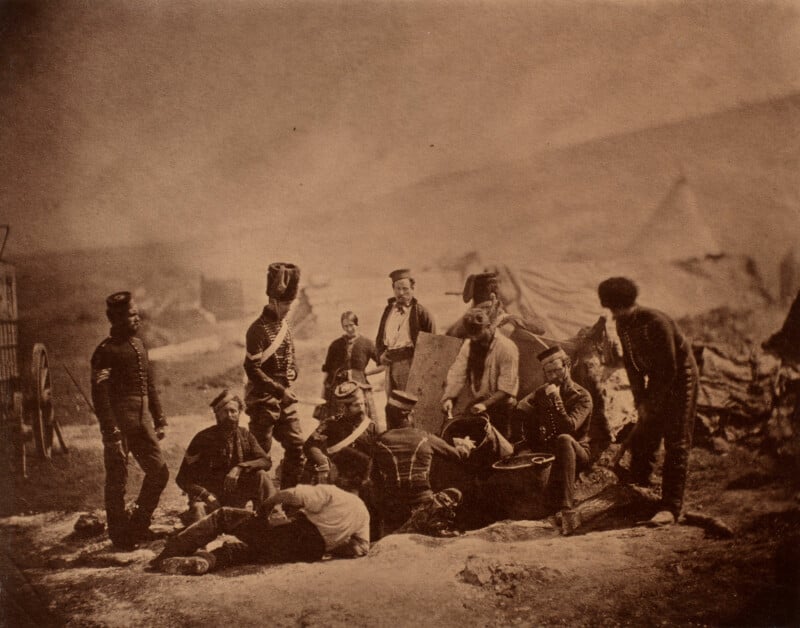

Fenton, a member of the British landed gentry, took portraits of Queen Victoria and her family as well as images of odalisques; Muslim concubines. But it is the Crimean War (1853 to 1856), fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, and the United Kingdom, that he is best known for.

Fenton was not the only or first photographer in Crimea. The Library of Congress notes that prior to Fenton, the British sent two photographers to Crimea but neither of their work survived. One of them, Richard Nicklin, captured the war but he was lost at sea, along with his assistants, photographs, and gear, when their ship sank because of a hurricane.

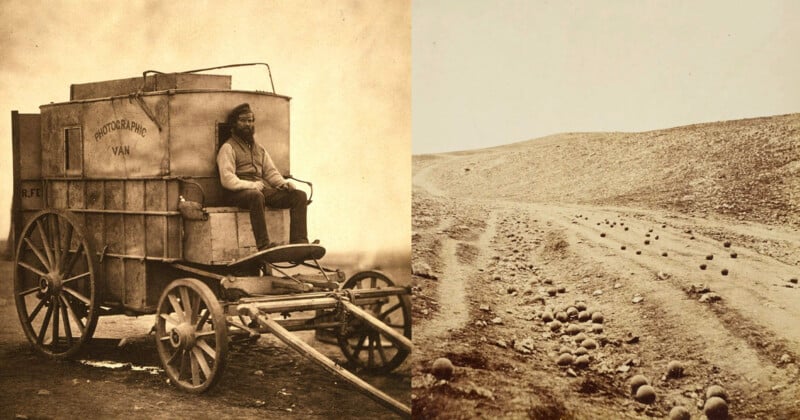

And so in February 1855, Fenton stepped up to this daunting and terrifying role as one of the world’s first war photographers and set sail to Crimea having purchased a wine merchant’s van to use as a mobile darkroom.

In the 1850s, photography was in its infancy and Fenton used a large format wet plate collodion camera, a standard technology of the mid-19th century. This method involved a labor-intensive process where a glass plate was coated with a collodion solution, sensitized with silver nitrate, and exposed in the camera while still wet. The equipment was cumbersome and required immediate on-site development, which Fenton accomplished using a horse-drawn mobile darkroom he brought to the Crimean War.

Fenton’s Raison D’etre

Quite what Fenton’s objectives were is a little murky. He traveled to Crimea under royal patronage and with the assistance of the British government. His trip was organized by William Agnew, a publisher who wanted to mitigate some of the negative press the war had been getting back home in England.

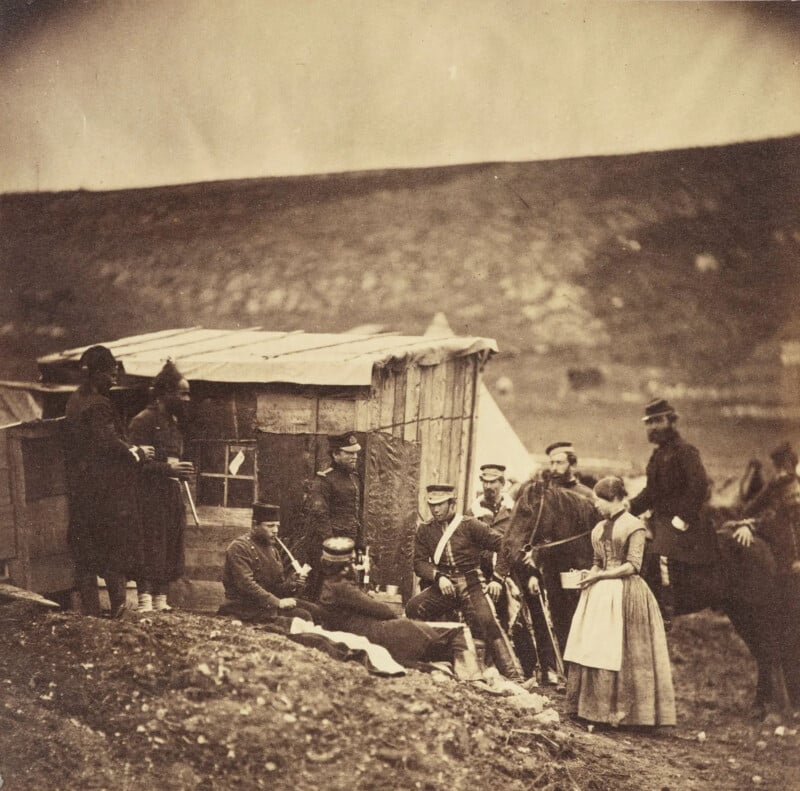

While Valley of the Shadow of Death suggests a brutal battle, Fenton did not document the full horrors of war that would have been all around him. The Crimean War, caused by geopolitical tensions, claimed the lives of nearly half a million people.

Granted, it was not easy to even take a picture in the 1850s. Long exposure times meant that action scenes were impossible and it was also extremely hot when Fenton was there; making his large format camera even more difficult to operate.

But ultimately, Fenton refrained from capturing anything too grisly which was either a pre-arranged deal with the British government and the publisher William Agnew. Or, it was just an implicit understanding between a member of the landed gentry and a government keen to keep negative images out of the public’s view.

Cholera and the End of the War

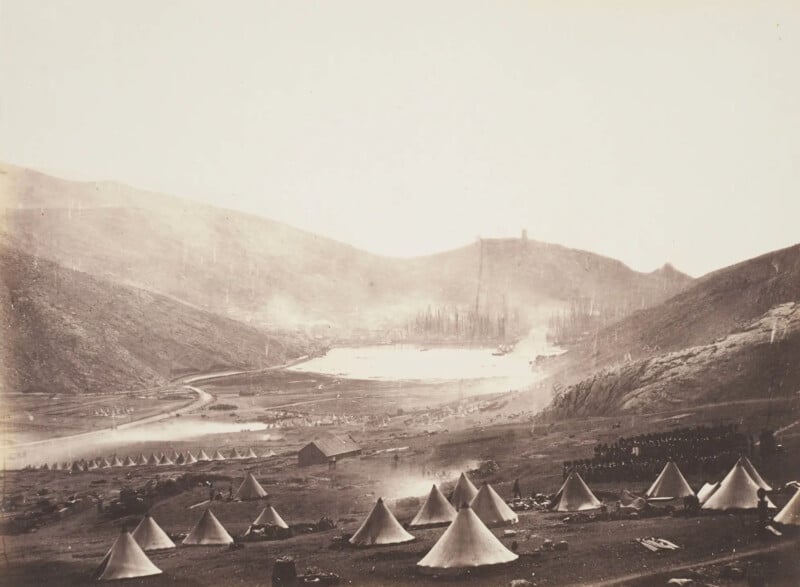

The main objective of the Ottoman, French, and British alliance was the destruction of Russia’s main naval base Sevastopol. Fenton had photographed the plateau in front of Sevastopol and intended to photograph the port following an assault in June 1855.

However, the assault failed and Fenton, suffering from cholera, decided to pack up his van and sail back to England. Sevastopol did eventually fall in September and was photographed by James Robertson.

Post-War

Although Fenton may have been one of the world’s first government propaganda photographers, his work was never exploited in this way. By the time his prints went on sale in November 1855, the public had lost interest or grown tired of the Crimean War which was now over thanks to the fall of Sevastopol.

William Agnew, the publisher, disposed of Denton’s unsold prints, and by 1862 Fenton had given up photography for good, selling off all his gear. He died in 1869 without knowing that his work would later be recognized by historians as important documents of the era.

Image credits: Photographs by Roger Fenton.