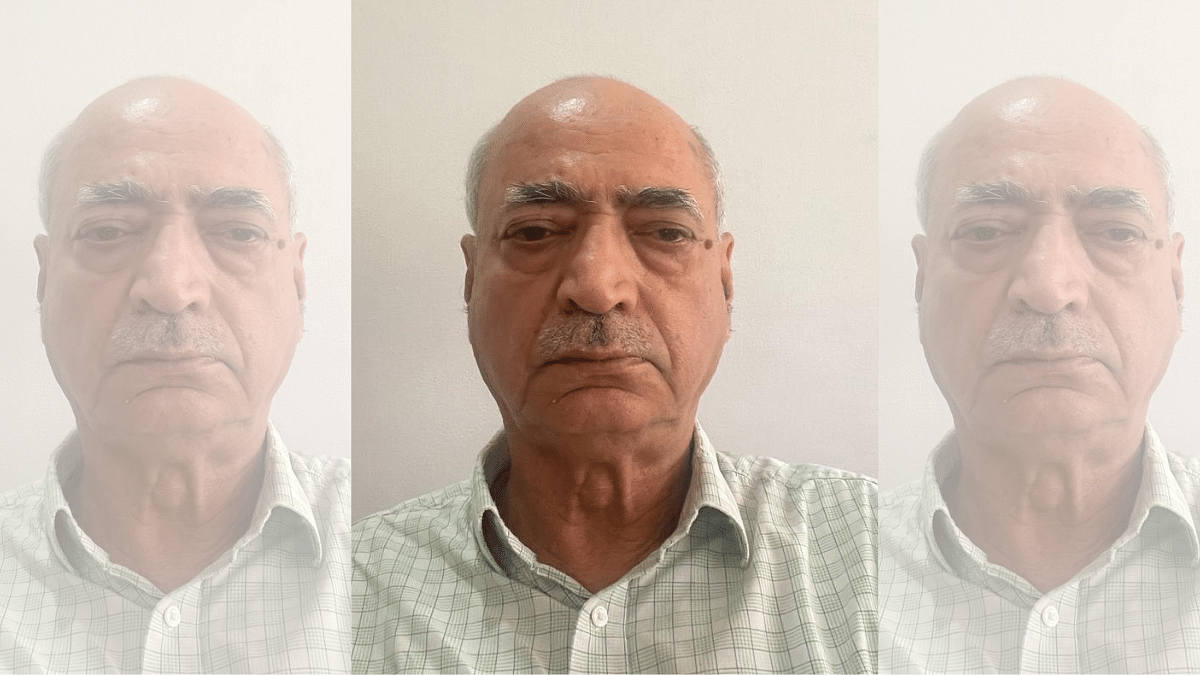

New Delhi: CSIR-National Institute of Oceanography former director Syed Wajih Ahmad Naqvi is one of the 13 recipients of the first Vigyan Shri awards for his contributions in the field of earth sciences.

With over five decades of research, the 70-year-old oceanographer’s work has delved into the complexities of oceanic water chemistry, biochemistry, and the intricate chemical interrelations with organisms.

Naqvi spoke to ThePrint about the significance of ocean studies in the context of climate change and India’s upcoming deep-ocean mission, Samudrayaan.

Below are the edited excerpts of the interview:

Could you tell us a little about your work in the field of ocean sciences and deep-sea studies?

I am an oceanographer pursuing research on the cycling of elements such as nitrogen, carbon and iron in the oceans. These elements play key roles in modulating biological production and atmospheric composition and, thereby, the climate of our planet. The cycles of these elements are biologically mediated. Also, as they occur in multiple oxidation elements, their cycles are strongly controlled by the ambient oxygen concentrations. Therefore, aquatic environments that experience oxygen deficiency are crucial for the biogeochemical cycles and global fluxes of these elements.

However, severe oxygen depletion is not very common in seawater, with natural-occurring anoxic conditions being restricted to just a few well-defined parts of the water column. Such conditions are widely found at mid-depths in the northern parts of the Indian Ocean (Arabian Sea, and Bay of Bengal). These areas, therefore, make disproportionate contributions to global biogeochemical cycles.

My research over the past five decades has been focused on these systems. As the biogeochemical processes of these so-called “oxygen minimum zones” are dominated by redox nitrogen processes, these processes, especially denitrification (conversion of nitrate to elemental nitrogen) and production and consumption of nitrous oxide (laughing gas), an important greenhouse molecule which is also an important contributor to the destruction of ozone in the stratosphere, have been the subject of my work.

India is working on a very ambitious deep-ocean mission, Samudrayaan. What would this exploration mission’s relevance be, and how significant would it be?

The oceans cover 71 percent of the Earth surface, but our knowledge about oceanographic processes still remains severely limited. For example, the seafloor contains hundreds of hydrothermal vents that support rich biodiversity and have unique food webs and energy sources. The first of these was only discovered eight years after man landed on the Moon (in 1969).

The Indian Ocean remains poorly explored for this purpose. Oceans are particularly important for India, which has a coastline exceeding 7,500 km and an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of more than 2.3 million km2 in area, in terms of living and non-living resources, environment and ecology/biodiversity, transportation and tourism and other economic benefits, and security.

The Samudrayaan was, therefore, conceived to explore the oceans around us and utilise its resources. Two of the main objectives of this initiative are—to understand oceanographic processes in our seas, and to develop advanced technologies to explore the ocean as well as to utilise its resources in a sustainable manner.

The emphasis should be on the preservation of the environment to minimise the magnitude of impending changes arising from human activities, while maximising the utilisation of its resources. Development for technologies for underwater use—such as a submersible capable of diving to 6 km depth and deep-sea mining—must be done indigenously. The need for underwater equipment for the security of the country cannot be overemphasised. Thus, the outcomes of the ongoing deep-sea mission will be highly significant.

Over the last few years, ocean warming and climate impacts have been a major concern for the Indian sub-continent. In such a scenario, how important does studying ocean sciences become?

Oceans play the primary role in making our planet habitable. Two important properties of water are—it has a very high specific heat (the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 gm of a substance by 1 degree Celsius), and, it is a universal solvent.

Because of the first characteristic, seawater is absorbing most of the extra heat being produced due the accumulation of greenhouse gases (mainly carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane) in the atmosphere. In fact, in the absence of this phenomenon, the air temperature would have risen by about 38oC over the modest warming that we are already experiencing. The increase of oceans’ heating content is, however, causing substantial warming, especially in surface waters. There are indications that our waters are being heated more than those in other areas.

Although the magnitude of this warming is under 1oC, it is already resulting in serious deleterious effects on climate (including the Indian monsoon), ocean circulation, ecology/biodiversity/living resources, elemental cycling, sea level, etc. As a consequence of the second characteristic, seawater absorbs as much as a quarter of all CO2 released by humans. Since CO2 is an acidic molecule, its uptake from the atmosphere leads to an increase of ocean acidity, with potentially largely implications for environment, climate, biogeochemistry/ecology/biodiversity and living resources.

Finally, the oceans also receive large amounts of pollutants including fertilisers and plastic waste. The former causes coastal water to become more productive, which together with physical changes is leading to expansion and intensification of oceanic oxygen-depleted zones, something that I personally work on. Plastic pollution has also become a very serious problem lately. There are also numerous other pollutants, both inorganic and organic, that are extremely harmful to the environment and biota, including human beings.

There was a lot of controversy last year when the government decided to do away with all the existing science awards and began this new category of ‘Vigyan Puraskar’. What are your thoughts about this move? And what do you have to say about receiving the first set of Vigyan Awards?

The government has reduced the total number of awards and changed the selection procedure. One can argue both in support of and against this decision, but being a policy issue, I will refrain from commenting on it. Having been selected for the award, I feel extremely elated and honoured, of course.

However, I wish to convey feedback received from some younger colleagues. Most of them were not very happy with the abolition of cash prizes as well as the research grants. Personally, I have received five cash prizes in my career, and I can say the money I received has been very helpful to my family.

For example, the money (Rs. 10,000) that accompanied a CSIR Young Scientist award in 1987 enabled me to buy our first colour TV. Those were relatively hard times. The salary structure has greatly improved since then, but I still think that younger scientists should also be given cash prizes or other benefits, particularly research grants.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: 1 yr of Chandrayaan-3: How the mission shaped India’s lunar exploration & what we know about the Moon