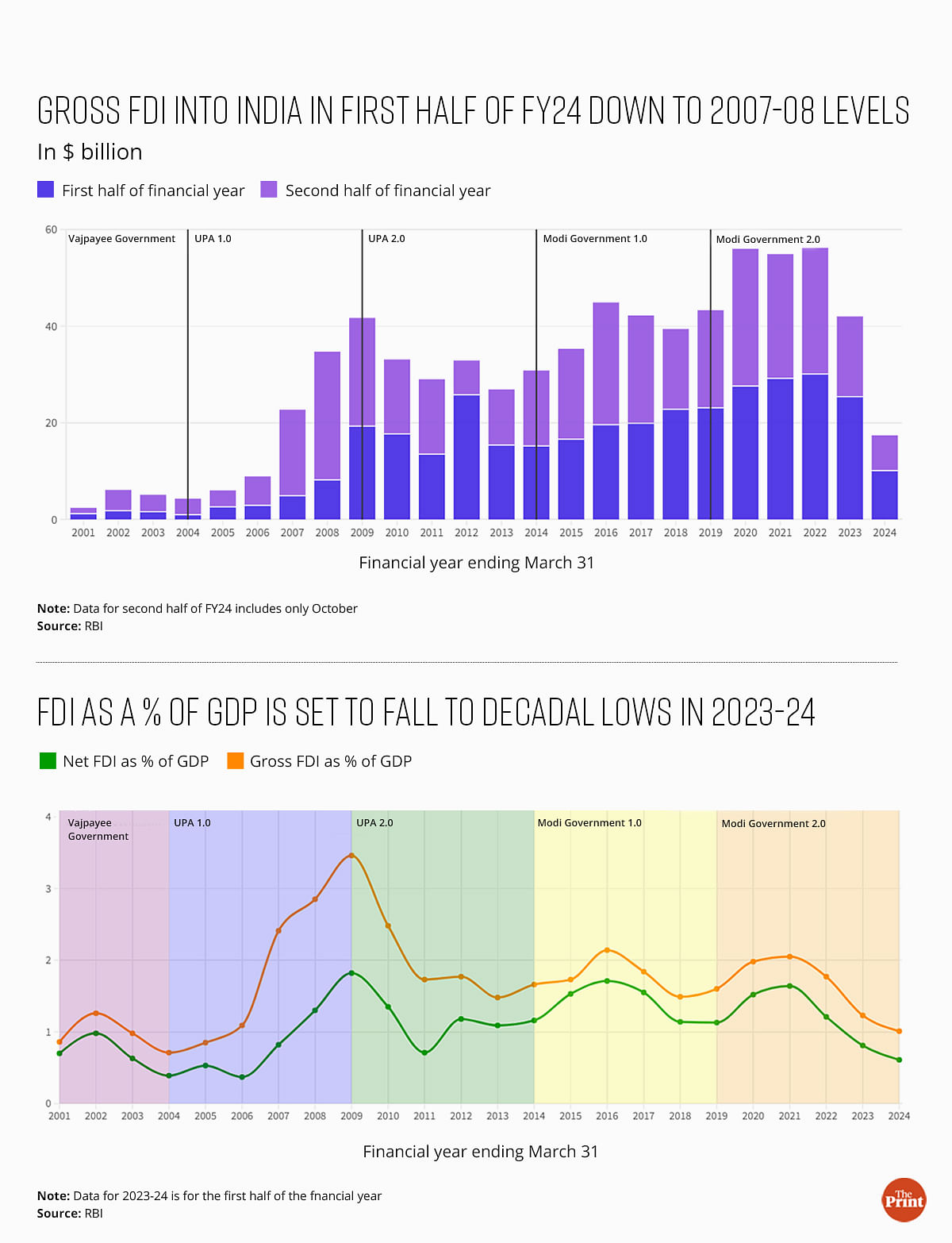

Similarly, as a percentage of India’s GDP, gross FDI flows dropped to just 1 percent in the first half of financial year 2023-24, while net FDI fell to 0.6 percent. These are levels last seen in 2005-06.

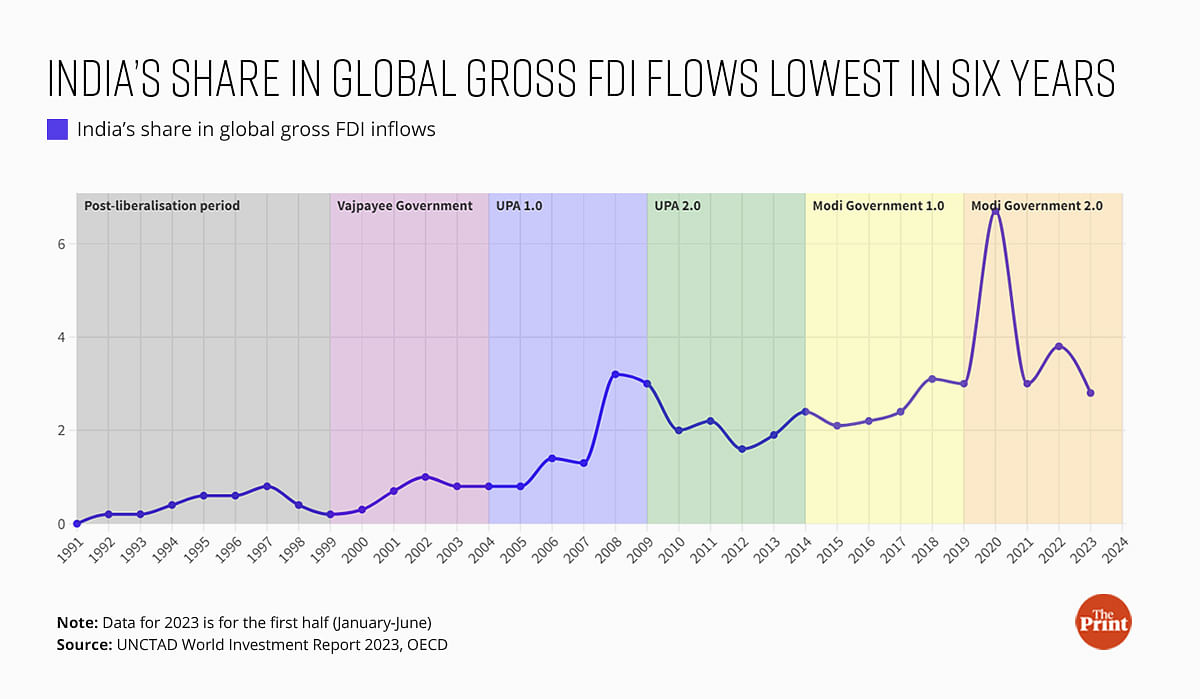

The government has argued in Parliament that this fall in FDI flowing into India is because of a global slowdown. However, the analysis shows that while global FDI inflows have indeed fallen — largely because investments have stopped flowing into China and have begun flowing out — India’s share in global FDI inflows has also been falling.

In other words, global FDI inflows have been falling and India is receiving a decreasing share of what remains. India’s share in global FDI inflows fell to 2.8 percent in the January-June 2023 period, the lowest since 2017.

Economists and investment analysts say the reason behind India’s lacklustre FDI inflows, which have largely fallen as a percentage of GDP since 2014, is down to the policies of the Modi government.

To begin with, despite improvements in India’s ranking on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index, actually doing business in India is still a difficult process impeded further by red tape.

The second major deterrent for foreign investors, they say, is India’s scrapping of all its Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs). This deprived foreign companies of any protection from judicial proceedings in India.

The third factor is India’s stated policies on Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). Having signed one with Australia and the UAE, New Delhi has been trying to finalise similar trade pacts with the EU, the UK, and the US. This, analysts say, would give companies in those countries access to Indian markets without them having to invest here.

Also Read: Income inequality reducing, one-third tax filers in bottom slab moved up to higher levels since 2014

Sharp fall in FDI in recent years

In absolute terms, gross FDI inflows to India amounted to $10.1 billion in the first half of this financial year, down 60 percent from the same period of the previous financial year, which itself was down 16 percent from the first half of FY 2021-22.

October 2023 did see a surge in FDI of $7.3 billion, but that still put the current financial year’s total well below that of preceding years.

While absolute figures provide some insight into the money coming into the country, the expectation is that, as the economy grows, so will the funds flowing into India. A look at FDI as a percentage of GDP shows whether this has actually been the case.

During the first term of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA), both gross FDI and net FDI shot up as a percentage of GDP — from 0.8 percent and 0.5 percent, respectively, in FY 2004-05 to 3.5 percent and 1.8 percent, respectively, in FY 2008-09.

Thereafter, it fell sharply again, perhaps in reaction to the global financial crisis in 2008-09. However, the UPA ended its 10 years in power with both gross and net FDI making up a higher percentage of GDP than when it came to power.

The Modi government has seen the opposite. Gross and net FDI as a percentage of GDP fell marginally over its first term, and the second term has seen both fall even faster.

“India’s FDI flow has been witnessing a declining trend,” Sumit Shekhar, an analyst at Delhi-based Ambit Capital said in a research note published this month. “A bigger concern is the rise in the share of reinvested earnings in net FDI inflows. This means the economy is struggling to attract newer investments as FDI in new equity grew by just 2.5 percent year-on-year in FY13-23 while reinvested earnings increased by 7 percent.”

He added that while FDI in services in India grew relatively strongly over the last decade, inflows into the manufacturing sector, led by sectors like automobiles and metallurgy, contracted.

Government policies to blame

While some of the recent slowdown in FDI in India could be explained due to what’s happening in the US, the longer trend of largely flat FDI over the last decade is due to a perceived lack of genuine ease of doing business, according to D.K. Srivastava, chief policy advisor at EY India.

“Recently, over the last year-and-a-half, the US interest rates were hiked and a lot of money was flowing back to the US,” Srivastava said. “But over the last decade, the reason for FDI not growing along with the economy is that genuine ease of doing business has not yet come in.”

“There are still a lot of constraints and rigidities and so investors are still reluctant to put their money in India,” he added.

Another major reason for India’s tepid FDI flows over the last decade has to do with India’s termination of the majority of its Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) — agreements between two countries that provide various protections to companies from one country investing in the other. One of these protections is that any arbitration or court case involving the company would take place in a third country, to eliminate any bias.

India had entered into BITs with 74 countries as of 2015, Minister of State (MoS) for External Affairs Rajkumar Ranjan Singh informed the Rajya Sabha in March 2023.

Of these 74, the government sent notices of termination to 68 countries and regions with a request to re-negotiate, while six BITs remain in force. After 2015, the Indian government signed four BITs, of which two are in force.

A June 2022 paper published in the peer-reviewed journal The Review of International Organizations found “a significant reduction in FDI inflows to India in response to BIT terminations by more than 30 percent compared to countries without terminations”.

“We identify the sudden break with investor protection for new investments as the major transmission channel,” the paper added.

Investment analysts agree with this assessment, saying that the terminations of BITs “majorly dented” investment flows into the country.

“When a company that doesn’t really know anything about India wants to invest here, it has fears about land acquisition, labour issues and various other things that can be taken to court,” an analyst from a leading research agency with its India headquarters in Mumbai, explained to ThePrint, on condition of anonymity.

“BITs used to provide that protection against court cases.”

“However, by terminating them, this government has removed those protections and the companies are no longer confident that they won’t be taken to an Indian court, the outcome of which is a foregone conclusion,” the analyst added.

The analyst also said that India’s eagerness to enter into FTAs signalled to companies around the world that they just had to wait for these agreements so that they get access to the Indian markets, without having to invest here.

India’s share in global FDI also falling

In December 2023, Minister of State (MoS) for Commerce and Industry Som Parkash told the Rajya Sabha that “FDI inflows have also been impacted by the threat of global recession, economic crisis due to Russia-Ukraine conflict, global protectionist measures and decline of real GDP growth rates of Singapore, USA and UK which are the major source countries for FDI”.

This assessment found many takers including Aditi Nayar, chief economist at the credit ratings agency ICRA, who said that India’s FDI situation needs to be looked at in the global context.

“The declining FDI flows to India aren’t surprising since this is in line with what’s happening globally,” Nayar told ThePrint.

“There appears to be an ongoing ‘funding winter’ in the startup sector. So, the factors driving this moderation in FDI are not specific to India.”

The data does show that India’s share in global FDI inflows has been largely increasing over the years, but it also shows that this share fell to just 2.8 percent in 2022-23, the lowest it has been since 2017.

“US investors are trying to shift away from China, but their preferred destinations are still Vietnam and South Korea and to some extent India, but here it’s only in some specific sectors of the economy,” Srivastava said, adding that “it is not broad-based”.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: From IMF to rating agencies, Modi govt’s rebuttals are improving. Backed by data & valid arguments