Back in the day, 35mm film was called “miniature” format; its itty bitty negatives were considered only good for snapshots and maybe street photography (sorry, Leica shooter Henri Cartier-Bresson). Serious photography—landscape, portraiture, documentary, commercial—was dominated by medium format film, a platform that produced images with fine detail and luscious tonality, even when blown up to make billboard-size prints.

By the late 1960s, medium format, used by legendary camera brands such as Rolleiflex, Hasselblad, and Zeiss Ikon, had been overtaken by 35mm as the preferred consumer film, but medium format never went away, and you can still shoot it; 120 film is readily available at photography retailers, priced about the same as 35mm emulsions.

Today, as film photography roars back to relevance, why bother with 35mm when you can go big—and enjoy the tactile, immersive experience of operating superbly built mechanical devices with manual settings? Digital photographers as well as film shooters can benefit from trying medium format; wrapping your fingers around a classic analog camera is a great way to practice the fundamentals of photography and the art of slow, mindful composition.

Bigger is Better

Why is it called medium format? Because cameras shooting 120 film occupy a middle ground between 35mm and large format, bulky cameras that expose 4×5-inch and 8×10-inch sheet film. In my view, medium format hits the sweet spot of film photography, combining outstanding image quality with ease of use and portability.

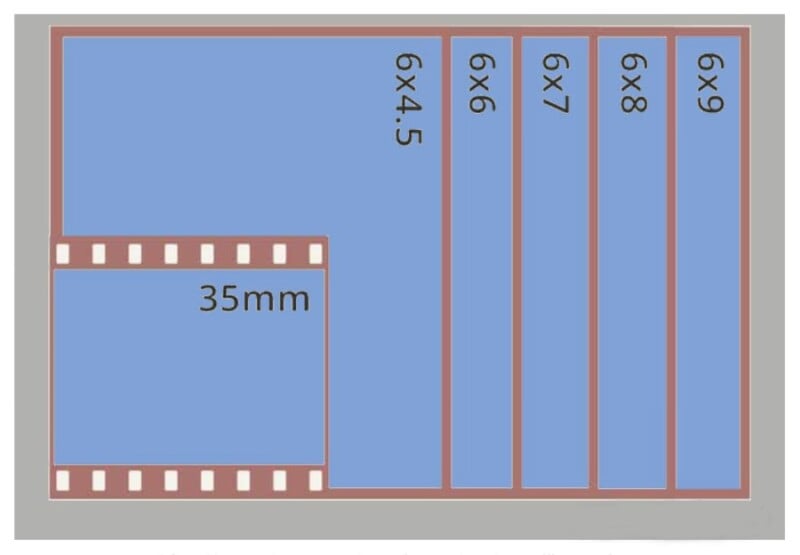

What’s immediately apparent about medium format is the size of the negative; depending on the camera used, it’s from two to six times larger than 35mm (see chart). These generous proportions yield images with remarkable clarity and depth; details are finer with less apparent grain, gradations in tonality more nuanced, colors more saturated. And because scans or prints needn’t be magnified as much, dust on the negative (the bane of the scanning process) is less noticeable.

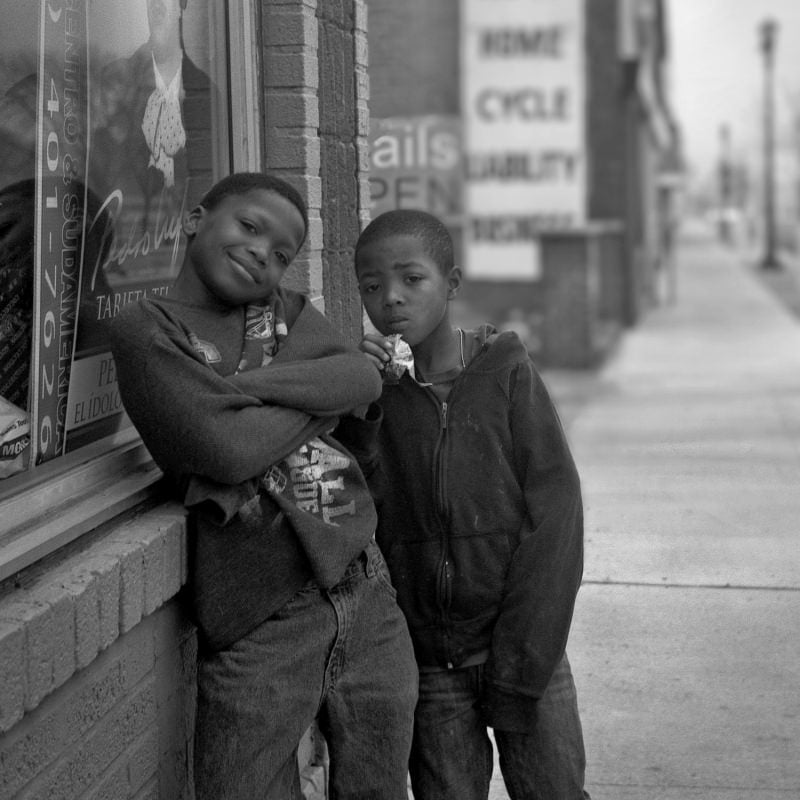

A big negative also means shallow depth of field, allowing for marked separation of foreground from background. The optics of a larger image format dictate lenses of longer focal length to capture the equivalent angle of view seen through a 35mm viewfinder. For example, a Hasselblad requires an 80mm lens to achieve roughly the same “normal” angle of view rendered by a 44mm lens on a 35mm or full-frame digital camera. The result: an out-of-focus background with alluring bokeh even at medium apertures—highly desirable for closeups and portraits such as this:

Narrow depth of field is a key element—along with fine detail and smooth tonality—of the distinctive “medium format look.”

Medium format cameras come in a variety of aspect ratios, from square to rectangles of different dimensions; most available today use 120 roll film, which is 6 centimeters (2¼ inches) wide. Common formats are 6×4.5 cm, or 645; 6×6 (a favorite of Ansel Adams) and 6×7. Less common are 6×8, 6×9—the same ratio as 35mm and many digital cameras—and various panoramic sizes up to a massive 6X17. The downside of medium format is fewer frames per roll than 35mm; shooting 645, you’ll only get 16 shots out of a roll of 120; 6×6 gives you 11 or 12; and 6×9 limits you to eight. There’s a consolation, however; each frame is all the more precious, fostering a deliberate, contemplative approach to image making.

The Joy of Medium Format

For me, medium format offers a more tangible, intimate, and rewarding shooting experience than shooting 35mm or digital. I’m particularly drawn to cameras made before 1980 with completely mechanical innards—no autofocus, no auto exposure modes, no menus. The process of manually advancing film, adjusting aperture and shutter speed, and focusing on the subject forges a deep connection with the craft of photography and gives me the mental space to fully evaluate the scene before pressing the shutter.

Some features of medium format cameras can take a while to get used to. One-twenty film must be carefully loaded in dim light because there’s no cassette to protect it from accidental exposure. Twin lens reflex (TLR) cameras like the Rolleiflex and Minolta Autocord have two lenses, one for taking the photo and a twin for viewing the image in a ground glass, top-mounted screen; you hold the camera at waist level and look down at a laterally reversed image to frame and focus the shot. Focusing classic rangefinders such as the Zeiss Ikon Super Ikonta C, pictured below, involves peering through a tiny eyepiece and turning a small knurled wheel attached to the lens to align a split image in the window.

And did I mention that older medium format cameras usually lack a built-in light meter (or if there is one, it’s probably as dead as Victor Hasselblad)? In that case, plan on using a handheld meter, a phone app, or the sunny 16 rule to gauge exposure.

However, many medium format cameras manufactured from the late ‘80s through the 2000s sport fully functional exposure meters, autofocus, auto and semi-auto shooting modes, a range of interchangeable lenses, and other features found in 35mm film cameras of the same era and modern digital cameras.

Finding a Medium Format Camera to Love

Chances are there’s a medium format camera out there suited to your preferred subjects and photographic style. Some cameras, such as the Mamiya 7 rangefinder and later Rolleiflex models, are pricey due to their advanced features or cult status, but many less coveted cameras cost $400 or less for a basic body-plus-lens setup. Below are my picks of cameras that offer a joyful shooting experience within the means of most photographers looking to expand their horizons to medium format. These models are generally available used on Etsy or eBay; if you’re lucky you may also find them at secondhand camera retailers, antique stores, or in your grandparents’ attic.

Pentax 645N. A thoroughly modern (for the 1990s) single lens reflex with autofocus, manual and automatic exposure modes with matrix metering, motor drive, and a full complement of high-quality yet affordable lenses. The camera, relatively small and light, for medium format, shoots 6×4.5 cm images, the same aspect ratio as Micro Four Thirds digital cameras. Priced at $250-$600 for body and lens.

Mamiya 645 series. A variety of models with electronic focal plane shutters, interchangeable viewfinders and focusing screens, and a deep lineup of lenses catering to diverse preferences and budgets. Later models have autofocus, onboard metering, and various degrees of auto exposure, but largely manually operated models made in the 1970s (M645, M645 1000 S) are renowned for their build quality and durability. Basic kids start at about $200.

Hasselblad 500 C/M. Hasselblad is one of the most revered camera brands in history, celebrated for its superb build, modular design (interchangeable viewfinders and film backs as well as lenses), and razor-sharp optics. Hasselblads flew with the Apollo astronauts to the moon. Like all Hassies, the 500 C/M is an SLR that takes square, 6×6 cm photos; it’s manual-everything—no autofocus, exposure modes, or light meter—making it one of the most affordable models out there: A decent body with lens runs $800 to $1,500.

Mamiya C330. The C330 was popular with wedding photographers in the 1970s; I shoot landscapes and portraits with mine. This angular chunk of a camera captures square photos, and alone among TLRs, uses interchangeable lenses. The sharp Sekor 80mm lens comes standard; Mamiya also manufactured 55mm, 65mm, 105mm, 180mm, and (hard to find) 250mm lenses for the camera. Expect to pay around $250-$300 for a copy in good condition.

Zeiss Ikon Super Ikonta. Steampunk elegance meets engineering precision in the Super Ikonta line of rangefinders made by Zeiss Ikon from the 1930s through the ‘50s. Super Ikontas are iconic folding cameras: press a button and the lens and bellows—yes, bellows—spring out of the body, ready for action. Folded, the camera is small enough to slip into a coat pocket. The Super Ikonta “A” shoots 645 images; the “B” model 6×6, and the “C” 6x9mm. Cameras in working order start at $200.

Holga 120N. A fun, easy-to-use, and incredibly cheap (in build quality and price) camera that shoots 6×6 images. Holgas are called toy cameras because they’re almost entirely made of plastic, with rudimentary aperture and focus settings (shutter speed is fixed at roughly 1/100th of a second). But artists and hipsters love them for the dreamy, surrealistic images they produce, thanks to light leaks and optical idiosyncrasies. Perfect for street photography—nobody will take you seriously. Pick one up new for less than $50.

Now you have no excuse not to shoot medium format film. Go big and have fun!

About the author: Phil Davies is a writer and landscape photographer based in St. Paul, Minnesota. Visit his website to see more of his work. Davies’ travel book Scenic Driving Minnesota (Globe Pequot Press) is slated for publication this summer.