While the final agreement at the conference was passed with no changes from attending parties, including India, its call to “transition away” from fossil fuels does raise questions about India’s capability to do so. For starters, India does not plan to decommission (shut down) any coal power plants until 2030, and has coal-based power plants with a generation capacity of 27 gigawatts (GW) in various stages of implementation currently, according to a response given by the government in Lok Sabha this month.

The COP28 final agreement mentions the phasedown of coal as a separate clause. It calls for “accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power”, which has been a clause highly debated by the Indian and Chinese delegates for the last two UN climate conferences.

India is the second largest producer of coal in the world, after China. In 2022, India accounted for 11 percent of the world’s total coal produced.

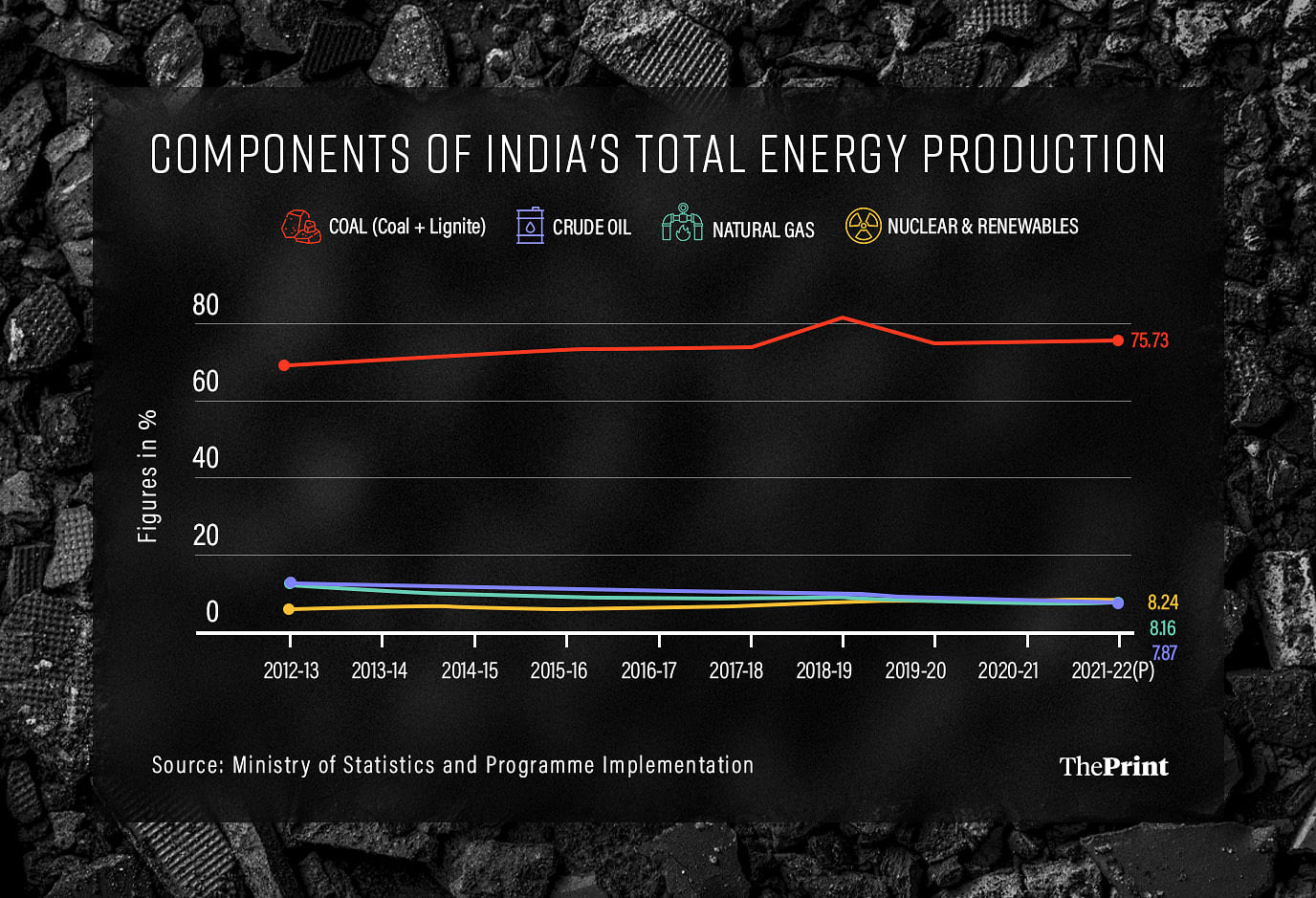

More importantly, coal accounts for more than half of India’s energy needs. Historically, coal has contributed around 75 percent of the total energy generated in India, with other sources of energy only serving the country’s energy needs at the margins.

“Coal-based electricity is still the cheapest source of baseload power when solar/wind generation tapers. For a stable supply of electricity at affordable prices, we need coal,” Utkarsh Patel of the Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP) told ThePrint.

Also read: Expect fewer power cuts this summer as govt ensures enough coal supply to power plants

India’s coal dependence

Coal power forms a major chunk of India’s energy generation capacity.

As of May 2023, the total energy generation capacity from fossil fuel sources such as coal, gas, and oil was 56 percent, while it was 43 percent from non-fossil fuel sources. Of this 56 percent, coal accounted for 49 percent of the production capacity. Currently, India has more coal-based, or thermal, power production capacity than all other renewable energy sources combined.

But generation capacity is distinct from the energy actually generated from these sources.

While coal plants make up 49 percent of the installed power production capacity in the country, they accounted for an overwhelming 75 percent of the total energy production in 2021-22, the latest year for which there is data with the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

The use of crude oil and natural gas, the other fossil fuels, have reduced in the last two years due to increasingly expensive imports.

Renewable energy production, including that of nuclear power, has not yet crossed the 10 percent of total production mark.

As recently as October 2022, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman had said in a conference that India “would be forced to use more coal as gas prices increase”. She was referring to the impact of the Russia-Ukraine war, which has increased natural gas prices, making it expensive to import.

According to experts, India’s focus on coal is also for purposes of energy security. India is significantly dependent on imports for its natural gas and crude oil power plants. Increasing coal production capacity in the country is a way to secure our energy needs.

“We would like to rely on domestic resources for our energy production so that geopolitical shifts don’t throw off our balance,” says Vibhuti Garg, South Asia director, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

Even government officials have been quoted in the media as saying that energy security is more important than climate goals for India.

Some experts point out the difficulty of development without fossil fuels.

“Every economy in the world developed by using cheap fossil fuel energy, but India is expected to develop without it?” asks Saurabh Kumar, the Vice President of Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet (GEAPP).

Coal demand is even higher

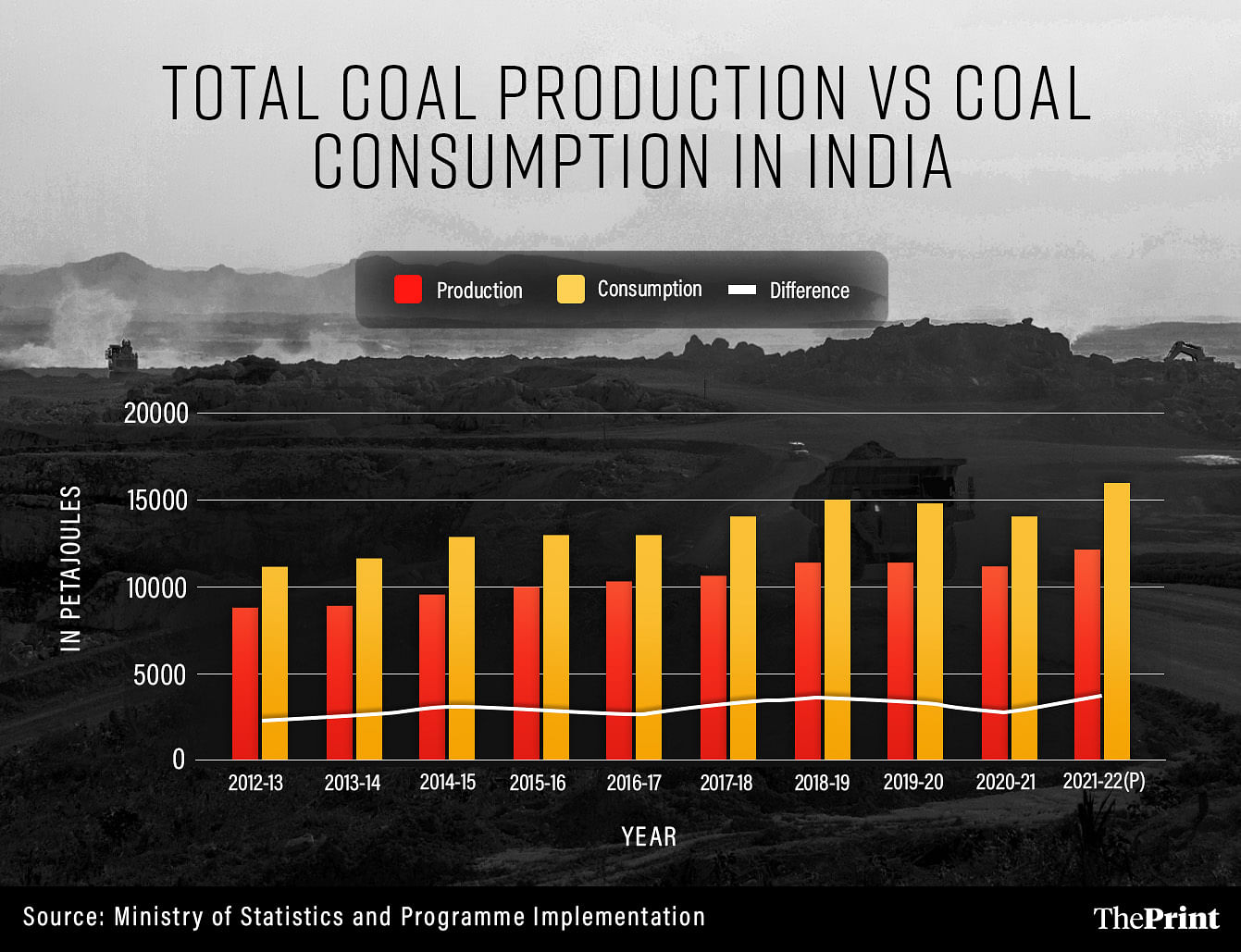

Available data further shows that despite India’s high share of coal production, it still cannot match the domestic demand for coal.

The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation’s (MoSPI’s) Energy Statistics India Report 2023 shows India’s coal demand has consistently been higher than its coal production in the past decade.

The difference between coal production and demand is usually met with coal imports. According to the Ministry of Coal website, coal is freely imported into the country under the Open General License.

“India has not even reached its peak coal demand yet,” said Garg.

This means that the current role coal plays in India’s energy mix is expected to increase further before it can decrease to augment the process of “transitioning away” from fossil fuels.

The country is expected to reach its peak coal demand sometime between 2030-2035, according to a Ministry of Coal’s communication in 2022.

India’s nationally determined commitments at COP26 was to achieve 50 percent total energy capacity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. However, the increase in renewable energy capacity does not necessitate a decrease in fossil fuel capacity.

The Minister of Power and New & Renewable Energy, R.K. Singh, said in a Lok Sabha reply on 14 December that the total energy requirement in the country has increased by 9.6 percent from 2019 to 2023.

In line with the increasing demand, the minister explained that 20 new thermal power plants are coming up in the country, with a total capacity of 27,180 megawatts (MW). Coal already has the highest power production capacity of 2,05,235 MW in the country, of all other sources.

So, along with hydro, wind, and solar capacity, coal capacity is also set to increase.

Phasing out fossil fuels, especially coal, must also be done in a just manner, Patel noted.

“The livelihoods of millions of people in India depend directly or indirectly on the coal supply chain. Any plan to phase out coal must address this issue in a fair manner,” he said.

Problems with phaseout

The phaseout or transition away from fossil fuels to clean energy also needs to take into account the costs of renewable energy storage, production, and transmission.

A 2022 report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) showed how equipment and material costs for renewable energy globally have increased. Most countries, including India, saw an increase in the prices of solar photovoltaic modules and wind turbines used to generate energy from renewable resources.

This was exacerbated by supply chain issues, said the report, owing to the lingering effects of the Covid pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. Other issues include the variable nature of renewable energy sources.

“Renewable energy is intermittent,” said Patel. “Building energy storage systems like grid-scale batteries and pumped hydro plants to store renewable energy for later use is currently very expensive.”

Garg further said that the current investment in coal power plants might be a good way to combat the high energy demand in the country and problems with renewable energy storage, but is “a long-term solution for a short-term problem”.

She pointed out that coal power plants are long-term investments, and the problems of renewable energy storage and peak energy demand might be solved in the next few years.

“For coal power plants, you’re looking at a 25-year-long investment, sometimes even more,” said Garg.

She also warned that with the global push for renewable energy in this decade, our coal plants might soon become stranded assets. Stranded assets are those that are no longer functional and become a liability to the economy.

A better solution, according to Garg, would be to deploy investment toward renewable energy sources including solar, nuclear, and green hydrogen.

Patel too believes India should define its goal with regard to phasing out of coal.

“We need to chart out a plan explicating the expansion, peaking, and phase-down of coal capacity,” urged Patel. “Such a plan should specify the date after which no new coal power plants would be approved for construction, and also a date by which we expect coal power generation to peak.”

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Coal is railways’ cash cow — why India’s climate goals pose risk for transporter