Patna: The Bihar socio-economic survey, tabled in the assembly by the Nitish Kumar government on 7 November, has shown that 9.98 percent of the Hindu ‘upper-caste’ population has migrated out of the state, contrary to popular belief that largely associates outward migration with the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs).

In comparison, the migration of OBCs from the state is pegged at 5.39 percent and of EBCs at 3.9 percent.

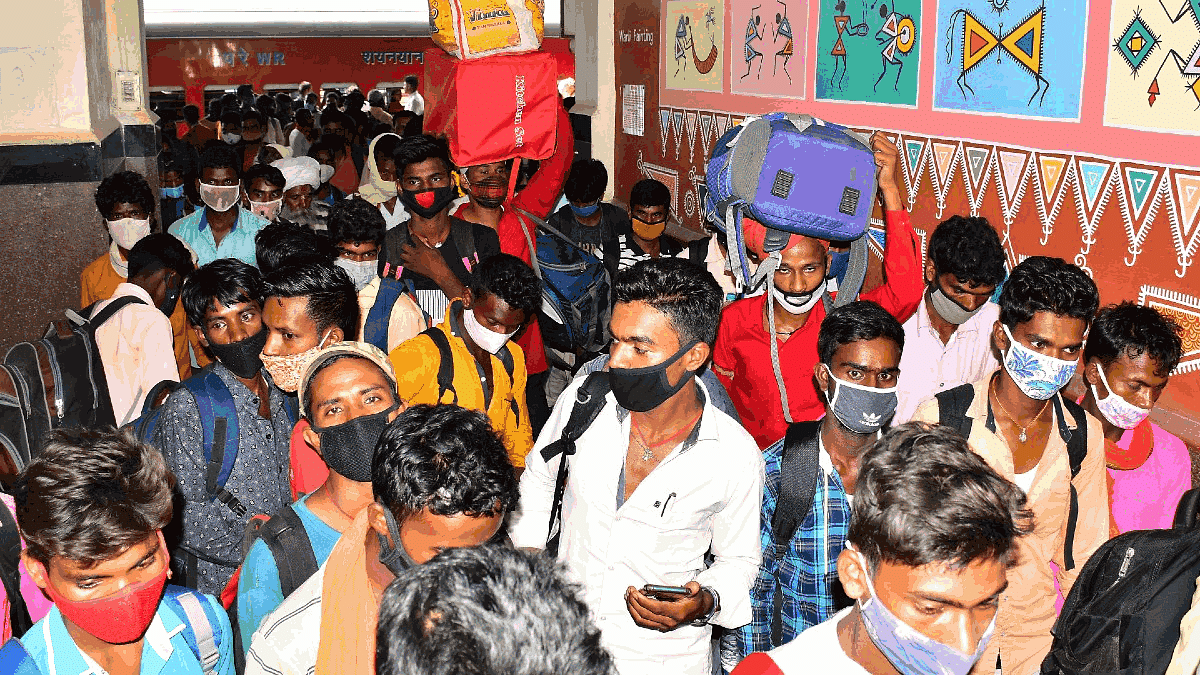

For the Bihar caste survey, a door-to-door survey was conducted and if it was found that a person or persons had migrated, within or outside the state, it was recorded using a structured format.

Migration by the ‘upper’ castes isn’t a new phenomenon and can be attributed to many factors. While in the early 1990s, they left the state to escape Maoist violence, lack of entrepreneurial spirit and fear of social stigma have also contributed to driving them out, said experts.

However, such migration has a political fallout. The upper castes have been Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) voters for the past three decades. The caste survey shows that upper castes — Brahmins, Rajputs, Kayasthas and Bhumihars — constitute about 10 percent of the population.

Bhumihars are an upper-caste Hindu community found mainly in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

“With the exodus of ‘upper’ castes and thus, most of them not returning to vote, their voting power is depleting. It’s natural for most parties to search for votes outside the ‘upper’ castes,” said a senior BJP leader.

Also read: Nitish’s ‘special category status’ demand for Bihar raises BJP hackles — ‘why not ask in 5yrs in NDA’?

Lack of education, jobs

Education and employment opportunities initially drove the ‘upper’ castes out of the state, said experts. “The ‘upper’ castes are traditionally better educated classes. When higher education began to collapse in the 1970s, most of the ‘upper’ castes moved out — first for higher education and then for jobs as Bihar had nothing to offer to them,” said Dr Ashesh Dasgupta, a former professor of sociology at Patna University.

In the 1970s, the student-led Bihar movement, also known as the JP (Jayaprakash Narayan) movement, against the Congress government in the state, had resulted in universities and colleges becoming hot beds for political activities.

Dasgupta added that the need for higher education saw migration pick up among OBCs and EBCs too.

Former Jehanabad MP Arun Kumar recalled the “turbulent 1990s”, which saw caste tensions and Maoist violence at their peak, as a period when ‘upper’ castes migrated in droves.

Jehanabad was the epicentre of this turbulence, he said. The Bhumihars, the dominant caste there, left Jehanabad following much carnage.

A visit to Bhumihar-dominated villages in Jehanabad makes this evident. In these villages, many houses are characterised by heavy locks on their doors.

“About 30 percent of the houses are still locked,” said Kumar, adding that though the cycle of violence has ended, many residents have not returned. “Those who were doing menial jobs, such as working in a hotel in Kolkata or being a guard in an apartment building, came back. But those who did better financially by opening shops and starting ventures in Pune, Mumbai and other parts of the country, did not return. The story holds good for all Maoist-hit areas of Bihar.”

He alleged collusion between the administration and the Maoists against the upper castes, and said that the latter’s migration from Bihar increased after Lalu Prasad Yadav began to occupy centrestage.

However, not all agree with him. Politicians alone aren’t to blame for ‘upper’-caste migration, said Dr Shefali Roy, professor of political science, Patna University. “Caste has been there right from the days of the first CM. There is so much bitterness among castes in academics and administration that the youth wanted out, so they left the state. It’s more prevalent among the ‘upper’-caste youth as there is a sense of insecurity (that they would face discrimination in finding jobs because of reservation),” she said, adding that lack of entrepreneurial spirit has also contributed to the exodus.

Also, social stigma deters an ‘upper-caste’ person from engaging in non-traditional occupations in their area. So, if someone is forced to work as a labourer, they would rather do it in another state that offers them anonymity.

“A Brahmin or any (other) upper caste will not work in the fields, drive a tractor or work as guards due to social stigma. But outside the state, they will do it. There is a social taboo which is still strong,” said N.K. Choudhary, a former professor of economics at Patna University.

(Edited by Smriti Sinha)

Also read: CM Nitish apologises for ‘vulgar’ statement on population control. BJP targets his age, ‘mental health’